Anglo-Saxon

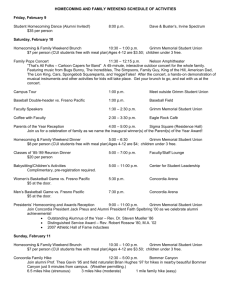

advertisement

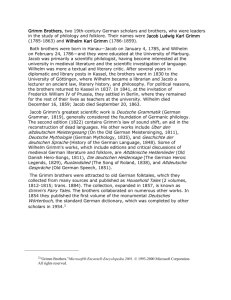

Lecture 1 Studying Modern English we find in its vocabulary, phonetic & grammar systems such phenomena which seem incomprehensible from p/v of Modern language. In the vocabulary field considerable generality between English & German: summer, Sommer (Germ); winter, Winter; foot, Fuᵝ; long, lang; sing, singen; sit, sitzen. On the other hand between English & French: autumn, automne; river, riviere; modest, modeste; change, changer; condemn, condamner etc. The reasons for these correspondences c.b. found in a >/< faraway past. In the field of relationship between pronunciation & spelling: why ~ light, naught, know, gnat etc. – some letters are written which aren’t pronounced? ~ speak, great, bear, heard, heart – different pronunciation? ~ sun, cut, butter – [ᴧ] is defined by the letter u but in love, son, brother – by the letter o? In the Grammar field: why ~ man, foot, goose, mouse – Sg. men geese, feet, mice – Pl. ? ~ sheep, deer – Sg., Pl.? Both these cases differ from the general rule of the ending s. ~ can, may, will differing from the general rule have no ending in the 3 rd P., Sg., Pres.? All these cases date back to some period of the English language development & can’t be explained without its studying. That’s why knowledge of the History of the English language is part & parcel of theoretical preparation of the qualified teacher of English. Proto-Germanic consonant shift. Grimm’s Law The German word J.Grimm uses, “Regel,” means “rule,” and could just as easily mean “correspondence.” It is also worth noting that Grimm could find no way of including the vowels in his scheme and did not have much luck with the liquids (r, l). Grimm began with the assumption that had been in place since the time of Jones, that Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and other European languages—most importantly those in the Germanic branch—had a common ancestor. This common ancestor, which, following contemporary practice rather than Grimm’s own, we will call Proto- Indo-European, could be reconstructed by examining its descendants. E.g., we examine the words for “father” and “foot” in a variety of Indo-European languages: Sanskrit Latin Ancient Greek English pitar pater patếr father pad ped pῡs foot Because the “p” sound appears in a wider variety of languages, it is assumed to be ancestral and the “f” in English to be derived from a consonant shift. Grimm concluded that the ancestral forms were p, t, k, b, d, g, bh, dh, and gh (the “h” represents aspiration). They shifted, in the Germanic languages, in the following manner: p→f t → th k→h b→p d→t g→k bh → b dh → d gh → g So the I part of Grimm’s Law is the following: The voiceless stops in Proto-Indo-European became voiceless fricatives in Germanic. the II part of Grimm’s Law is the following: The voiced stops in Proto-Indo-European become voiceless stops in Germanic. the III part of Grimm’s Law is the following: The voiced, aspirated stops become voiced, un-aspirated stops. Grimm’s Law is so important not only because it demonstrated that there was logical regularity underlying language change, but also because it allowed researchers to reconstruct the lost Indo-European language. Exceptions Explained, Verner’s Law Grimm’s Law had remarkable explanatory power, but there were exceptions to it that were not easily explained. This did not bother Grimm himself, who accepted the idea that there were exceptions to his rules, but subsequent linguists were determined to figure out additional regularities. The most successful was the Danish linguist, Karl Verner (1846–1896), who in 1875 formulated Verner’s Law. Verner examined words in which p did not become f, t did not become th, and k did not become h in the shift from Proto-Indo-European to Germanic. Thus in Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek, as well as Baltic and Slavic languages, there were words that included p in which the cognates in Germanic languages also had p, rather than f. For example, the p in the Proto-Indo-European word for father does indeed become an f, as Grimm’s Law would predict. But in Proto-Germanic the word is “fæder,” with a “d” rather than the “th” we would expect from Grimm’s Law. Even more confusing, the Proto-IndoEuropean word for “brother” does follow Grimm’s Law, with the Proto-Germanic form being “brother” rather than “broder.” Verner studied these words very carefully and noted a correspondence: When the vowels before the p, t, or k (the unvoiced stops) were unstressed, Grimm’s Law did not come into effect. In Proto-Indo-European, the stress was on the second syllable of “father” (compare the Sanskrit pit-á ) while it was on the first syllable of “brother” (Sanskrit bhrá-ta). One reason it had taken so long for linguists to figure out Verner’s Law was that somewhat later in the development of the Germanic languages stress had become fixed on the root syllable of a word (this had not been the case in Proto-Indo- European or Proto-Germanic). The voicing occurred in PG at the time when the stress was not yet fixed on the root-morpheme. unstressed vowel + voiceless stop → voiceless fricative →voiced fricative → voiced stop: /t/ → /þ/ → /ð/ → /d/. According to Verner’s Law voiceless fricatives /f/, /þ/, /h/ which arose under Grimm’s Law, and also /s/ inherited from PIE, became voiced between vowels if the preceding vowel was unstressed; in the absence of these conditions they remained voiceless. The consonant pairs involved in grammatical alternation were f/b, þ/d, h/g, hw/w, s/r. The sound /z/ was further affected in western and northern Germanic: /s/→/z/→/r/. This process is known as rhotacism. As a result of voicing by Verner’s Law an interchange of consonants in the grammatical forms of the word appeared. Part of the forms retained a voiceless fricative, while other forms – with a different position of stress in Early PG – acquired a voiced fricative: wesan (быть) – wæs (был) – wæron (были); weorþan (становиться) – wearþ (стал) – wurdon (стали) – worden (превращенный). Both consonants could undergo later changes in the OG languages, but the original difference between them goes back to the time of movable word stress and PG voicing. Vowels of GLs: GLs also had some specific features in the system of vowels. IE short /ŏ/ and /ǎ/ correspond to GLs short /ǎ/: Gr octō – Goth ahtau, Rus ночь – Germ nacht IE long /ō/ and long /ā/ correspond to GLs long /ō/: Lat frāter – Goth brōþar (брат), Lat flōs – OE blōma (цветок). Short /ŏ/ & long /ā/ appeared in GLs from inner sources. Germanic fracture: In GLs the quality of a stressed vowel in some cases depended on the type of the sound that followed it. This dependence is reflected in the notion of fracture. The fracture concerns two pairs of vowels: /e/ & /i/, /u/ & /o/. In the root syllable IE /e/ = GL /i/, if it was followed by 1) /i/ 2) /j/ 3) nasal+consonant, else IE /e/ = G /e/. Examples: Lat medius – OE middle, Lat ventus – OE wind but Lat edere – OE etan. IE /u/ = GL /u/ if followed by 1) /u/ 2) nasal+consonant, else IE /u/ = G /o/. Example: Lat sunus – OE sunu (сын) (pp. 35- 41 История а/я Т.А.Расторгуева) Old English. Historical background There are 3 distinctly marked stages in the history of the English language: Old English (OE), or Anglo-Saxon, Middle English (ME) & Modern English (MnE), or New English (NE), within which Present Day English (PDE) is distinguished. The OE period dating from the 1-st coming of the Germanic tribes to the British Isles in the 5th c. & lasting till 1100, is a period of comparatively rich grammatical inflections — a period of full endings. (Detailed periodisation of the History of English — p.54 История а/я Т.А.Расторгуева) Pre-Anglo-Saxon Britain was inhabited by the Celtic tribes called Picts, Scots, and Britons (hence “Briton”, and “British” referring to the people of the whole of the British Isles). In 43 A.D. the major part of the island became Roman as the Emperor Claudius finally brought Britain into the Empire. Unable to conquer the Scottish Highlands and a province of Britain in the south, the Romans seized what is known as the Midlands and the south-east, where they built their towns and roads, bringing along their way of life. The Roman rule continued in Britain up to the 5thс. A.D., when the Roman legions withdrew, leaving the colonists and romanized natives unprotected in face of the threat of the attacks of the continental Germanic tribes. In the middle of the 5th c. the Germanic invaders started their conquest of Britain. The barbarians and the colonists, who came a few years later, belonged to West Germanic peoples: the Saxons, Angles, Frisians and Jutes. The traditional idea that Kent was inhabited by Jutes has not been backed up by archeological evidence. There are more arguments in favour of the fact that the settlers in Kent came from various tribes. Lack of the word “Jute” in geographical names is another factor that makes the presence of Jutes in Britain doubtful (J.M. Williams). The tribal groupings settled in seven Alnglo-Saxon kingdoms. Apart from Kent, they were Wessex - the land of West Saxons, Essex - the land of East Saxons, Sussex - the land of South Saxons; farther north three Anglian kingdoms: Northumbria (north of the river Humber), Mercia (between the Thames and the Humber), and East Anglia (in the central part of Britain). The romanized Celts were either destroyed or driven into the woods and mountains. Only Wales, Cornwall and Scotland remained Celtic. The conquerors called the Celts WEALH (> Welsh), which meant “foreigners” as they could not understand the Celtic language, that, in spite of being Indo- European, was vastly different from their own. To this day the descendents of the ancient Celts live on the territory of the British Isles. The Welsh who live in Wales are of Celtic origin. They speak Welsh, a Celtic tongue. In the Highlands of Scotland as well as in the western parts of Ireland there are also people who speak Gaelic, which is also Celtic by its origin. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms — Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Kent, Wessex, Essex, and Sussex — were constantly struggling for leadership, and in the 7th c. it passed from Kent to Northumbria, known for its monasteries in which the first libraries and schools were set up and translates and chroniclers were educated. The most famous writer was the monk Bede (c. 673735), the first English historian, known in Europe as the Venerable Bede, His “Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum” (“Ecclesiastical History of the English People”) written about . 731 supplies the traditional account of the Anglo-Saxon intervention to Britain. In a wave of migrations which extended over a large part of the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. people from northern continental Europe brought to the British Isles a language of a kind which had previously been unknown there. These migrants appear to have come from a number of different places. They spoke a range of dialects and in their new home they each encountered and interacted with speakers of other varieties of their own language, as well as with people speaking quite different languages, namely the Celtic languages of the native British population, and the form of Latin which many of those people seem to have used under the recently ended Roman governance of Britain. As these migrants (whom we call the Anglo-Saxons) started their new and separate life in the British Isles, their language began to develop in its own distinctive ways and to become different from the language of their previous neighbours on the Continent. It was also exposed to influences from the indigenous Celtic languages and from Latin. But the Anglo-Saxons were never completely isolated, and trade and other activities continued to keep them in contact with people across the channel and the North Sea. The Anglo-Saxons and the Scandinavians The Viking raids began in 793 in Northumbria where the Scandinavians destroyed the church at Lindisfame which had been built by the Scottish monk Aidan to convert the Northumbrians to Celtic Christianity (635-651). That is how the pagan Scandinavians extinguished the light of learning in the north of England. The Danes soon occupied the north-western part of the country established permanent settlements there. This region became known as the Danelaw, an area, in which the Danes were free to have their own mode of life. Thus the country was divided into two parts: the Danelaw and the English south-western part which was under king Alfred’s rule. Having united at least half of England, Alfred, as noted above, embarked on creating a prose tradition by his various translations from Latin into Old English, which are believed to have been done by himself and at his direction by others. He also founded the first public schools, creating a literate audience for the literature as well as an educated class to govern the growing state. In fact, Alfred organized Anglo-Saxon government so well that the Danes in their Danelaw who were less organized than the English were finally unable to withstand the unified political and military attacks by Alfred’s son, Edward the Elder (c. 870-924), and his son, Athelstan (c. 895-940). In 957, Edward’s grandson, Edgar (944-975) became ruler over Northumbria and Mercia and undertook an attempt to unify the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. For his peacemaking policy he became known as the Peaceful King. In 975 he was recognized an overlord of Britain. At the end of the 10th c. new Danish raids broke out, particularly during the reign of king’s Edgar’s successor, Ethelred the Redeless (c. 968-1016), who got such a name because he did not take anybody’s counsel (OE read). Being a rather incompetent ruler he tried to buy the Danes off. Realising that he was a failure he fled away through the Channel to Normandy to his wife’s relatives. After Ethelred’s death, Saxon and Danish England engaged in a brief civil war before Cnut (c. 994-1035), a Dane, defeated Wessex in 1015. He and Edmund Ironside (c. 9801016), Ethelred’s son, divided the island between them, and when Edmund died in 1016, Cnut became the king of the entire kingdom. He was also the king of Denmark and Norway. He made England the centre of his power, which enabled the Danish businessmen and traders to get an easy access to southern England, particularly London. Danish merchants became a significant part of the leading tradesmen and citizens. Supported by the Anglo- Saxon feudal lords Cnut ruled in England till he died. The Danes established a second Danelaw on the northern coast of Franc which was part of the Frankish kingdom. In the 10th c. they founds dukedom of Normandy (the toponeme originating from the name of the conquerors – Normans, or Northmen), from which their romanized descendants attacked England a century later. Closer to the end of Cnut’s rule, the son of Ethelred the Redeless and Emma, daughter of Richard the Fearless, duke of Normandy, Edward the Confessor (c. 1002-1066), who was strongly influenced by the Norman clergy and more interested in being a monk than a king, returned to England. In 1042 he ascended the throne. The Impact of the Danelaw on the Anglo-Saxon The Danes did not essentially differ from the English among whom they lived, because they were also of Germanic origin and their level of culture was not greatly different. They were far fewer in number, which brought about their racial assimilation. The 135 years of the Danelaw could not but tell upon the English language. The actual need to communicate led to intermixture of Old English and Old Norse (Old Scandinavian). As the two languages belonged to the same linguistic group their speakers could easily understand each other. Phonetic influence of Old Norse on the Anglo-Saxon language was practically imperceptible. In morphology the impact of Old Norse was very important because it was one of the causes serving to reduce the system of Old English inflections. There being a lot of cognates among the words employed in Anglo-Danish intercourse, the interlocutors made their roots particularly valid and their inflections practically inconspicuous. Apart from the weakening and reduction of grammatical endings Old Norse brought about several changes in pronominal systems. The Scandinavian borrowings they, them, their ousted the Old English 3rd p. p1. forms, which were homonymous with the singular. SAME, borrowed from Scandinavian, replenished the system of demonstratives. In wordstock Scandinavian borrowings were rather numerous. Such commonly used nouns as fellow, husband, law, window, leg, wing, sky, skill, skirt, as well as adjectives happy, wrong, low, loose, ugly, weak, and verbs call, cast, take, die, skip, droop are of Scandinavian origin. A lot of place names in the region where the Scandinavian settlers used to live were the elements pertaining to Old Norse: by “village” (Derby, Grimsby), toft “grassy spot”, “hill” (Lowestoft, Langtoft), beck “rivulet” (Troutbeck); ness “cape” (Inverness, Caithness). Old English writing & written records Runic inscriptions – p.63 История а/я Т.А.Расторгуева Most of the extant Old English manuscripts were written in Wessex during the reign of King Alfred, who came to the throne in 871 and died in 899. His activities in education, learning and administration created cultural golden age in Wessex. To king Alfred’s first literary works belongs the translation of Pope Gregory’s “Cura Pastoralis” (“Pastoral Care”), to which he added a preface, accounting for the decay of learning in Britan and containing his determination to reform the schools in Wessex. Along with this original contribution to Old English literature Alfred the Great did the translation of the “Seven Books of History against the Heathens” written in the 5th c. by the Spanish monk Paulus Orosius and treated as a standard text book of universal history. The most important literary figure, who also wrote in Wessex was iElfric, Abbot of Eynsham, (955-1020). He composed his “Catholic Homilies” and “Lives of the Saints” and also translated “A Latin Grammar”, supplying it with a preface of his own, and the “Colloquium” (a manual containing dialogues to be used at monastic schools). Wulfstan, another master of Late Old English prose, who was Archbishop of York in the early 11th c., created a collection of sermons, the best of which “Sermo Lupi ad Anglos” reveals the problems facing the Anglo-Saxons at that time. Alfred is not only the founder of a prose tradition but also an initiator of the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicles”, recording the events annually at various monasteries.A lot of legal documents were written in Wessex as well as in other Old English dialects. They are laws of the Anglo-Saxon kings, various agreements grants, wills, records of proceedings of church councils which are commonly known under the general heading of the “Anglo-Saxon Charters”. The first examples of Old English poetry occurred as insertions in Latin texts. Bede’s “Death Song” and “Caedmon Hymn” make part of the Alfredian translation of Bede’s “Ecclesiastical History of the English people”. “Beowulf”, a poem of 3183 lines, has been preserved practically complete in a manuscript of the 10th c. It is believed to have been originally composed in a dialect of the north or Midlands of England in approximate 680, though it has survived in the West Saxon form. The Northumbrian dialect has got down to the present day not only in various runic inscriptions, but also in the texts of the Ruthwell Cross and Franks Casket, and a translation of the gospels. The Mercian and Kentish dialects are preserved in charters, psalters, hymns and glosses, which are separate words or interlinear word-for-word translations written between the lines of Latin manuscripts made for the benefit of those who had a poor knowledge of Latin.