Missouri State-Bess-Rumbaugh-Aff-NDT

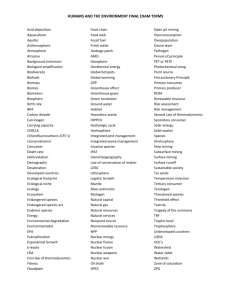

advertisement