Cinematic Techniques

advertisement

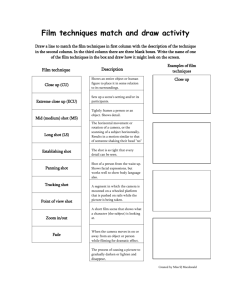

Cinematic Techniques Cinematic techniques are methods employed by film makers to communicate meaning, entertain, and to produce a particular emotional or psychological response in an audience Lighting technique and aesthetics In film making, the use of light can influence the meaning of a shot. For example, film makers often portray villains that are heavily shadowed or veiled, using silhouette. The background light is used to illuminate the background area of a set. The background light will also provide separation between the subject and the background. In the standard 4point lighting setup, the background light is placed last and is usually placed directly behind the subject and pointed at the background. In film, the background light is usually of lower intensity. More than one light could be used to light uniformly a background or alternatively to highlight points of interest. In video and television, the background light is usually of similar intensity to the key light because video cameras are less capable of handling high-contrast ratios. In order to provide much needed separation between subject and background, the background light will have a color filter, blue for example, which will make the foreground pop up. Cameo lighting in film is a spotlight that accentuates a single person in a scene. It creates an 'angelic' shot, such as one where God is shining down and a light shines down onto this person. A lens flare is often deliberately used to invoke a sense of drama. A lens flare is also useful when added to an artificial or modified image composition because it adds a sense of realism, implying that the image is an un-edited original photograph of a "real life" scene. Mood Lighting : Light is necessary to create an image exposure on a frame of film or on a digital target (CCD, etc). The art of lighting for cinematography goes far beyond basic exposure, however, into the essence of visual storytelling. Lighting contributes considerably to the emotional response an audience has watching a motion picture. The control of light quality, color, direction and intensity is a major factor in the art and science of cinematography. Colours & Filters Filters, such as diffusion filters or coloreffect filters, are also widely used to enhance mood or dramatic effects. Most photographic filters are made up of two pieces of optical glass glued together with some form of image or light manipulation material between the glass. In the case of color filters, there is often a translucent color medium pressed between two planes of optical glass. Color filters work by blocking out certain color wavelengths of light from reaching the film. With color film, this works very intuitively wherein a blue filter will cut down on the passage of red, orange and yellow light and create a blue tint on the film. Certain cinematographers, such as Christopher Doyle, are well known for their innovative use of filters. Filters can be used in front of the lens or, in some cases, behind the lens for different effects. Mise en Scene : Props & Set Stemming from the theater, the French term mise en scène literally means "putting on stage." When applied to the cinema, mise en scène refers to everything that appears before the camera and its arrangement – sets, props, actors, costumes, and lighting. Mise en scène also includes the positioning and movement of actors on the set, which is called blocking. Cinematography & Camera Angles Cinematographic techniques such as the choice of shot, and camera movement, can greatly influence the structure and meaning of a film. The use of different shot sizes can influence the meaning which an audience will interpret. The size of the subject in frame depends on two things: the distance the camera is away from the subject and the focal length of the camera lens. Extreme close-up: Focuses on a single facial feature, such as lips and eyes. Close-up: May be used to show tension. Medium shot: Often used, but considered bad practice by many directors, as it often denies setting establishment and is generally less effective than the Close-up. Long shot: typically shows the entire object or human figure and is usually intended to place it in some relation to its surroundings; however, it is not as far away as an would be. Establishing shot: Mainly used at a new location to give the audience a sense of locality. Choice of shot size is also directly related to the size of the final display screen the audience will see. A Long shot has much more dramatic power on a large theater screen, whereas the same shot would be powerless on a small TV or computer screen. Camera angles These are used extensively to communicate meaning and emotion about characters: Low angle shot: Looking up at a character or object, often to instill fear or awe in the audience; Straight angle shot: Looking at an eye-level angle to a character or object, giving a sense of equality between subject and audience; High angle shot: Looking down on a character, often to show vulnerability or weakness; Canted or Oblique: The camera is tilted to show the scene at an angle. This is used extensively in the horror and science fiction genre. The audience will often not consciously realize the change. This is most often referred to as a 'dutch' angle, or 'going dutch'. The most obvious and frequently referenced use of this technique is found in the 'Batman' TV show and original movie (when the villains were on screen, the camera would show them at a canted angle). Sound Sound is used extensively in filmmaking to enhance presentation, and is distinguished into diegetic ("actual sound"), and non-diegetic sound: Diegetic sound: It is any sound where the source is visible on the screen, or is implied to be present by the action of the film: Voices of characters; Sounds made by objects in the story; and Music, represented as coming from instruments in the story space. Music coming from reproduction devices such as record players, radios, tape players etc. Non-diegetic sound: Also called "commentary sound," it is sound which is represented as coming from a source outside the story space, ie. its source is neither visible on the screen, nor has been implied to be present in the action: Narrator's commentary; Voice of God; Sound effect which is added for dramatic effect; Basic sound effects, e.g. dog barking, car passing; Mood music; and Film Score Non-diegetic sound plays a big role in creating atmosphere and mood within a film. Sound effects In motion picture and television production, a sound effect is a sound recorded and presented to make a specific storytelling or creative point, without the use of dialogue or music. The term often refers to a process, applied to a recording, without necessarily referring to the recording itself. In professional motion picture and television production, the segregations between recordings of dialogue, music, and sound effects can be quite distinct, and it is important to understand that in such contexts, dialogue and music recordings are never referred to as sound effects, though the processes applied to them, such as reverberation or flanging, often are. Special FX The illusions used in the film, television, and entertainment industries to simulate the imagined events in a story are traditionally called special effects (a.k.a. SFX or SPFX). In modern films, special effects are usually used to alter previously-filmed elements by adding, removing or enhancing objects within the scene. The use of special effects is more common in big-budget films, but affordable animation and compositing software enables even amateur filmmakers to create professional-looking effects. Special effects are traditionally divided into the categories of scenery effects and mechanical effects. In recent years, a greater distinction between special effects and visual effects has been recognized, with "visual effects" referring to postproduction and optical effects, and "special effects" referring to on-set mechanical effects. Optical effects (also called visual or photographic effects), are techniques in which images or film frames are created and manipulated for film and video. Optical effects are produced photographically, either "in-camera" using multiple exposure, mattes, or the Schüfftan process, or in post-production processes using an optical printer or video editing software. An optical effect might be used to place actors or sets against a different background, or make an animal appear to talk. Mechanical effects (also called practical or physical effects), are usually accomplished during the live-action shooting. This includes the use of mechanized props, scenery and scale models, and pyrotechnics. Making a car appear to drive by itself, or blowing up a building are examples of mechanical effects. Mechanical effects are often incorporated into set design and makeup. For example, a set may be built with break-away doors or walls, or prosthetic makeup can be used to make an actor look like a monster. Since the 1990s, computer generated imagery (CGI) has come to the forefront of special effects technologies. CGI gives film-makers greater control, and allows many effects to be accomplished more safely and convincingly -- and even, as technology marches on, at lower cost. As a result, many optical and mechanical effects techniques have been superseded by CGI. Editing Film editing is an art of storytelling practiced by connecting two or more shots together to form a sequence, and the subsequent connecting of sequences to form an entire movie. Film editing is the only art that is unique to cinema and which separates filmmaking from all other art forms that preceded it (such as photography, theater, dance, writing, and directing). However there are close parallels to the editing process in other art forms such as poetry or novel writing. It is often referred to as the "invisible art," since when it is well-practiced, the viewer becomes so engaged that he or she is not even aware of the work of the editor. Because almost every motion picture, television show, and TV commercial is shot with one camera, every single shot is separated from every other single shot by time and space. On its most fundamental level, film editing is the art, technique, and practice of assembling these shots into a coherent whole. However, the job of an editor isn’t merely to mechanically put pieces of a film together, nor is it to just cut off the film slates, nor is it merely to edit dialogue scenes. A film editor works with the layers of images, the story, the music, the rhythm, the pace, shapes the actors' performances, "redirecting" and often re-writing the film during the editing process, honing the infinite possibilities of the juxtaposition of small snippets of film into a creative, coherent, cohesive whole. Film editing is an art that can be used in diverse ways. It can create sensually provocative montages. It can be a laboratory for experimental cinema. It can bring out the emotional truth in an actor's performance. It can create a point of view on otherwise obtuse events. It can guide the telling and pace of a story. It can create the illusion of danger where there is none, surprise when we least expect it, and a vital subconscious emotional connection to viewer.