1ar – aff good

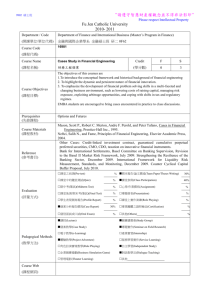

advertisement