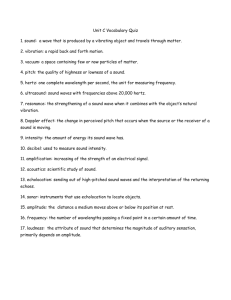

Fund_Acoustics

advertisement

Fundamentals of Acoustics

The Nature of a Sound Event

Sound consists of vibrations of air molecules

Air molecules are analogous to tiny superballs

Sound occurs when air molecules are disturbed

and made to ricochet off of each other

The Nature of a Sound Event

The ricochets cause the density of the air

molecules to oscillate

Rarefied

Normal

Compressed

The Nature of a Sound Event

The ricochets cause the density of the air

molecules to oscillate back and forth

ª›•Œ QuickTimeý ©M

°ßGIF°®

—¿£¡Yµ{¶°

®”¿Àµ¯

ošœµe°C

Wave Types

Sound consists of longitudinal waves

ª›•Œ QuickTimeý ©M

propagation

°ßGIF°®

—¿£¡Yµ{¶°

®”¿Àµ¯

ošœµe°C

oscillation

The wave’s

oscillation is in

the same

direction as its

propagation

Water waves are transverse waves

ª›•Œ QuickTimeý ©M

propagation

°ßGIF°®

—¿£¡Yµ{¶°

®”¿Àµ¯

ošœµe°C

oscillation

The wave’s

oscillation is

perpendicular to

the direction of its

propagation

Sound

Propagation

Sound waves

propagate in a sphere

from the sound

source (try to imagine

a spherical slinky).

Note that the

molecules themselves

are not travelling.

What spreads is the

energy of the wave.

ª›•Œ QuickTimeý ©M

°ßGIF°®

—¿£¡Yµ{¶°

®”¿Àµ¯

ošœµe°C

Sound Perception

Speed of sound (in air):

1128 ft./sec (344 m/sec)

When sound waves reach the eardrum, they

are transduced into mechanical energy in

the middle ear

The mechanical motion is transduced into

electrical current in the inner ear. The

auditory nerves interpret the current as

sound

Sound Wave Plots

Sound waves are typically represented with

molecular density as a function of time

compressed

normal

time

rarefied

molecular density

Music vs. Noise

Musical sounds are typically periodic – the wave repeats regularly

repeats

Sine wave

Though they don’t exist in

nature, sine waves are often

useful for demonstrating

properties of sounds

Noise is aperiodic – there is no repeating pattern

Noise

Properties of a Musical Event

A musical event can be described by four properties.

Each can be described subjectively, or objectively (in

terms of measured properties)

Subjective

Pitch

Objective

Frequency

Volume

Amplitude/Power/Intensity

Timbre

Overtone content

Duration in beats

Duration in time

Frequency/Pitch

Frequency is measured in cycles per second, or Hertz (Hz)

f = 2 Hz

Wavelength (l), the

distance between

corresponding points

on the wave, is the

inverse of frequency.

l =

c

f

=

1000 ft./sec.

2 cyc./sec.

one second

l

=

500 ft./cyc.

Frequency/Pitch

Middle A = 440 Hz

l = 2.3 ft.

20 Hz

l = 50 ft.

<

frequencies

audible to

humans

< 20,000 Hz (20 kHz)

l = 0.05 ft.

Sound wavelengths are significantly larger than light wavelengths

Waves reflect from a surface if its

height/width is larger than the wavelength

Waves refract around surface if the

surface dimensions are smaller than

the wavelength

This explains why we can hear sound from around corners,

but cannot see around corners:

Light wavelengths are far too small to refract around any

visible surface

Our Pitch Perception is

Logarithmic

Equivalent pitch intervals are perceived according to an

equivalent change in exponent, not in absolute frequency

For example, we hear an equivalent pitch class with every

doubling of frequency (the interval of an octave)

Frequencies of successive octaves of concert A

55

110

220

440

880

1760

3520

55 x 2 0

55 x 2 1

55 x 2 2

55 x 2 3

55 x 2 4

55 x 2 5

55 x 2 6

Our Pitch System is Based on

Equal Division of the Octave

12 Tone Equal Temperament –

the octave is divided into twelve equal increments

We can describe an octave by:

• choosing a starting frequency

n/12

• multiply it by 2

for n = 0 to 11

A

220

0

x 212

220

A#

220

1

x 212

233

B

220

2

x 212

247

C

220

3

x 212

261.6

C#

220

4

x 212

277

D

220

5

x 212

293.6

D#

220

6

x 212

311

E

220

7

x 212

329.6

F

220

8

x 212

349.2

F#

220

9

x 212

370

G

220

10

x 212

392

Higher octaves may be created by doubling each frequency

Lower octaves may be created by halving each frequency

G#

220

11

x 212

415.3

Phase

Phase = “the position of a wave at a certain time”

If two waveforms at the same frequency do

not have simultaneous zero-crossings, we say

they are “out of phase”

Wave 1 + Wave 2

Wave 1

Wave 2

Two waves at the

same frequency but

different phase

In terms of sound perception, phase can be critical or imperceptible,

as we’ll see...

Loudness

Loudness is related to three measurements:

• Power

• Pressure

• Intensity

All three are related to changes in sound

pressure level (molecular density)

Molecular Motion is Stationary

As sound travels, molecules are not traveling with

the sound wave

What is traveling is an expanding sphere of energy

that displaces molecules as it passes over them

How strong is the force behind this energy wave?

The more force is contained in a sound wave, the

greater its perceived loudness.

Power

Power = the amount of time it takes to do work

(exert force, move something)

Power is measured in watts, W

There are two difficulties in measuring sound power levels.

The range of human hearing encompasses many millions of watts.

Sound power level is also relative, not absolute. Air

molecules are never completely motionless.

Given these two difficulties, sound power levels are

measured on a scale that is comparative and logarithmic,

the decibel scale.

Logarithmic Scale

Logarithm = exponent

(an exponent is typically an integer, a logarithm not necessarily)

102 = 100

103 = 1000

log10100 = 2

log101000 = 3

102.698 = 500

log10500 = 2.698

102.875 = 750

log10750 = 2.875

Logarithms allow us to use a small range of

numbers to describe a large range of numbers

The Decibel Scale

The decibel scale is a comparison of a

sound’s power level with a threshold level

(the lowest audible power level of a sine

tone at 1 kHz).

Threshold (W0):

W0 = 10-12 watts

Power level of a given sound in watts, LW(dB):

L W (dB) = 10*log10 (W/W0 )

Decibels

Typical power levels:

Soft rustling leaves

Normal conversation

Construction site

Threshold of pain

10 dB

60 dB

110 dB

125 dB

Halving or doubling sound power level results in a change of

3 dB.

For example, a doubling of the threshold level may be

calculated:

410 12

LW(dB) = 10log10

10log10 2 3.01 dB

12

210

Thus, a power level of 13 dB is twice that of 10 dB. A

power level of 60 dB is half that of 63 dB, and so on.

Pressure changes

The degree of fluctuation present in a vibrating object

Peak pressure level:

Maximum change in sound pressure level

(more generally: in a vibrating system, the

maximum displacement from equilibrium position)

The amplitude level fluctuates with the wave’s oscillation.

Thus, power is the cause, pressure change is the result

Pressure changes

Also may be described as changes in sound pressure level

(molecular density).

Pressure level is measured in Newtons per square meter (N/m 2 )

-5

Threshold: 2 x 10 N/m2 (p0 )

There is a direct relationship between pressure and power

levels:

For any propagating wave (mechanical, electric, acoustic, etc.)

the energy contained in the wave is proportional to the square

of its pressure change.

Pressure changes are also expressed in decibels, but in a way

that describes an equivalent change in power level:

L W (dB) = 10*log10(W/W0) = 10*log10(p/p0)2 = 20*log10(p/p0)

logmn = nlogm

This is how pressure is

measured

Pressure changes

In audio parlance, “amplitude” (the degree of

pressure change) is often equated with “loudness.”

The reason is that modifications to volume are made by

adjusting the amplitude of electrical current sent to an

amplifier.

But perceived loudness is actually based on power level plus

the distance of the listener from the source.

Intensity

Power corresponds to the sphere of energy expanding

outward from the sound source

The power remains constant, spread evenly over the

surface of the sphere

Perceived loudness depends primarily on the sound

power level and the distance from the sound event

Power combined with distance is intensity, I,

measured in watts per square meter (W/m2 ).

Intensity is also measured in decibels:

L I (dB) = 10*log 10(I/I 0 )

-12

I0 = 10

W/m 2

Timbre

The perceived difference in sound quality when two

different instruments play at the same pitch and loudness

Sine waves are useful as demonstrations because they are a

wave with one frequency only, thus they are often termed

pure tones

Natural sounds are composed of multiple frequencies

To understand how a wave can be composed of multiple

frequencies, we can consider the behavior of a wave in a

bounded medium, such as a string secured at both ends (or

air vibrating within a pipe)

Timbre

When we pluck a string, we initiate wave motion

The wavelength is twice the length of the string

The perceived pitch is the fundamental, the speed

of sound divided by the wavelength

Timbre

This curved shape represents the

string’s maximum deviation

It’s more accurate to think of it as a

series of suspended masses (kind of like

popcorn strung together to hang on a

Christmas tree).

Timbre

Each suspended mass can vibrate independently.

Thus, many simultaneous vibrations/frequencies

occur along a string.

When a string is first plucked, it produces a

potentially infinite number of frequencies.

Timbre

Eventually, the bounded nature of the string confines wave

propagation and the frequencies it can support

Only frequencies that remain in phase after one propagation

back and forth can be maintained; all other frequencies are

cancelled out

Only frequencies based on integer subdivisions of the string’s

length, corresponding to integer multiples of the fundamental,

can continue to propagate

Timbre

These frequencies are called harmonics

NOTE:

These frequencies are

equally spaced

Therefore, they do

not all produce the

same pitch as the

fundamental

Therefore, other

frequencies are

introduced

…etc.

Timbre

Harmonics are well known to many

instrumentalists

–

–

Strings

Brass

Timbre

The first six harmonics are often the

strongest:

220

440

660

880

1100

1320

Fundamental

Octave

Perfect fifth

Octave

Major third

Perfect fifth

People can learn to “hear out” harmonics

Timbre

Instruments and natural sounds usually

contain many frequencies above the

fundamental

These additional frequencies, as part of the

total sound, are termed partials

The first partial is the fundamental

Timbre

The first partial is the fundamental

Other terms are also used

Overtones are partials above the

fundamental (the first overtone is the

second partial)

Harmonics are partials that are integer

multiples of the fundamental

The Spectrum

Jean Baptiste Fourier (1768-1830) discovered a

fundamental tenet of wave theory

All periodic waves are composed of a series of

sinusoidal waves

These waves are harmonics of the fundamental

Each harmonic has its own amplitude and phase

The decomposition of a complex wave into its

harmonic components, its spectrum, is known as a

Fourier analysis

The Spectrum

It is often more useful to represent complex

waveforms with a spectral plot as opposed to a time

domain plot

=

time domain

spectral domain

amplitude as a function of time

amplitude as a function of frequency

Sound in Time

Our perception of sound and music events is

determined by the behavior of frequency

and loudness over time

Sound in Time

All instruments can be characterized by

changes in amplitude over time (the

envelope)

loudness

trumpet

bowed violin

harp

Changes in amplitude often correspond with changes in

frequency content...

time

Sound in Time

Most instrument’s sound begins with an initial

transient, or attack, portion

The transient is characterized by many high

frequencies and noise

Example: the scraping of a bow or the chiff of

breath

An instrument’s distinctiveness is determined

primarily by the transient portion of its sound

Sound in Time

Following the transient, instruments usually

produce a steady-state, or sustained, sound

The steady state is characterized by

–

–

Periodicity

Harmonic spectrum

The Spectrogram

Most natural sounds (and musical instruments) do not

have a stable spectrum.

Rather, their frequency content changes with time.

The spectrogram is a three-dimensional plot:

Vibraphone note at 293 Hz (middle D)

2) frequency

3) power of a given frequency (darkness level)

1) time

The instrument’s sound is characterized by the fundamental at 293 Hz and the fourth harmonic at 1173 Hz.

The attack also contains noise below 2 kHz, the tenth harmonic at 2933 Hz and the seventeenth harmonic at 4986 Hz.

Once the steady state portion sets in, the highest harmonic fades first, followed by a fading of the fundamental.

Localization

The auditory system localizes events through

interaural time delay – the sound wave reaches the

nearer ear a few milliseconds before it reaches the

farther ear

For stereo systems, using delay for localization is

impractical because it requires people to listen

from a “sweet spot”

Localization effects are simulated through

differences in loudness

Localization

In a multi-speaker system, a sound emanating

from one speaker will be localized at that speaker

A sound produced at equal volume from two

speakers will be perceived as a “phantom image”

placed in space between them

Changing the volume balance between two

speakers will cause the phantom image to “drift”

towards the louder speaker

Measurement and Perception

Our perception of auditory events is based

on all these measurements in combination

And more

An auditory event may be more than the

sum of its parts

Measurement and Perception

Phase

Changing the phase of components in a steadystate tone produces no perceptible change in

sound, although the shape of the wave may change

noticeably

Measurement and Perception

Phase

The behavior of components in the attack segment is likely

to be far more complex than in the steady state segment

Changing the phase of attack components can change the

character of the attack

Solo performance sounds different from group

performance because no two players can ever sound at

exactly the same time; thus the attack is blurred

Since an instrument’s characteristics are defined primarily

by the attack, the phase of attack components is critical

Measurement and Perception

Timbre

We have discussed timbre as the result of overtone content

It is also judged by the sound’s envelope

Research in sound synthesis has shown the envelope shape

to be more definitive than an exact match of overtone

content

The attack portion is critical—a faster attack can be

confused with “brightness” (more high frequency overtones)

Considerable research has gone into the creation of “timbre

space,” a multi-dimensional plot in which timbres are

classified according to overtone content, envelope and

attack time

Measurement and Perception

Loudness

While intensity is the measurement most closely correlated to

loudness, the perception of volume is based on a number of

factors, not all of them entirely measurable.

Measurement and perception

Loudness

Perceived loudness is frequency-dependent

Perceived equal

loudness of sine

tones

This is why

many receivers

have a

Loudness knob

Equal loudness curves (Fletcher, Munson, 1930s).

Measurement and perception

Loudness

Perceived loudness is frequency-dependent

Within close frequency ranges, perceived loudness is

proportional to the cube root of intensity

Two violins playing the same pitch will generate twice the

intensity of one violin, but will not sound twice as loud

To achieve twice the volume, eight violins are required

Measurement and perception

Loudness

Perceived loudness is bandwidth-dependent

Increasing the bandwidth (component frequency

content) of a sound makes it sound louder, even if the

intensity remains constant

Despite many efforts, no one has suceeded in

creating a definitive perceptual scaling system for

loudness

Measurement and Perception

Loudness

Some have argued that estimation of loudness is not

automatic (measurable), but depends on a number of

higher-level estimations of distance, import, context, etc.

Hermann Helmholtz, On the Sensations of Tone (1885):

…we are exceedingly well trained in finding out by our

sensations the objective nature of the objects around us,

but we are completely unskilled in observing these

sensations per se; and the practice of associating them

with things outside of us actually prevents us from being

distinctly conscious of the pure sensations.

Measurement and Perception

Conclusion

Objective measurements can tell us more about sound

events

By the same token, they give us insight into what we

don’t know

This course will examine music in technical terms

This examination will give us some new insights

It will also give us an idea of where music crosses the

barrier from the objective (acoustics) to the subjective

(magic?)