The role of local government in settlement and multiculturalism

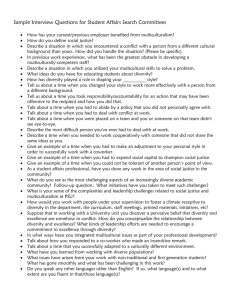

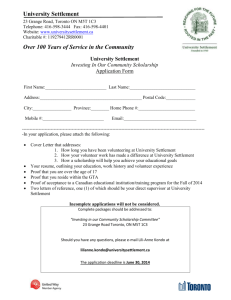

advertisement