Chapter 7

Chapter 7

On Tuesday, in Building 356, Room 111, from

5:30 to 7:30, there will be a Halloween party for students, faculty, and staff with kids. Free pizza, candy and refreshments. Come with costumes.

We’re quite behind so I’m going to try to catch up us this week – i.e. Chapters 7, 8, 9 and any parts of 10 we haven’t already covered.

Because there won’t be time for each of you to do two presentations, your 5% mark will be converted to 10%.

•

•

This chapter focuses on: transition to more service-based work

erosion of stable work increased labour market ‘flexibility’, as we saw in the Walmart video changing geography of labour

In developed countries, most people are dependent on waged or salaried labour, whereas in developing countries, some people still engage in subsistence labour – for instance, farming, though that is changing.

•

•

The latter is a doublededged sword; can you say how?

Thus, we can see that there are different kinds of labour in the world today: subsistence agriculture, often home-based crafts

(“cottage industries”), and wage/ salaried labour.

They also touch on the history of slavery and indentured servitude and note and note that there are still an estimated 12 million slaves in the world.

Source : Bing

•

•

•

The authors say that almost ½ the world’s wage labour force is in just 4 countries: China, India, the US, and Indonesia.

While labour is often buffeted by economic changes, it is not entirely passive. We saw in the video how workers were trying – against great odds – to unionize Walmart.

They cite Pahl (1988) on the hypothesized reactions of aliens as to the way labour is valued and remunerated in our society: domestic vs. workforce, boring vs. creative, shaping the wellbeing of society vs. potentially destructive.

•

They note that discrimination against women has been the norm, even – until recently

– in government legislation, but we heard in our discussion last week the issue is complex, and it is not always easy to compare what is

“work of equal value.”

Janeane in the Dean’s office was the first female

Underground miner in the Yukon!

•

•

•

As we’ve already discussed, differences in labour costs for different countries explain a lot about where certain jobs relocate (see Figure 7.1).

Even within developed countries like the U.S., there is considerable disparity in wages from one region to another, as well as differences in levels of unemployment – for instance, the Rust Belt regions, or in Spain (25% rate).

While not comparable to the upheaval of the

Industrial Revolution, the loss of stable employment in the primary and secondary industries in North America has created havoc of its own.

•

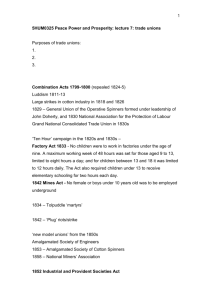

Trade union organizing – about which we heard from Emily last week – started in the 19 th century, initially with craft unions and later with unions . They achieved legitimacy only at a cost of great violence and repression.

industrial

Source : Wayne State

University

•

Some industrial unions were more radical than others, as with the Industrial Workers of the World.

• If you look at Box 7.1,

It shows that trade union density in US, Canada and the UK rose from less than

10% in the early 20 th century to a high point of

50% in the UK, around 33% in Canada, but had peaked much early (1950) in the

States. It has been declining steadily in all three ever since.

Source: Bing

•

•

A whole number of factors – some of which we’ll discuss in a moment – have been weakening trade unions: the lack of stable jobs, a growth in individualistic attitudes vs. one of ‘solidarity forever,’ a difficulty of maintaining unions in a

‘flexible’ work environment, outsourcing of formerly union jobs, and the ‘feminization’ of the labour force.

Table 7.4 shows how this has played out in 11 developed countries from 1980 to 2008. The biggest decline has been in Australia – from 49.5% to 18.6%. Sweden, progressive in so many things, has the highest rate currently – over 2/3 rds , though it has dropped 10 percentage points.

•

•

•

Governments, employers, and the media have also played divide and conquer, portraying unionized workers hypocritically as ‘privileged’ fat cats.

One way unions have attempted to counteract this is by building alliances with other social movements and making their raison d'être the broader public interest, rather than just seeking better wages and conditions for their members.

With the growth of the service sector, the scale of venues of employment has dropped from large factories – much easier to organize – to smaller, dispersed workplaces, which are much more difficult.

•

•

•

While unions have been dropping in the developed countries, they have been rising in some developing countries – for instance, South Africa (where there have been recent bloody, but successful, miners’ strikes) and

Brazil.

One thing that does not augur well for unions in the global South is the fact that the fastest growing area of employment in Africa and Latin America was in the urban informal economy (90% of all job growth in the

1990s).

On the other hand, in Argentina workers took over vacated factories and ran them themselves and in the

U.S. there has been a modest rise in workers’ cooperatives/ worker-run enterprises, and also the growth of a

U.S.

Living Wage movement in cities around the

The authors note that unions have often been associated with support for and growth of social-democratic political parties. In the

U.S., however, there has never been a viable social-democratic party; union support has mostly gone to the Democratic Party.

The labour climate – both in Canada federally and in B.C. provincially – has grown increasingly hostile, examples of which we can all probably furnish.

China – where children are employed 12 to 16 hours a day at a wage of $.14 an hour – only

Party-approved unions are permitted.

While domestic work has almost always been unpaid work, as Michael Moore’s video pointed out, in North America one wage earner used to be enough to support a whole family.

Today it rarely is and subsidized daycare is in short supply.

As noted, developed countries have seen a significant increase in service and knowledge-based jobs and the decline of primary and secondary jobs (see Table 7.1 and

Figure 7.6).

While some of these are creative, wellpaid jobs, most are repetitive boring jobs just like assembly-line positions and are badly paid (e.g., call centres), and these have been unevenly divided spatially.

Even within the same city – see the discussion in Box

7.3 about Glasgow’s dual labour market – the polarization can be stark.

With the loss of labour protection, workers in both the lower ranks and upper echelons of the service industry are increasingly subject to pressure to ‘perform’, and are faced with losing their jobs if they fail. This is a huge source of added stress.

Some have contrasted the previous regime of ‘Fordism’ with ‘post-Fordist,’ or – as the authors prefer – ‘after-

Fordist’ labour system. For a contrast of the characteristics of the two systems, see Table 7.2 on p.

160. The latter emerged in part as a response to global competition.

Many of the people filling these jobs are women.

17% of corporate officers in Canada are women; the vast majority of pink collar jobs are filled by women.

Here’s one perspective on this from an article (written by a woman no less in the Edmonton Sun ): “ Almost 30% of women opt for part-time jobs because of family responsibilities. In contrast, the vast majority of men work full-time to fulfil their traditional roles as providers.

So it should be neither a shock nor a surprise that women as a whole earn substantially less than men. They generally work less. There is no patriarchal plot to keep women poor. It is simply a matter of practicalities.

Unless you choose day care or a nanny, someone has to take care of the kids. And despite several decades of women's lib, the child-rearing responsibility still falls primarily on women.

Why? Because while most men want children, they generally balk at the mundane tasks necessary to get through a day. The poopy diapers. The baby spit-up. The food thrown all over the kitchen wall. The temper tantrums. The whiny sibling squabbles…”

While their wives were dealing with poopy diapers and baby barf, those men still involved in traditional industrial jobs – if employed by Toyota – were involved in ‘quality circles,’ job shifting, and a much more intensive hands-on management style than in the past under the Big 3 and ½. In some cases, this makes better use of their involvement.

human capital and gives them greater

In addition to core employees, many firms have opted to make use of more part-timers/ job sharers, trainees, contract workers and temps, and work that is contracted out to other firms. All of this reduces the cost of wages and benefits, and shifts some of it – as we saw in the

Walmart video – to the state.

Labour flexibility has been much more pronounced in

Anglo-American countries where deregulation has gone the farthest. As Michael Moore argues, the breakdown of Fordism represents a short of violation of the social contract, where employees demand more of their employees while offering much less in return.

Table 7.3 on p. 163 shows variations in job stability in 8 different developed countries. This seems to be twinned with higher unemployment in these countries.

Whereas people in the past could spend their whole working life with a single company (e.g., Ma Bell), nowadays people often undergo several career changes, not to speak of numerous employers or even periods of self-employment.

As people in the past derived much of their identity from their jobs, loss of that stability – especially for male workers, who derived much of their self-esteem from their work – has been psychologically devastating.

In countries like post-Soviet Russia, it has led to soaring rates of alcoholism amongst men.

In Rust Belt cities, it has led to soaring rates of crime.

Source : iir.com

Another key aspect of the geography of labour is the international migration of workers, something that is centuries old, but which has picked up in recent years, and also been affected by immigration policies. Figure

7.10 on p. 171 shows many of the regions.

source and sink

There have been trends towards letting workers in on a

‘guest worker’ basis (farmworkers and nannies) and focusing more on those with high skills and/or capital.

In addition, illegal migration remains prominent. As long as wages are significantly higher in one country than another, people will risk life and limb to get in (i.e.,

Mexico to the U.S., North Africa to Europe, etc.). Under

Bush, there were plans to build a wall across the entire border with Mexico.