Lifespan_Paper

advertisement

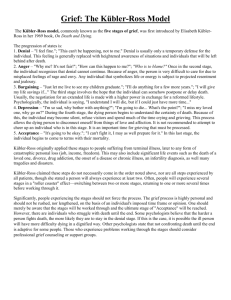

A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 1 A Look at Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s Stages of Dying and Grief Vickie Ray EPY 525 Spring 2011 A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 2 Abstract Elisabeth Kubler-Ross originally identified five stages of death and dying. She later incorporated these stages into the process we face when we grieve the loss of a loved one. She was quick to point out that the five stages are on a continuum on which we may move forward or backward at any time. The stages she identified have often been criticized. However, no one can deny the positive impact her study had on the emotional and mental care terminally ill and dying patients. A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 3 Elisabeth Kubler-Ross originally addressed the five stages of death and dying in 1969 in her book “On Death and Dying”. At this time significant gains were being made in the medical care that was available. She realized that people were living longer after being diagnosed with a terminal illness. According to Kubler-Ross (1969), this led to lower morbidity rates and an increased number of elderly people in society. The resulting change in society led to an increased number of people living with emotional and behavioral issues. Those issues included an increased fear of death and a need for coping skills to deal with the issues related to death and dying (Kubler-Ross, 1969). To better understand what the dying had to tell us and how we could help them, she began working with terminally ill patients (Nevid & Rathus, 2010,). She noted some common threads in what she saw and came up with what she perceived to be five stages in dealing with death. Kubler-Ross (1969) realized that to help these patients face death, we must help them to live fully with the time they have left. Kubler-Ross began by taking a look at the fear of death and dying. It is usually not death itself that is feared, but the dying process and the uncertainties that come with that process (Kubler-Ross, 1969). She stated that “fear is a natural emotion, but people are born with only two inherent fears: the one, of falling from high places; and the other, the fear of sudden loud noises” (1983, p. 60). Knowing this, we must accept that we acquire our fear of death from other people as we grow-up. Fear is an emotional response that a caring counselor can help their client work through. However, we must remember that sometimes there are physical needs that must be met first (Kubler-Ross, 1983). This is especially true when working with terminally ill patients. Counselors who have successfully dealt with and worked through their own death A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 4 issues can help dying patients with their fears. As with any client, it is important to help the client identify their own strengths and weaknesses. In 2005, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross and David Kessler’s book “On Grief and Grieving” took the same five stages of death and dying that Kubler-Ross identified earlier and applied them to grief. According to Kubler-Ross and Kessler (2005), we go through these stages not only after the death of a loved one, but in the case of a long, drawn-out illness, we go through these same stages in anticipation of death. This is referred to as anticipatory grief. Even though we may experience anticipatory grief, we will still experience grief and the same five stages after our loss. Even looking back to old cultures, customs, and people, we can see that death has been associated with things that are bad or frightening (Kubler-Ross, 1969). Family and friends are left to cope with feelings like anger and resentment over the death of their loved ones. This may be where Kubler-Ross saw the link between the stages of dying and grief. Since the five stages of death and dying appear to be the same for grief and grieving, I will examine the stages and how they are experienced in both situations. When faced with death and dying, there is a need for us to think about our own immortality. People react and face the possibility of their own death the same way they have handled things in their past (Kubler-Ross, 1969). If denial has been their typical coping mechanism, then that is how they will face the possibility of death. If past stressful situations have been met with open confrontation, the same can be said about how death will be faced. In either situation, some hope about the possibility of living must be present. According to Kubler-Ross (1969), the first stage, in what has become known as the five stages of dying and grief, is denial and isolation. The belief that it cannot be me was a common A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 5 theme among the patients she interviewed. Although denial may not be present at all times, it is a healthy way of dealing with a stressful situation. For most people, denial is only temporary (Kubler-Ross, 1969). Denial is also used by dying patients to help family members that are not ready to accept that their loved one is dying (Kubler-Ross, 1969). Kubler-Ross also includes isolation in the first stage. After the initial shock and denial, patients appear to be able to isolate the reality of death into a compartment that is separate from the rest of their life (Kubler-Ross 1969). This allows the patient to maintain some hope while beginning to face the reality of their own mortality. Other terms for this stage include shock, numbness, and disbelief (Friedman, 2008). Kubler-Ross and Kessler (2005) later acknowledge that over the years the term denial had been misinterpreted. They noted that for those who are dying it is more a disbelief. For those who are grieving, “denial is more symbolic than literal” (Kubler-Ross and Kessler, 2005, p. 8). It is not the denial of the death, but more a matter of coming to terms with the fact that you will never see the person again. In the context of grief, numbness, which is experienced during denial, is defined by Friedman (2008) as “the result of an overload of emotional energy in reaction to a death” (p. 39). Friedman acknowledged that numbness is experienced by many people, but he maintained that it is not a stage. He also notes that a counselor can cause harm by insisting that the client is in denial when they are not. As a counselor, the important thing, whether you believe denial is a stage or not, is to listen and understand what your client is telling you. Kubler-Ross identified the second stage as anger. Individuals that have moved to this stage have recognized that they are going to be able to get through their situation (Kubler-Ross, 2005). Anger can range from mild to strong and be aimed at a variety of targets from the A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 6 situation to a myriad of people (Kubler-Ross, 1969). At times the anger appears almost random. During grief, anger may even be directed at the loved one we have lost or even God (KublerRoss & Kessler, 2005). Friedman (2008) acknowledges that there are often things that happen, relative to the death of a loved one, that cause us to feel anger. However, it is not a universal feeling and therefore is not a stage (Friedman, 2008). Anger often surfaces ahead of other feelings and emotions that are harder to accept and manage (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Anger can be very difficult for friends and family to accept, especially when it is directed at God. They do not know what to say or do and are uncomfortable being around someone experiencing anger. However, “anger is a necessary stage of the healing process” (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005, p. 12). An empathetic counselor can recognize a person’s need to experience and express their anger during death or the grieving process. This allows the person to feel unconditional positive regard. Only by allowing our self to feel all the anger we are experiencing can we get to the feelings underneath. Anger gives us the strength we need to get by until we are able to accept the pain of the loss that is tucked away under the anger (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). The next stage is bargaining. This stage can take on several forms. Before death, bargaining is a time to make realistic and unrealistic promises, usually to God, if He will heal or grant more time (Kubler-Ross, 1969). According to Kubler-Ross (1969), these promises may be the result of some perceived guilt. For the person grieving the loss of a loved one, it becomes a series of “what if...” statements. Bargaining also moves from the past to the future after the loss of a loved one (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). For example, we may ask God to spare our family from any other tragedies. A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 7 Just as with the first two stages, the bargaining stage is an important step in the healing process. It can provide a brief respite from the pain of loss (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). During the bargaining process our mind works through all the other possible scenarios we have created and settles into the conclusion that our loved one is truly gone (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). While examining this stage, Friedman (2008) recognizes that it is natural for someone who is dying to try and bargain. However, it does not make sense for someone who is grieving the loss of a loved one. When the label yearning is used for this stage instead of bargaining, it is a more realistic description for someone who is grieving (Friedman, 2008). Once bargaining has allowed us to accept the reality of our circumstances, we must now face the situation head-on. This moves us into the fourth stage which is depression. Although depression can be a mental illness, it is a natural response to the realization that there has been a great loss (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). This could be the loss of a loved one or, for the dying patient, the loss of a healthy, productive life. “Depression is a way for nature to keep us protected by shutting down the nervous system so that we can adapt to something we feel we cannot handle” (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005, p. 21). For the dying patient there are two types of depression, reactive and preparatory (KublerRoss, 1969). Reactive depression is the result of worrying about issues surrounding those that will be left behind. This could include worry over finances, the care of household responsibilities, or the care of children. Preparatory depression occurs when the dying patient begins to realize all the love losses that will occur (Kubler-Ross, 1969). Caregivers, family and friends may be able to help the patient through their reactive depression by assisting the patient with things like childcare and reorganization of household A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 8 responsibilities (Kubler-Ross, 1969). It is much more difficult to help with preparatory depression. This is something the patient must work through alone (Kubler-Ross, 1969). Sometimes the only thing we can do is sit quietly with the patient or pray with them. Only by letting the patient completely and fully work through preparatory depression, can acceptance be achieved (Kubler-Ross, 1969). Depression is a time to allow the sadness and full extent of the loss to wash through your mind (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Not doing so is like trying to hold back floodwaters with a dam that has leaks. The floodwater is still there but continuously seeps through. By opening the dam fully, the floodwaters can wash through to the other side and rebuilding and healing can begin. Well meaning friends and family may want to try and lift the spirits of the person experiencing depression. This is usually because they are uncomfortable being around all that sadness (Kubler-Ross and Kessler, 2005). As long as depression is the normal reaction to the loss being experienced and does not turn into clinical depression, it is beneficial and necessary to the healing process. Friedman (2008) identifies the following symptoms that are common to both people who are grieving and those who are clinically depressed: lack of concentration, disruptions in sleeping patterns, changes in eating patterns, roller-coaster of emotions, decline in energy level. He believes this is a normal reaction to loss and should not be defined as a stage. A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 9 Working through the previous four stages allows us to move on to the fifth stage which Kubler-Ross (1969) identifies as acceptance. Acceptance does not equal happiness (KublerRoss, 1969). For patients who can look back and see the purpose, meaning, and fulfillment that their life has brought, acceptance appears to come without much assistance (Kubler-Ross, 2005). Others may struggle and require more help to achieve the peace that comes with acceptance. Acceptance does not occur all at once, but is a process that occurs as we slowly integrate the new reality into our life (Kubler-Ross, 2005). It is the realization that we have begun to live again without the all consuming feelings and emotions associated with loss, whether the loss is one of health or a loved one. Friedman (2008) argues that “the concept of acceptance is confusing, if not moot” (p.71) since there is no denial in the beginning. Through every stage, Kubler-Ross (1969) found hope to be the common constant. Webster (1991) defines hope as a “desire accompanied by expectation of or belief in fulfillment” (p. 186). It is hope that provides the mind with the strength and spirit to endure (Kubler-Ross, 1969). Once hope is gone, death seems to be imminent. Developmentally, children do not have the same understanding of death as adults (Kubler-Ross, 1969). As they age and move through different developmental stages, they may experience the grief again with the new understanding they gain (Himebauch et al., 2008). Children under the age of three may express grief in the form of separation anxiety (Himebauch et al., 2008; Kubler-Ross, 1969). From age two to six, children may perceive death as temporary (Himebauch et al., 2008). They may also believe that the death is the result of something they did or said. Usually around age nine, children realize that death is permanent (Kubler-Ross, 1969). However, they may not believe that it can happen to them (Himebauch et al., 2008). Adolescents have an adult understanding of death but may have difficulty identifying and A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 10 expressing feelings (Himebauch et al., 2008; Kubler-Ross, 1969). Children need to be listened to as they struggle to deal with death and grief. They need a significant adult to talk with and a safe environment to express their emotions (Himebauch et al., 2008). Kubler-Ross and Kessler (2005) acknowledge that movement through the five stages is fluid and non-linear. Every person may not even experience every stage. There is also no set length of time that each individual stage will last. At any time we may experience any of the stages. Even the achievement of acceptance does not mean that we will no longer feel anger or depression over our loss. However, the more fully we allow our self to feel each emotion, the more we are able to heal (Kubler-Ross, 1969). Every person’s loss is unique. No two people will react or feel the same way (KublerRoss & Kesler, 2005). Each person must travel their own personal journey. When we arrive on the other side, our life will be different. Therefore, the way we live our life will also be changed. By having some idea of what to expect, hopefully we will be better equipped to make the journey, wherever it may carry us. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross used the information she discovered in her study of death and dying to give voice to those who seemed to have no voice. What she learned helped friends, family, and caregivers understand the needs of the dying. The information she learned help spur the initiation of the hospice movement. Although there have been many opponents to her five stages of death and dying, the information she shared improved the care and treatment for the terminally ill and dying. A Look at the Stages of Dying and Grief 11 References Friedman, R., & James, J. W. (2008). The myth of the stages of dying, death and grief. Skeptic, 14(2), 37-41. Himebauch, A., Arnold, R. M., & May, C. (2008). Grief in children and developmental concepts of death #138. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11(2), 242-243. Kubler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. New York, NY: Macmillan. Kubler-Ross, E. (1983). On children and death. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. Kubler-Ross, E., & Kessler, D. (2005). On grief and grieving. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. (1991). New Webster’s dictionary and Roget’s thesaurus. New York, NY: Ottenheimer Publishing. Nevid, J.S., & Rathus, S. A. (2010). Adolescent and adult development: going through changes. In C. Johnson (Ed.), Psychology and the challenges of life (pp. 454-491). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc