weiten6_PPT09

advertisement

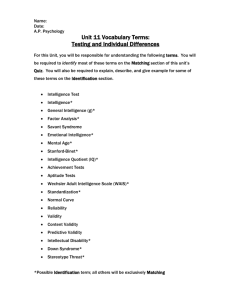

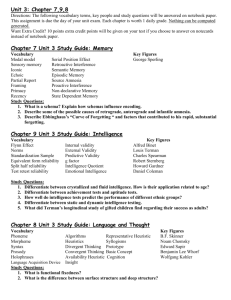

Chapter 9 Intelligence and Psychological Testing Principle Types of Psychological Tests Mental ability tests –Intelligence – general –Aptitude – specific Personality scales –Measure motives, interests, values, and attitudes Table of Contents Fig 9.4 – Criterion-related validity. To evaluate the criterion-related validity of a pilot aptitude test, a psychologist would correlate subjects’ test scores with a criterion measure of their aptitude, such as ratings of their performance in a pilot training program. The validity of the test is supported if a substantial correlation is found between the two measures. If little or no relationship exists between the two sets of scores, the data do not provide support for the validity of the test. Table of Contents Fig 9.3 – Correlation and reliability. As explained in Chapter 2, a positive correlation means that two variables covary in the same direction; a negative correlation means that two variables covary in the opposite direction. The closer the correlation coefficient gets to either –1.00 or +1.00, the stronger the relationship. At a minimum, reliability estimates for psychological tests must be moderately high positive correlations. Most reliability coefficients fall between 70 and .95. Table of Contents Fig 9.5 – Construct validity. Psychologists evaluate a scale’s construct validity by studying how scores on the scale correlate with a variety of variables. For example, some of the evidence on the construct validity of the Expression Scale from the Psychological Screening Inventory is summarized here. This scale is supposed to measure the personality trait of extraversion. As you can see on the left side of this network of correlations, the scale correlates negatively with measures of social introversion, social discomfort, and neuroticism, just as one would expect if the scale is really tapping extraversion. On the right, you can see that the scale is correlated positively with measures of sociability and self-acceptance and another index of extraversion as one would anticipate. At the bottom, you can see that the scale does not correlate with several traits that should be unrelated to extraversion. Thus, the network of correlations depicted here supports the Table of Contents idea that the Expression Scale measures extraversion. The Evolution of Intelligence Testing Sir Francis Galton –Hereditary Genius (1869) Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon –Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale –Mental age (1905) Lewis Terman (1916) –Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale –Intelligence Quotient (IQ) – MA/CA x 100 David Wechsler (1955) –Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Table of Contents Table of Contents Fig 9.6 – Subtests on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS). The WAIS is subdivided into a series of tests that yield separate verbal and performance (nonverbal) IQ Table of Contents scores. Examples of low-level (easy) test items that closely resemble those on the WAIS are shown on the right. Fig 9.7 – The normal distribution. Many characteristics are distributed in a pattern represented by this bell-shaped curve. The horizontal axis shows how far above or below the mean a score is (measured in plus or minus standard deviations). The vertical axis is used to graph the number of cases obtaining each score. In a normal distribution, the cases are distributed in a fixed pattern. For instance, 68.26% of the cases fall between +1 and –1 standard deviation. Modern IQ scores indicate where a person’s measured intelligence falls in the normal distribution. On most IQ tests, the mean is set at an IQ of 100 and the standard deviation at 15. Thus, an IQ of 130 means that a person scored 2 standard deviations above the mean. Any deviation IQ score can be converted into a percentile score, which indicates the percentage of cases obtaining a lower score. The mental classifications at the bottom of the figure are descriptive labels that roughly correspond to ranges of IQ scores. Table of Contents Reliability and Validity of IQ tests reliable – correlations into the .90s Qualified validity – valid indicators of academic/verbal intelligence, not intelligence in a truly general sense Exceptionally –Correlations: –.40s-.50s with school success –.60s-.80s with number of years in school Predictive of occupational attainment, debate about predictiveness of performance Table of Contents Extremes of Intelligence: Mental Retardation Diagnosis based on IQ and –IQ 2 or more SD below mean –Adaptive skill deficits –Origination before age 18 4 adaptive testing levels: mild, moderate, severe, profound –Mild most common by far Causes: –Environmental vs. Biological Table of Contents Table of Contents Fig 9.9 – The prevalence and severity of mental retardation. The overall prevalence of mental retardation is roughly 1 to 3% of the general population. The vast majority (85%) of the retarded population is mildly retarded. Only about 15% of the retarded population falls into the subcategories of moderate, severe, or profound retardation. Table of Contents Fig 9.10 – Social class and mental retardation. This graph charts the prevalence of mild retardation (IQ 60 to 69) and more severe forms of retardation (IQ below 50) in relation to social class. Severe forms of retardation are distributed pretty evenly across the social classes, a finding that is consistent with the notion that they are the product of biological aberrations that are equally likely to strike anyone. In contrast, the prevalence of mild retardation is greatly elevated in the lower social classes, a finding that meshes with the notion that mild retardation is largely a product of unfavorable environmental factors. (Source: Adapted from Popper and Steingard, 1994) Table of Contents Extremes of Intelligence: Giftedness Identification issues – ideals vs. –IQ 2 SD above mean standard –Creativity, leadership, special talent? practice Stereotypes – weak, socially inept, emotionally troubled –Lewis Terman (1925) – largely contradicted stereotypes –Ellen Winner (1997) – moderately vs. profoundly gifted Giftedness and high achievement – beyond –Renzulli (2002) – intersection of three factors –Simonton (2001) – drudge theory and inborn talent IQ Table of Contents Intelligence: Heredity or Environment? Heredity –Family and twin studies –Heritability estimates Environment –Adoption studies –Cumulative deprivation hypothesis –The Flynn effect Interaction –The concept of the reaction range Table of Contents Fig 9.12 – Studies of IQ similarity. The graph shows the mean correlations of IQ scores for people of various types of relationships, as obtained in studies of IQ similarity. Higher correlations indicate greater similarity. The results show that greater genetic similarity is associated with greater similarity in IQ, suggesting that intelligence is partly inherited (compare, for example, the correlations for identical and fraternal twins). However, the results also show that living together is associated with greater IQ similarity, suggesting that intelligence is partly governed by environment (compare, for example, the scores of siblings reared together and reared apart). (Data from McGue et al., 1993) Table of Contents Fig 9.13 – The concept of heritability. A heritability ratio is an estimate of the portion of variation in a trait determined by heredity—with the remainder presumably determined by environment—as these pie charts illustrate. Typical heritability estimates for intelligence range between a high of 70% and a low of 50%, although some estimates have fallen outside this range. Bear in mind that heritability ratios are estimates and have certain limitations that are discussed in the text. Table of Contents Fig 9.15 – Reaction range. The concept of reaction range posits that heredity sets limits on one’s intellectual potential (represented by the horizontal bars), while the quality of one’s environment influences where one scores within this range (represented by the dots on the bars). People raised in enriched environments should score near the top of their reaction range, whereas people raised in poor-quality environments should score near the bottom of their range. Genetic limits on IQ can be inferred only indirectly, so theorists aren’t sure whether reaction ranges are narrow (like Ted’s) or wide (like Chris’s). The concept of reaction range can explain how two people with similar genetic potential can be quite different in intelligence (compare Tom and Jack) and how two people reared in environments of similar quality can score quite differently (compare Alice and Jack). Table of Contents Cultural Differences in IQ Heritability as an Explanation –Aurthur Jensen (1969) –Herrnstein and Murray (1994) – The Bell Curve Environment as an Explanation –Kamin’s cornfield analogy – socioeconomic disadvantage –Steele (1997) - stereotype vulnerability Table of Contents Fig 9.16 – Genetics and between-group differences on a trait. Kamin’s analogy (see text) shows how between-group differences on a trait (the height of corn plants) could be due to environment, even if the trait is largely inherited. The same reasoning presumably applies to ethnic group differences in the trait of human intelligence. Table of Contents New Directions in the Study of Intelligence Increased emphasis on specific abilities –Moving beyond Spearman’s g –Guilford’s 150 distinct mental abilities. –Fluid vs. crystallized intelligence Biological Indexes of Intelligence –Reaction time and inspection time Cognitive Conceptualizations of Intelligence –Sternberg’s triarchic theory and successful intelligence Expanding the Concept of Intelligence –Gardner’s multiple intelligences –Goleman’s emotional intelligence Table of Contents Fig 9.18 – Spearman’s g. In his analysis of the structure of intellect, Charles Spearman found that specific mental talents (S1, S2, S3, and so on) were highly intercorrelated. Thus, he concluded that all cognitive abilities share a common core, which he labeled g for general mental ability. Table of Contents Fig 9.19 – Guilford’s model of mental abilities. In contrast to Spearman (see Figure 9.19), J. P. Guilford concluded that intelligence is made up of many separate abilities. According to his analysis, people may have as many as 150 distinct mental abilities that can be characterized in terms of the operations, contents, and products of intellectual activity. Table of Contents Fig 9.22 – Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence. Sternberg’s model of intelligence consists of three parts: the contextual subtheory, the experiential subtheory, and the componential subtheory. Much of Sternberg’s research has been devoted to the componential subtheory, as he has attempted to identify the cognitive processes that contribute to intelligence. He believes that these processes fall into three groups: metacomponents, performance components, and knowledgeacquisition components. Table of Contents