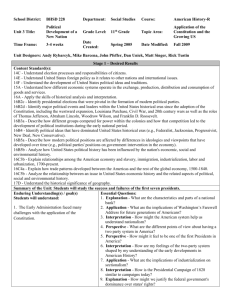

1797- XYZ Affair President Adams sent three envoys to France to

advertisement

1797- XYZ Affair President Adams sent three envoys to France to negotiate a new agreement. French Minister Talleyrand demanded a personal bribe of $250,000 and loan of $12 million dollars to France. When word of the affair became public, the American people were incensed. They demanded war with France. Adams refrained from declaring war, but a quasi-war took place for two years. Relations between the United States and France had gone steadily downhill from the time of the Genet mission. Tensions were further exacerbated by the Jay Treaty, signed between the United States and Great Britain. In addition, French ships had begun preying on American merchant ships. When Pinckney was sent to France to replace James Monroe, the French refused to receive him. In an attempt to avoid war, Adams agreed to send a special delegation to attempt to negotiate a treaty with France. The delegation included John Marshall, Elbridge Gerry and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. The representatives arrived in France, and were told that they would not be received by the French Foreign Minister Talleyrand unless certain political condition were met. Furthermore, they were told that, as a precondition to any talks, a bribe would have to be paid to members of the Directorate, and a loan given to France. Finally, they were told that they were in danger of arrest. Needless to say they decided to return home. When Adams received word of what had happened, he informed the Senate that the mission was not successful. He did not want to release complete information on the meetings, fearing that it would result in a war cry against France. The Republicans did not believe that the mission had been unsuccessful, and demanded that Adams release the full transcripts of the dispatches from France. They expected to show that France was receptive to an agreement. Finally, Adams, who was being attacked mercilessly, compiled and released the complete transcripts. Soon, war fervor was sweeping the nation. Adams did not wish to go war with France, but American ships were being attacked almost as soon as they left New York Harbor. Adams decided to build a navy and give it the task of protecting American ships and attacking French privateers. The Navy was officially established in 1798. Four large frigates, which had been originally authorized by Congress in 1794, were rushed to completion. They were the "Constellation," the "United States," the "Chesapeake" and the "President." They represented the very best in ship design, combining speed and firepower. In addition, cities throughout the eastern seaboard built ships for the government, at their own expense. By 1800, the US Navy was fielding a fleet of 49 warships of various sizes. Furthermore, over 100 merchant vessels were armed and authorized not only to defend themselves but to take aggressive actions when possible. The US Navy was given the task of protecting US ships and attacking French privateers and naval vessels. In the two years of warfare between France and the US, American ships sank or captured nearly 90 French vessels on the high seas. In the most successful sea battle of the war, the USS "Constellation" captured the French naval frigate "Insurgent," reportedly one of France's best vessels. By 1800, the French realized the error of their ways, and agreed to accept an American delegation without precondition. An agreement was swiftly reached, and the hostilities came to an end. For those not at sea, the fighting between France and the US may have seemed like a "quasi-war;" but for those serving in the US Navy or on merchant ships, it was a war in every way that mattered. 1. What does “Quasi War” mean? 2. Did Adams want to go to war? Did he not? With which political party did he side? 3. Why do we call this event the “XYZ” affair? 4. What was the eventual outcome of the event? Veto of the Bank of the United States (1832) Andrew Jackson Introduction Andrew Jackson took his battle with "the Monster," the Second Bank of the United States, very personally. From the moment he became president, Jackson launched a war against the bank, determined to kill the beast that he saw destroying the republic. When Congress renewed the bank's charter in July 1832, Jackson, with help from Amos Kendall and Roger Taney, composed the following veto message. Congress was not able to override Jackson's veto and the Bank of the United States ceased to exist. Source: To the Senate: ...A bank of the United States is in many respects convenient for the Government and useful to the people. Entertaining this opinion, and deeply impressed with the belief that some of the powers and privileges possessed by the existing bank are unauthorized by the Constitution subversive of the rights of the States, and dangerous to the liberties of the people, I felt it my duty at an early period of my Administration to call the attention of Congress to the practicability of organizing an institution combining all its advantages and obviating these objections. I sincerely regret that in the act before me I can perceive none of those modifications of the bank charter which are necessary, in my opinion, to make it compatible with justice, with sound policy, or with the Constitution of our country. The Bank of the United States enjoys an exclusive privilege of banking under the authority of the General Government, a monopoly of its favor and support, and, as a necessary consequence, almost a monopoly of the foreign and domestic exchange. The powers, privileges, and favors bestowed upon it in the original charter, by increasing the value of the stock far above its par value, operated as a gratuity of many millions to the stock-holders. Every monopoly and all exclusive privileges are granted at the expense of the public, which ought to receive a fair equivalent. The many millions which this act proposes to bestow on the stockholders of the existing bank must come directly or indirectly out of the earnings of the American people. It is due to them, therefore, if their Government sell monopolies and exclusive privileges, that they should at least exact for them as much as they are worth in open market. The value of the monopoly in this case may be correctly ascertained. The twenty-eight millions of stock would probably be at an advance of 50 per cent, and command in market at least $42,000,000, subject to the payment of the present bonus. The present value of the monopoly, therefore, is $17,000,000, and this the act proposes to sell for three millions, payable in fifteen annual installments of $200,000 each. But this act does not permit competition in the purchase of this monopoly. It seems to be predicated on the erroneous idea that the present stockholders have a prescriptive right not only to the favor but to the bounty of Government. It appears that more than a fourth part of the stock is held by foreigners and the residue is held by a few hundred of our own citizens, chiefly of the richest class. For their benefit does this act exclude the whole American people from competition in the purchase of this monopoly and dispose of it for many millions less than it is worth. This seems the less excusable because some of our citizens not now stockholders petitioned that the door of competition might be opened, and offered to take a charter on terms much more favorable to the Government and country. But this proposition, although made by men whose aggregate wealth is believed to be equal to all the private stock in the existing bank, has been set aside, and the bounty of our Government is proposed to be again bestowed on the few who have been fortunate enough to secure the stock and at this moment wield the power of the existing institution. I can not perceive the justice or policy of this course. If our Government must sell monopolies, it would seem to be its duty to take nothing less than their full value, and if gratuities must be made once in fifteen or twenty years let them not be bestowed on the subjects of a foreign government nor upon a designated and favored class of men in our own country. It is but justice and good policy, as far as the nature of the case will admit, to confine our favors to our own fellow citizens, and let each in his turn enjoy an opportunity to profit by our bounty. In the bearings of the act before me upon these points I find ample reasons why it should not become a law. It has been urged as an argument in favor of rechartering the present bank that the calling in its loans will produce great embarrassment and distress. The time allowed to close its concerns is ample, and if it has been well managed its pressure will be light, and heavy only in case its management has been bad. If, therefore, it shall produce distress, the fault will be its own, and it would furnish a reason against renewing a power which has been so obviously abused. Is there no danger to our liberty and independence in a bank that in its nature has so little to bind it to our country? The president of the bank has told us that most of the State banks exist by its forbearance. Should its influence become concentrated, as it may under the operation of such an act as this, in the hands of a selfelected directory whose interests are identified with those of the foreign stockholders, will there not be cause to tremble for the purity of our elections in peace and for the independence of our country in war? Their power would be great whenever they might choose to exert it; but if this monopoly were regularly renewed every fifteen or twenty years on terms proposed by themselves, they might seldom in peace put forth their strength to influence elections or control the affairs of the nation. But if any private citizen or public functionary should interpose to curtail its powers or prevent a renewal of its privileges, it can not be doubted that he would be made to feel its influence. Should the stock of the bank principally pass into the hands of the subjects of a foreign country, and we should unfortunately become involved in a war with that country, what would be our condition?All its operations within would be in aid of the hostile fleets and armies without. Controlling our currency, receiving our public moneys, and holding thousands of our citizens in dependence, it would be more formidable and dangerous than the naval and military power of the enemy. If we must have a bank with private stockholders, every consideration of sound policy and every impulse of American feeling admonishes that it should be purely American. Its stockholders should be composed exclusively of our own citizens, who at least ought to be friendly to our Government and willing to support it in times of difficulty and danger. It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes. Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions. In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society the farmers, mechanics, and laborers who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government. Nor is our Government to be maintained or our Union preserved by invasions of the rights and powers of the several States. In thus attempting to make our General Government strong we make it weak. Its true strength consists in leaving individuals and States as much as possible to themselves in making itself felt, not in its power, but in its beneficence; not in its control, but in its protection; not in binding the States more closely to the center, but leaving each to move unobstructed in its proper orbit. Questions to Consider 1. What is a bank? What does it do? 2. List 3 reasons Jackson is against the Second Bank of the United States. 3. From what you know of Andrew Jackson's political philosophy, what do you think is the main reason he dislikes this bank? 4. How does Jackson include the relationship of the national government to the state governments and the power of the people in his veto message? 5. Do you think the government needed a national bank in 1832? Why or why not? 6. If you believe the federal government needed to have a bank, how would you organize it? Justify your answer. Kentucky Resolution Thomas Jefferson, November 16, 1798, Kentucky Resolution [Rough Draft] Excerpt I [S]pecial provision has been made by one of the amendments to the Constitution which expressly declares, that "Congress shall make no law respecting an Establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press," thereby guarding in the same sentence, and under the same words, the freedom of religion, of speech, and of the press... Excerpt II That, therefore the act of the Congress of the United States passed on the 14th day of July 1798, entitled "An act in addition to the act for the punishment of certain crimes against the United States," which does abridge the freedom of the press, is not law, but is altogether void and of no effect. 1. Do you think that the Kentucky Resolution was for or against the Sedition Act? Why? 2. What document did the author, Thomas Jefferson, refer to in his response to the Sedition Act? 3. Why did Jefferson use this example from the Constitution to respond to the Sedition Act? 4. What did Mr. Jefferson think of the Sedition Act? 5. What evidence did Mr. Jefferson use to support his opinion? The Alien and Sedition Acts (1798) An Act Concerning Aliens (excerpt) SECTION 1. Be it enacted by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That it shall be lawful for the President of the United States at any time during the continuance of this act, to order all such aliens as he shall judge dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States, or shall have reasonable grounds to suspect are concerned in any treasonable or secret machinations against the government thereof, to depart out of the territory of the United States, within such time as shall be expressed in such order, which order shall be served on such alien by delivering him a copy thereof, or leaving the same at his usual abode, and returned to the office of the Secretary of State, by the marshal or other person to whom the same shall be directed. And in case any alien, so ordered to depart, shall be found at large within the United States after the time limited in such order for his departure, and not having obtained a license from the President to reside therein, or having obtained such license shall not have conformed thereto, every such alien shall, on conviction thereof, be imprisoned for a term not exceeding three years, and shall never after be admitted to become a citizen of the United States. SECTION 3. And be it further enacted, That every master or commander of any ship or vessel which shall come into any port of the United States after the first day of July next, shall immediately on his arrival make report in writing to the collector or other chief officer of the customs of such port, of all aliens, if any, on board his vessel, specifying their names, age, the place of nativity, the country from which they shall have come, the nation to which they belong and owe allegiance, their occupation and a description of their persons, as far as he shall be informed thereof, and on failure, every such master and Commander shall forfeit and pay three hundred dollars, for the payment whereof on default of such master or commander, such vessel shall also be holden, and may by such collector or other officer of the customs be detained. And it shall be the duty of such collector or other officer of the customs, forthwith to transmit to the office of the department of state true copies of all such returns. 1. What authority does this act give the President? 2. What groups of people are being targeted by this act? An Act in Addition to the Act, Entitled “An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes Against the United States (excerpt) SECTION 2. And be it farther enacted, That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to stir up sedition within the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States, or any act of the President of the United States, done in pursuance of any such law, or of the powers in him vested by the constitution of the United States, or to resist, oppose, or defeat any such law or act, or to aid, encourage or abet any hostile designs of any foreign nation against United States, their people or government, then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years. 3. What does this act prohibit? 4. Which groups of people are being targeted by this act? Alexander Hamilton's Financial Program Annotation: The most pressing problems facing the new government were economic. As a result of the Revolution, the federal government had acquired a huge debt: $54 million including interest. The states owed another $25 million. Foreign credit was unavailable. Ten days after Alexander Hamilton (1754-1804) became Secretary of the Treasury, Congress asked him to report on ways to solve the nation's financial problems. Hamilton immediately realized that he had an opportunity to create a financial program that would embody his political principles. Born in the West Indies, Hamilton never developed the intense loyalty to a state that was common among Americans of the time. He intended to use government fiscal policies to strengthen federal power at the expense of the states and "make it in the immediate interest of the moneyed men to co-operate with government in its support." Such an alliance, in his view, was indispensable for the survival and growth of the United States. In his "Report on Public Credit," Hamilton proposed that the government assume the entire indebtedness of both the federal government and the states, and retire the old depreciated obligations by borrowing new money at a lower interest rate. This proposal ignited a firestorm of controversy since the states of Maryland, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Virginia had already paid off their war debts and saw no reason why they should be taxed to pay off other states' debts. Others opposed the scheme because it would provide profits to speculators who had bought bonds from revolutionary war veterans for as little as 10 or 15 cents on the dollar. For six months, bitter debate raged in Congress, before Hamilton approached Thomas Jefferson with a compromise proposal. In exchange for southern votes on his debt plan, Hamilton promised his support for locating the future national capital on the banks of the Potomac River, the border between two southern states, Maryland and Virginia. In the following letter Roger Sherman (1721-1793), a member of Congress from Connecticut and the author of "the Connecticut Compromise" at the Constitutional Convention, explains why he supports Hamilton's policy on the debt and outlines the ideal relationship between federal and state governments. Document: The report of the Secretary [Hamilton] has been under consideration for some time respecting a provision for the national debt. There has been a long debate respecting a discrimination between the Securities in the hands of the original creditors and those which have been transferred [i.e., bought up by speculators]--but it was finally decided by a large majority against a discrimination, the motives were that the Securities were by government made transferrable, & payable to the bearer, and therefore the transfer vested the whole property in the purchaser, if there were no fraud or compulsion.... No common market price could be fixed without great inequality & injustice in many instances, and a particular inquiry into the circumstances of every case would be impracticable; besides the public faith had been pledged after the transfers in most of the cases of speculation by issuing new securities to the purchasers in their own names. It was therefore concluded that government could do nothing to impair or alter the contracts consistent with good faith. The assumption of the debts of the several states incurred for the common defense during the late war, is now under consideration. The Secretary of the Treasury has been directed to report what funds can be provided for them in case they should be assumed. His report is contained in one of the enclosed papers. He supposed that sufficient provision may be made for the whole debt, without resorting to direct taxation, if so I think it must be an advantage to all the states, as well as to the creditors. Some have suggested that it will tend to increase the power of the federal government & lessen the importance of the state governments, but I don't see how it can operate in that manner, the constitutions are so framed that the government of the United States & those of the particular states are friendly, & not hostile, to each other, their jurisdictions being distinct, & respecting different objects, & both standing upon the broad basis of the people, will act for their benefit in their respective spheres without any interference. And the more strength each have to attain the ends of their Institutions the better for both, and for the people at large. I have ever been of opinion that the governments of particular States ought to be supported in their full vigour, as the security of the civil & domestic rights of the people more immediately depend on them, that their local interests & customs can be best regulated and supported by their own laws; and the principal advantages of the federal government is to protect the several States in their enjoyment of those rights, against foreign invasion, and to preserve peace, and a beneficial intercourse between each other, and to protect & regulate their commerce with foreign nations. 1. Summarize the basic concept behind Hamilton’s plan. 2. Why did Jefferson agree to get his southerners to pass the bill. 3. What does the author of this document believe? Where does he side on the issue?