Spring 2012

advertisement

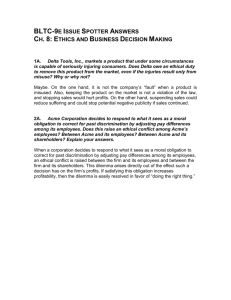

1 Securities Regulation Professor Bradford Spring 2012 Exam Answer Outline The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. In some cases, the result is unclear; the position taken by the answer is not necessarily the only justifiable conclusion. I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on your printed exam. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class: Question Question Question Question Question Question 1: 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: Range Range Range Range Range Range 2-8; 3-8; 2-9; 3-8; 0-7; 0-7; Average Average Average Average Average Average = = = = = = 4.78 5.33 4.94 4.83 3.33 4.83 Total (of unadjusted exam scores, not final grades): Range 2.42-7.05; Average = 4.65 All of these grades are on the usual law school scale, with 9 being an A+ and 0 being an F. If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. 2 Question One Flack’s Liability Flack has no primary liability under Rule 10b-5 or the Exchange Act. One does not make a false statement for purposes of 10b -5 merely by drafting it. Janus Capital. The person who makes a false statement is the person with the authority to release it and control over its contents. Id. Here, that would be Zappa. The press release was approved and released by Prez, Zappa ’s President, and was not even attributed to Flack. Flack could be liable for aiding and abetting, if Zappa violated Rule 10b -5, but only in an action brought by the SEC. There is no private cause of action against someone who aids or abets a Rule 10b -5 violation. Central Bank. In an SEC action, Flack would be under section 20(e) of the Exchange Act if (1) Zappa violated the Act; (2) Flack acted knowingly or recklessly; and (3) Flack substantially assisted the violation. The latter two requirements are clearly met. Flack knew the press release was false. Flack’s drafting of the press release substantially assisted the violation , if there was one. Thus, Flack’s liability as an aider and abettor turns on Zappa ’s primary liability, discussed below. Zappa’s Liability Zappa made a false statement—the press release was clearly false and, under Janus Capital, Zappa clearly made this statement. It was released in Zappa’s name and authorized by Prez, who had authority to act on Zappa’s behalf. The press release must have been made “in connection with the purchase or sale of any security,” but that requirement appears to be met. The question is whether the fraud touches on a securities transaction or is reasonably calculated to influence the investing public. Here, Prez knew that the r elease would affect investors and, in fact, that was the whole point —to influence the market price. Reliance does not appear to be a major issue. Zappa is traded on NASDAQ and is a reporting company. The market for its stock is probably an efficient one. If the information in the release was material, it was undoubtedl y reflected in the market price, and the fraud-on-the-market theory would apply. Basic. Zappa would be liable only if it acted with scienter—an intent to deceive. Hochfelder. Most lower courts have held that recklessness is scienter. Veep knew that Zappa did not have a new contract, but Veep was not involved in any way with making the statement. It is usually not enough to establish 3 corporate scienter that someone in the organization knew the truth. The person who actually makes or authorizes the statement for the company must have knowledge of the fraud or act recklessly. Prez does not appear to have had actual knowledge of the fraud. But he may have acted recklessly. He relied solely on Flack, an outsider, for information about his own company. A simple phone call by either Prez or his secretary would have revealed the fraud. Prez appears to have been willfully blind; he just didn’t care if it was true or not. His lack of care arguably is extreme enough to constitute recklessness rather than mere negligence. If so, scienter has been shown. The false statement must also be material. A misstatement is material if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important. TSC Industries. The fake contract only involves a one percent increase in sales, and release of the information appears to have a negligible effect on Zappa’s stock price. But what may make such a minor claim material is its ability to push the stock price over $45, which in turn would prevent an undoubtedly material stock option from being triggered. Given the importance of the $45 threshold, information that might not otherwise be material could be. But that leads to another question. To recover for a violation of 10b -5, a plaintiff must show loss causation—that the fraud caused the loss. What really caused the stock price to fall was not the revelatio n that contract was false, but the trigger of the stock purchase and the resulting dilution. Absent the fraudulent press release, the purchase option would have been triggered anyway, with the same negative effect on the stock price. Thus, the fraud does not seem to have caused the loss. But for the fraud, the same loss would have occurred. If Flack had committed a violation, Zappa might be liable as a controlling person under section 20(a) of the Exchange Act. Prez arguably induced the violation by telling Flack to think of ways to get the stock price up, and Prez’s recklessness could constitute a lack of good faith. Although Hearst was an independent contractor, Zappa arguably had control over it with respect to the press release. But a controlling person is liable only if the person controlled violated the Act, and, as discussed earlier, Flack is not liable. 4 Question Two Instruction I.D of Form S-3 establishes the requirements for an automatic shelf registration. Acme’s offering is eligible to be an automatic shelf registration only if: (1) The offering is eligible for shelf registration under Rule 415. (2) Acme meets the requirements to use Form S-3. (3) Acme is a well-known seasoned issuer (WKSI). Rule 415 Requirements To be eligible for a shelf registration, the offering must fall within one of the categories in Rule 415(a). Since an automatic shelf registration must be registered on Form S-3 anyway, the most obvious possibility is subsection (a)(1)(x). If Acme’s offering is eligible for registration on Form S -3, subsection (x) clearly applies. The shares are to be sold on “an immediate, continuous, or delayed basis” and the sales will be by the registrant, Acme. Rule 415 has other requirements, but those won’t be a problem. Subsection (a)(2) doesn’t apply to securities in paragraph (a)(1)(x). Under (a)(3), Acme must furnish the undertakings required by Item 512(a) of Regulation S-K—essentially undertakings to update the information in the registration statement. This is an at-the-market offering of equity securities, as defined in Rule 415(a)(4). Acme is selling its common stock into an existing trading market, the New York Stock Exchange, at the market price. But all that subsection (a)(4) requires is that the offering come within (a)(1)(x), and that’s the subsection Acme will be using. Finally, subsection (a)(5) says the registration statement will only be effective for three years, but that’s the period during which Acme intends to sell. Eligibility to Use Form S-3 Acme must be eligible to use Form S-3. To be eligible, Acme must meet the registrant requirements of Instruction I.A of Form S-3 and the offering must meet the offering requirements of Instruction I.B. Registrant Requirements Acme is organized under U.S. law (Del.) and its principal place of business is in the United States (N.D.), meeting the requirements of A .1. It is an Exchange Act reporting company, as required by A .2. We would need to 5 know if it has been reporting for at least 12 months and has filed all of its reports in a timely fashion, as required by A.3. We also need to know whether Acme has, since the filing of its last year-end financial statements, materially defaulted on any preferred stock dividends, debt, or long term leases. If so, it would be ineligible under A .5. Transaction Requirements Acme’s offering must also fall within one of the transact ion requirements in Instruction I.B. This transaction probably fits within B.1. It is an offering for cash and the aggregate market value of Acme’s voting and non-voting common equity is $630 million, well above the $75 million level. As long as at least $75 million of that is held by non-affiliates, Acme is eligible to use Form S-3. None of the other possibilities fits. Paragraph B.6 wouldn’t work because the amount to be sold, $300 million, is more than 1/3 of the aggregate market value of common equity without even excluding any shares held by affiliates. Whether Acme is a WKSI For a shelf registration to be automatically effective, the issuer must be (1) a well-known seasoned issuer under Rule 405(1)(i)(A) or (2) a WKSI under 405(a)(i)(B), if the offering meets the transaction requirements of Instruction I.B.1. Acme’s offering will be within I.B.1, so the offering would be eligible for shelf registration if Acme falls within either category of WKSI. Acme could be a WKSI within the meaning of Rule 405(a)(1)(i)(A), assuming it meets the registrant requirements of instruction I .A of Form S3, discussed earlier. The market value of its common equity, including non voting common equity, is $725 million, more than the $700 million cutoff. However, if Acme’s affiliates own more than $25 million of its outstanding equity, Acme would not be a WKSI because the $700 figure excludes securities owned by affiliates. If Acme does not fall within 405(a)(1)(i)(A), Acme would not be a WKSI. Subsection (a)(1)(i)(B) clearly does not apply to Acme. The question indicates that Acme has no outstanding securities other than its common stock, so Acme has not issued any securities other than common equity. Certain companies are disqualified from being WKSIs, but the problem indicates that Acme is not an ineligible issuer, (iii), an asset -backed issuer (iv), or an investment company or business development company, (v). 6 Therefore, assuming it has been a reporting company for more than a year, is timely in its reports, and the common equity held by its affiliates is less than $25 million, Acme is eligible to do an automatic shelf registration. 7 Question Three The relevance of these factors depends on whether the particular investment involves stock, a note, or some other type of investment. Corporate Stock—All Factors Irrelevant If the investor is buying ordinary corporate stock, none of the factors makes any difference. Ordinary common stock is a security, regardless of any of these facts. Landreth Timber. Factor No. 1 If the investor is receiving a note for his investment, the first factor could be relevant under the third factor of the Reves family resemblance test, which looks at the reasonable expectations of the investing public. The language in the brochure could be used to show that the investors did not reasonably believe this to be an investment. However, not every part of the family resemblance test needs to be met for a note to be a security, and this is probably the least important factor, so it could still be a security. If the investment is some other kind of instrument, the Howey investment contract test would apply. Under that test, what the brochure says appears irrelevant. An investment contract must involve an investment of money with an expectation of profits, but the language in the brochure doesn’t matter, only the actual characteristics of the investment. Factor No. 2 If the investor is receiving a note, this could be relevant under the second part of the family resemblance test—the plan of distribution. Obviously, with one investor, there could be no common trading for speculation or investment, and the note is not offered to a broad segment of the public. But, again, the Reves test does not depend on any single factor, so it could still be a security. If the Howey investment contract test applies, this would be relevant under the common enterprise requirement. There would be no horizontal common enterprise if there’s only one investor, assuming there aren’t additional investors resulting from other, prior offerings. However, if the promoter offered to multiple investors and only one accepted, the promoter could still be offering a security. If the horizontal common enterprise test is not met, the investment could be an investment contract, and thus a s ecurity, only in jurisdictions which hold that a vertical common enterprise—a common enterprise between the investor and the promoter—satisfies Howey. 8 Factor No. 3 This factor doesn’t matter under either Reves or Howey. The Edwards case makes it clear that a fixed rate of return is sufficient expectation of profits for purposes of the Howey test. And a note by definition often involves a fixed rate of return. A fixed rate of return would still be a profit motivation for purposes of the first prong of the family resemblance test under Reves. If there is a fixed rate of return, Landreth is less likely to apply, even if the investment is “stock.” One of the ordinary characteristics of stock is dividends contingent on an apportionment of profits. 9 Question Four Section 5 of the Securities Act Section 5(b)(1) of the Securities Act makes it unlawful to transmit a “prospectus” for a security with respect to which a registration statement has been filed, unless that prospectus meets the requirements of section 10. Seller’s registration statement has been filed, so § 5(b)(1) applies. And the June 1 report could be a prospectus. A prospectus is, among other things, a written offer to sell. Sec. 2(a)(10). The report is written. Rule 405 defines “written communication” to include “graphic communication” and it defines “graphic communication” to include electronic web sites. An offer to sell is any attempt to dispose of or solicitation of an offer to buy a security, § 2(a)(3), and the SEC has indicated that anything that conditions the market to buy the security can be an offer to sell. Broker’s distribution of information about Issuer and its offering could generate interest in buying the Issuer stock. And Broker, as a participant in the offering, clearly has a motivation to generate such interest. The Rule 139 Safe Harbor The SEC has promulgated a couple of safe harbors that allow brokers to distribute reports without running afoul of section 5. Rule 137, one of those safe harbors, does not help Broker because it only applies to non participants in the offering. Rule 137(a). Rule 138 only applies when the report relates to common stock and the offering is of non-convertible preferred stock or debt, or vice versa, and that isn’t the case here. Thus, Broker’s only option is Rule 139. Rule 139 authorizes two types of reports: (1) issuer -specific research reports and (2) industry reports. Rule 139(a)(1), dealing with issuer-specific reports is not available. The issuer must meet the registrant requirements of Form S-3, 139(a)(1)(i)(A)(1), and Issuer is not eligible to use Form S-3. For Broker to use Rule 139(a)(2), Issuer must be a reporting company, Rule 139(a)(2)(i) and it may not be a blank check company, a shell company, or an issuer of penny stock. Rule 139(a)(2)(ii). It is unclear whether Issuer meets these requirements; if not, the Rule 139(a)(2) safe harbor is unavailable to Broker. Broker must distribute the report in the regular course of its business, (a)(2)(v), but that appears to be the case. The distribution is irregular and sporadic, but it is done as part of Broker’s regular course of business. 10 Broker must also include in the reports similar information about a substantial number of issuers in the industry or sub-industry. Rule 139(a)(2)(iii). This requirement is probably not met. Each of the two reports only includes information about three companies out of twelve. That doesn’t seem to be a “substantial number” of issuers. Broker must also be including similar information about the issuer and its securities in similar reports. Rule 139(a)(2)(v). Issuer also appeared in the January report, but information about the offering was not included, because it had not begun at the time. Broker does include information about offerings when they occur, but is that enough to meet (a)(2)(v)? Finally, the information about Issuer in the report must be given no more space or prominence than information about the other companies, Gamma and Delta. Rule 139(a)(2)(iv). We don’t know if that requirement is met. In short, Rule 139 looks problematic, and therefore, Broker may violate section 5(b)(1) if it distributes the June report. Other Possible Safe Harbors Rule 433, the free-writing prospectus rule, would not help. Issuer is not eligible to use Form S-3, so it would not be a seasoned issuer. See Rule 433(b)(1). Therefore, to use Rule 433, the report would have to be accompanied by Issuer’s preliminary prospectus and include a cautionary legend. See Rule 433(b)(2)(i), (c)(2). There is no indication that Broker did that. Rule 134 would not be available because the information included in Broker’s report (for example, financial statements) is beyond what Rule 134(a) allows. Other possible safe harbors, such as Rule 169, are available only to the issuer, and would not help Broker. See Rule 169(a) (“by or on behalf of the issuer”). 11 Question Five Section 5 and the registration requirements of the Securities Act apply to resales as well as offerings by an issuer. The usual statutory exemption for resales is section 4(1), bolstered by two safe harbors, Rule 144 and 144A. Rule 144A clearly is not available here. It applies only to resales to qualified institutional buyers, and the buyer, Daughter, is clearly not an institution. See Rule 144A(a)(i). RULE 144 Is Seller an Affiliate? The requirements of Rule 144 depend on whether Seller is an affiliate of Beta, as defined in 144(a)(1)—in particular, whether he controls Beta. Control is defined as the power “to direct or cause the direction of the management and policies of a person” and can include control through contract. Rule 405. Here, Beta cannot engage in any extraordinary transactions without Seller’s approval—either actions outside the ordinary course of business or involving more than $100,000 in assets. But Seller does not have any power over smaller transactions, is not involved in day -today management, and has no authority over the policies of Beta. He also does not have the power to force Beta to file a registration statement. It is unclear if he has enough control to make him an affiliate. If Seller is Not an Affiliate If Seller is not an affiliate, Rule 144(b)(1)(ii) applies because Beta has not been subject to the reporting requirements of the Exchange Act for 90 days prior to the sale. The Rule 144(b)(1)(ii) safe harbor is available to Seller only if he is selling “restricted securities” and only if he meets the condition in paragraph (d). The common stock is clearly a restricted security. Where securities are acquired in an exchange, they acquire the characteristic of th e securities that were exchanged. The original preferred shares were acquired in a private offering, so the common would be restricted securities within the meaning of subsection (a)(3)(i). Seller must also comply with paragraph (d). Since Beta has not been a reporting company for 90 days, (d)(1)(ii) applies. A minimum of one year must have elapsed since Seller acquired the securities from the issuer. However, if the securities were acquired from the issuer in exchange for other securities, the holding period runs from the date the original securities were acquired. Rule 144(a)(3)(ii). Thus, the holding period runs from June 12 1, 2010, when he acquired the preferred stock, which he exchanged to get the common. He sold on April 30, 2012, obviously more than a year later, so he has met the required holding period. If he is not an affiliate, the sale is exempt and he did not violate the Securities Act. If Seller Is an Affiliate If Seller is an affiliate, Rule 144(b)(2) applies. He must meet all of the conditions of 144. Since Beta has not been a reporting company for 90 days, the public information requirement of 144(c)(2) applies. Beta probably meets this requirement because of the information filed and publicly available in its initial Exchange Act report. As previously indicated, Seller meets the holding period requirement of (d). He is also within the limit on the amount of sales in subsection (e). The limit is the greater of the weekly reported trading volume (essentially, zero here) or 1% of the amount outstanding. That limit would be 1% of 500,000, or 5,000 shares, and S eller is within that limit. But subsection (f) requires that the securities be sold in brokers’ transactions. The problem says nothing about a broker, so this condition is probably not met If Seller is an Affiliate—Outside the Safe Harbor Even if he doesn’t qualify for the Rule 144 safe harbor, Seller might still have an argument under section 4(1) itself. Section 4(1) covers transactions not involving an issuer, underwriter or dealer. Ne ither Seller nor his daughter is an issuer or a dealer. The question is whether there is an underwriter involved. Seller is not selling for the issuer, so he would be an underwriter only if he purchased from the issuer with a view to distribution. Investment Intent. Again, the common stock acquires the characteristics of the preferred stock for which it was exchanged. The question is whether Seller intended to resell or to hold the stock. The bend point in the case law for establishing investment intent is typically two years, and Seller held the stock, from the original issue of the preferred, for only 18 months. However, the two-year presumption was established when Rule 144 itself had a two -year holding period. Now that the Rule 144 period is shorter, perhaps a court could be convinced that the holding period under 2(a)(11) ought to be correspondingly shorter. Distribution. Even if he can’t establish investment intent, Seller is an underwriter only if his resale is a distribution. Distribution has two different meanings, but they’re equivalent here. Before securities have come to rest, resales inconsistent with the issuer’s exemption, in this 13 case section 4(2), constitute a distribution. For resales by affiliates, even after the securities have come to rest, “distribution” is usually equated with “public offering” under section 4(2), and that depends on whether the buyer can fend for herself. Daughter is unsophisticated and unaccredited and has no relationship to Beta, so she doesn’t have the sophistication and access to information that would be required under section 4(2). However, there is not an exact equation between public offering under section 4(2) and distribution under section 2(a)(11), and Seller’s sale is limited to one person, so this still might not be a distribution. If this part of the definition of underwriter doesn’t apply, the second part clearly doesn’t apply. No one here is selling for the issuer or for a control person. Even if Seller is a control person, no one is selling on his beha lf. Selling for oneself does not make one an underwriter. 14 Question Six Rule 147 Rule 147 would not be available. Lone Star is a resident of Texas under subsection (c)(1)(i), but it does not meet all of the doing business requirements. All of its gross revenues are derived from operations in Texas. Rule 147(c)(2)(i). And at least 80% of its assets are located in Texas. Rule 147(c)(2)(ii). It has total assets worth $50 million and it has only spent $3 million on the Oklahoma plant. Its principal office is in Texas. Rule 147 (c)(2)(iv).The problem is Rule 147(c)(2)(iii). Lone Star does not intend to use at least 80% of the net proceeds “in connection with the operation of a business or of real property, the purchaser of real property located in, or the rendering of services within” Texas. It will use the money to continue construction of the plant in Oklahoma, and to support the eventual operation of that business in Oklahoma. The prior offering was probably not confined to Oklahoma, but integration is not a problem. The Rule 147(b) six-month safe harbor would protect this offering from integration and the Rule 502(a) safe harbor would protect the Rule 505 offering from integration. Carfix appears to be an acceptable purchaser under Rule 147(d)(1) because its principal office is in Texas. However, the professors would not be, since they teach across the country and would not all have their principal residences in Texas. Rule 147(d)(2). The general partnership would be acceptable. It’s formed for the purpose of the offering, but that’s not a problem, because all of its beneficial owners are Texas residents. Rule 147(d)(3). Regulation A Regulation A would also not be available. It is also limited to non -reporting companies. Rule 251(a)(2). Otherwise, it would be available. The of fering amount limit is $5 million, less than the $3 million Lone Star intends to sell. And only offerings pursuant to Regulation A in the last 12 months reduce that limit, so the Rule 505 sales would not affect th e limit. Integration would also not be a problem. Rule 251(c) says Regulation A offerings will not be integrated with any prior offers or sales. Rule 504 Rule 504 is not available. Issuers that are subject to the reporting requirements of the Exchange Act may not use it. Rule 504(a)(1). In addition, Lone Star is seeking to raise $3 million and the 504 limit is $1 15 million. Further, that amount must be reduced by amounts sold pursuant to a 3(b) exemption in the last 12 months, and the Rule 505 offering is a § 3(b) exemption, so the effective amount is now $0. The previous R. 505 offering will not present an integration problem because of the Rule 502(a) safe harbor. General solicitation is generally prohibited in Regulation D offerings, including some, but not all, Rule 504 offerings, but gene ral solicitation is not a problem because Broker has a preexisting relationship with all of the offerees. Rule 505 Rule 505 is also not available. First, the offering amount is limited to $5 million, reduced by the amount of, among other things, § 3(b) offerings in the last 12 months. Rule 505(b)(2)(i). Subtracting the $4 million sold seven months ago in the 505 offering, that only leaves $1 million, less than the $3 million Lone Star needs to raise. Rule 505 also limits the number of purchasers to 35, Rule 505(b)(2)(ii), and this offering would exceed that limit. The 20 college professors would count as 20 purchasers. Carfix would ordinarily count as one purchaser, since it was not formed solely for purposes of investing in this offering. Rule 501(e)(1)(3). However, it is an accredited investor under Rule 501(a)(3), so it is excluded from the count. Rule 501(3)(1)(iv). Magna was formed solely for this offering, so it would not be counted as one purchaser. Rule 501(e)(2). We have to count each partner as a separate purchaser. The twenty partners with net worths in excess of $1 million are accredited investors. Rule 501(a)(5). As accredited investors, they aren’t counted. Rule 501(e)(1)(iv). However, the other 20 don’t appear to be accredited, so they would count. That results in a total of 40 purchasers, in excess of the limit. Rule 506 Rule 506 also has a 35-purchaser limit. Rule 506(b)(2)(i). The rules for counting are exactly the same, so this would also be violated. The Rule 506(b)(2)(ii) requirement would not be a problem. The 20 college professors do not appear to be accredited, but their finance and investment background probably gives them “such knowledge and experience in financial and business matters that . . . [they] . . . are capable of evaluating the merits and risks of the prospective investment. Carfix, with assets in excess of $20 million, would be an accredited investor under Rule 501(a)(3). However, Magna would not be an accredited investor. I t doesn’t fall within Rule 501(a)(3) because it was formed for the specific purpose of acquiring the securities offered. It doesn’t fall within Rule 501(a)(8) because not all of its 16 partners are accredited investors. Therefore, Magna would have to meet the sophistication requirement. That shouldn’t be a problem, however, because all of its investors are sophisticated, so whoever is making the investment decisions on its behalf would undoubtedly meet the sophistication requirement. Rules 144 and 144A Neither of these exemptions applies because they deal with resales, and this is an original offering by the issuer, not a resale.