Intro Part 2 PowerPoint

advertisement

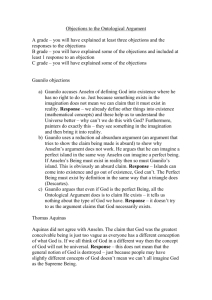

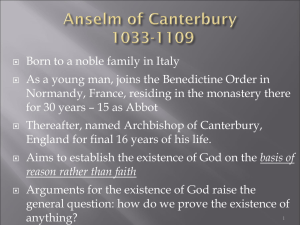

Introduction to Philosophy PART TWO: Philosophy & Religion The Problem of Faith & Reason Early Christian Thought Greeks Jewish Tradition Cause of the problem Two sources: faith & reason Classic Questions Points of Disagreement Points of Agreement Biblical tradition: anti-philosophy Biblical tradition: pro-philosophy The Problem of Faith & Reason 11th & 12th Century Introduction Reason as predominant Faith as predominant Monastic reforms Peter Damian St. Bernard Anselm’s View John Scotus Erigena Roscelin Abelard Reason & Faith Proof through deduction Synthesis of faith & reason-Aquinas Theology & philosophy The Nature & Existence of God Questions Metaphysical questions What is the nature of God? Does God exist? Epistemic Questions How do we know the nature of God? How do we know God exists? Reason & Logic View A priori reasoning and God A Priori Reasoning St. Anselm, Descartes, Leibniz A posteriori reasoning and God A posteriori reasoning St. Aquinas, David Hume The Nature & Existence of God Rejection of Reason & Logic View Approaches God can be known through faith. God can be known through mystical experience/divine revelation. God cannot be known by any means. Pascal’s Wager Regresses & Absurdity Regress & Absurdity Methodology Introduction Circular Regress Defined Form & Examples A requires A A requires B, B requires C…Z requires A Job-Experience Infinite Regress Defined Form 1 requires 2 2 requires 3 3 requires 4 X requires X+1 Regresses & Absurdity The Evil Bureaucrat Reductio Ad Absurdum (Reducing to Absurdity) Defined Form #1 Assume P is true. Prove that assuming P leads to something false, absurd or contradictory. Conclude that P is false. Form #2 Assume P is false. Prove that assuming P is false leads to something false, absurd or contradictory. Conclude that P is true. Example Regresses & Absurdity Example Using a regress in a Reductio Ad Absurdum Introduction Example St. Anselm Background Background (1033-1109) Goal St. Anselm’s Ontological Argument Anselm’s A Priori Argument for God’s Existence The fool understands “God”: a being than which nothing can be conceived (NGCBC). Fool says there is no God. The understands what he hears. What he understands is in his understanding. It is one thing for an object to be in the understanding. It is another to understand the object exists. Painter analogy The fool is convinced something exists in his understanding. From Understanding to Reality Whatever is understood is in the understanding. That than which NGCBC cannot exist in the understanding alone. If NGCBC exists in the understanding alone, it is something GCBC. St. Anselm’s Ontological Argument Suppose it exists only in the understanding-it can be conceived to exist in reality, which is greater. If NGCBC exists in the understanding alone it is GCBC. This is impossible. There exists NGCBC in reality & understanding. God cannot be conceived not to exist NGCBC exists so truly it cannot be conceived not to exist. It is possible to conceive of a being that which cannot be conceived not to exist and this is greater than one that can be conceived not to exist. If NGCBC can be conceived not to exist, it is not NGCBC. This is a contradiction. There is so truly a NGCBC that it cannot even be conceived not to exist. St. Anselm’s Ontological Argument God alone cannot be conceived not to exist God exists and cannot be conceived not to exist. If one could conceive of a being better than God, the creature would rise above its creator, which is absurd. Everything, except God, can be conceived not to exist. God alone exists more truly than all others and hence in a higher degree. Whatever else exists does not exist so truly so it exists to a lesser degree. So the fool denies God because he is a fool. Gaunilo’s Answer to the Argument of Anselm Challenge & Doubt Gaunilo’s Challenge Suppose it is said a being which cannot be even conceived in terms of any fact, is in the understanding. Gaunilo accepts that this being is in his understanding. He will not accept that it has a real existence until a proof is given. Gaunilo’s Doubt Anselm claims this being exists-otherwise the being which is greater than all will not be greater than all. Gaunilo doubts that this being is greater than any real object. The only existence it has is the same as when the mind, from a word heard, tries to form the image of an unknown object. Gaunilo’s Answer to the Argument of Anselm How is the existence of that being proved from the assumption that it is greater than all other beings? He does not admit that this being is in his understanding even in the way which many objects whose real existence is uncertain and doubtful, are in his understanding. It should be proved first that this being really exists. Then, from the fact that it is greater than all, we would conclude it also subsists in itself. Gaunilo’s Answer to the Argument of Anselm Gaunilo’s Perfect Island Argument The Perfect Island There is an island that is impossible to find, the “lost” island. This island has inestimable wealth and no owner or inhabitant. Hence it is more excellent than all other countries, which are inhabited. If someone claims there is such an island, Gaunilo would understand his words. The parity of reasoning: But suppose he said: You cannot doubt that this most excellent of island exists somewhere. You have no doubt that it is in your understanding. It is more excellent not to be in the understanding alone, but to exist in the understanding and in reality. Hence, the island must exist. If it does not exist, any land which really exists will be more excellent. Hence, the island understood to be more excellent will not be more excellent. Gaunilo’s Answer to the Argument of Anselm Gaunilo’s Criticism of this line of reasoning. If someone tried to persuade him by such reasoning, he would assume the person was jesting or regard him or himself a fool. It ought to be shown that: The hypothetical excellence of this island exists as a real and indubitable fact. It is not an unreal object, or one whose existence is uncertain in Gaunilo’s understanding. A note of Gaunilo’s method. He is combining parity of reasoning with a reduction to absurdity. Parity of reasoning: to use reasoning that parallels the reasoning in question. In this case Gaunilo is using the same line of reasoning as Anselm. Reducing to absurdity: to prove that a claim is implausible by drawing an absurd or contradictory conclusion from it. In this case Gaunilo draws an absurd conclusion by using Anselm’s method. He thus concludes that the method is flawed. Anselm’s Reply to Gaunilo The Island Anselm’s Summary of Gaunilo’s Objection One should suppose an island in the ocean, which surpasses all lands in its fertility. Because of the impossibility of discovering what does not exist is called a lost island. There can be no doubt that this island truly exists in reality. Hence one who hears it described understands what he hears. Anselm’s Challenge If any shall devise anything existing in reality or in concept alone (except that than which a greater cannot be conceived) to which he can apply Anselm’s reasoning, he will discover it. Anselm’s Reply to Gaunilo Anselm’s Reply Part one: God cannot be conceived not to be. This being than which a greater is inconceivable cannot be conceived not to be. Because it exists on so assured a ground of truth. Otherwise it would not exist at all. Part Two: The dilemma So, if one claims he conceives this being not to exist, at the time when he conceives of this either he conceives of a being than which a greater is inconceivable or he does not conceive at all. If he does not conceive, he does not conceive of the nonexistence of that of which he does not conceive. If he conceives, he certainly conceives of a being which cannot be even conceived not to exist. If it could be conceived not to exist, it could be conceived to have a beginning and an end. This impossible. Anselm’s Reply to Gaunilo Part Three: It’s inconceivable. He who conceives of this being conceives of a being which cannot be even conceived not to exist. But he who conceives of this being does not conceive that it does not exist. If he does so, then he conceives what is inconceivable. The nonexistence of that than which a greater cannot be conceived is inconceivable. St. Thomas Aquinas Background (1224-1274) Early Life Son of the count of Aquino Imprisoned in a tower Albert the Great Eastern Orthodox Church Mystic Experience Canonized in 1323 1879 Pope Leo XIII The Ox Nickname The flying Cow Works 25 Volumes Summa Theologica St. Thomas Aquinas Aristotle & Aquinas Complete Works 12th-13th Century: the complete works of Aristotle became available in Europe. Aristotle’s works presented a systematic and developed philosophy. Conflict Aristotle: the world is eternal and uncreated. Apparently did not accept personal immortality. Ibn Rushd’s commentaries on Aristotle Neo-Platonism Aquinas’ View Aristotle’s view could be adopted without heresy. Regarded Aristotle as a rich intellectual behavior. “The Philosopher.” Aristotle as a pagan lacking divine revelation. St. Thomas Aquinas Shift from Plato to Aristotle Platonic notions of the eternal & other worldliness. Aristotle’s works presented a systematic and developed philosophy. Faith & Reason Reconciliation: Augustine Sin damaged reason Grace Faith as necessary condition for philosophical understanding Reconciliation: Aquinas Sin did not criple our rational facilities Reason as autonomous source of knowledge Distinguishes between philosophy & theology Two sources of knowledge Theology yields knowledge via faith & revelation Philosophy yield knowledge via reason and experience St. Thomas Aquinas Truth: Christian teachings that a matter of faith Known via revelation Beyond reason, not contrary to reason Objections and problems Cannot be proven/disproven by reason Examples: trinity, incarnation, original sin, etc. Truth: Empirical Knowledge & Self Evident Philosophical Principles Not known via revelation Examples: Aristotle’s logic, biological functions of heart Truth: Overlap of philosophy & theology Known via revelation or reason Examples: God’s existence & qualities, existence of the soul, immortality, natural moral law Two Type of Theology Revealed supernatural Natural theology Conflict St. Thomas Aquinas Aquinas’ Epistemology & Metaphysics Epistemology Aristotle’s Influence Blank slate No innate knowledge Senses provide reason with content Intellect Intellect Passive & active Passive operations Objects of experience Active aspect Potential Natural process St. Thomas Aquinas Metaphysics: Hierarchy Actuality & Potentiality Prime matter-potentiality Forms-actuality God-pure actuality Change Great Chain of Being Hierarchy Variety Angels Knowable Purpose Objective Values St. Thomas Aquinas Metaphysics: Existence & Essence Essence & Existence Essence Existence God His essence entails He exists God Necessity Rejection of ontological argument Empirical experience St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways Introduction Introduction Aristotle General Form If the world has X, then God exists. The world has X. God exists. Cosmological argument Assumption: infinite regress of causes is not possible St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways The First Way (the Way of Motion) Some things are in motion Whatever is moved is moved by another Potentiality A thing moves Reduction from potentiality to actuality Fire Actuality & potentiality in different respects Hot Cold Impossible to be both moved and mover. Whatever is moved is moved by another Moved by another St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways Moved by another This cannot go on to infinity No first mover No other mover Moved by first mover Staff First mover This everyone understands to be God St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways The Second Way ( Efficient Cause) Order of efficient causes Nothing can be the efficient cause of itself Not possible to go on to infinity Efficient causes following an order First Intermediate Take away the cause If no first cause, then neither intermediate nor ultimate If it is possible to go on to infinity No first efficient cause No ultimate effect No immediate efficient causes Plainly false First efficient cause to which everyone gives the name God. St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways The Third Way (Possibility & Necessity) Possible to be and not to be Impossible for these to always exist One time there was nothing Nothing would exist now Impossible for anything to have begun to exist Thus now nothing would be in existence There must exist something whose existence is necessary Every necessary thing either has its necessity cause by another or not Impossible to go on to infinity Therefore we must admit the existence of a being As per efficient causes Having of itself its own necessity Not receiving it from another Causing necessity in others This all men speak of as God St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways The Fourth Way (Gradation) Among beings are some more and some less More or less are predicated by resemblance to a maximum There is something truest, best, noblest There is something most in being The maximum in any genus is the cause of all in that genus Fire There must be something which is the cause of being, goodness, perfection This being we call God St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways The Fifth Way (Governance of the World) Things that act from knowledge act for an end Evident from acting in the same way Whatever lacks knowledge must be directed Therefore some intelligent being directs all natural things This being we call God St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways Common Mistakes in Interpreting the 5 Ways Everything must have a cause Does not assume this What is potential must be cause by what is actual Created beings The world has a beginning in time Does not attempt to prove this Does not disprove Aristotle’s eternal world and unmoved mover Possibility of an eternal universe First cause Eternal flame God as a continuously sustaining cause Not possible to prove an eternal world St. Bonaventure Beginning in time Revelation, not proof St. Thomas Aquinas: Five Ways Common Criticisms Five beings Five different beings Being distinguished by qualities Perfect and unlimited being Two perfect beings would be identical Cannot be two unlimited beings “And this everyone understands to be God” Different from the personal God Not a complete view of God Important qualities Way of gradation Gottfried Leibniz Background German Culture Stagnant Languages Reformation & 30 Years Way (1618-1648) No other significant thinkers Background for Leibniz Early Years Professional career Diplomacy Works Logical Method Leibniz: Arguments for God God Proofs for God’s Existence Ontological argument Eternal & necessary truths Design argument Cosmological argument Proof of God’s Existence for God’s Existence God Supreme substance Unique, universal, necessary Nothing else independent Incapable of limits, as much reality as possible. Perfection God is absolutely perfect Perfections from God, imperfections from their own nature Leibniz: Arguments for God Existence God is the source Existence of a necessary being God alone must exist if he is possible Leibniz: Arguments for God The Cosmological Argument Two principles on which reasons are founded Contradiction False True Sufficient reason Reason why it is so Known Two kinds of truth Those of reasoning Necessary Analysis Those of fact Contingent Possible Leibniz: Arguments for God Sufficient Reason Contingent truths Resolution Contingents Sufficient/final reason God Necessary substance Change exists eminently God suffices Leibniz: Problem of Evil Best of All Possible Worlds The best world God’s Choice “best of all possible worlds” Single event Entirety God’s choice Infinity of possible universes Reason Best Wisdom Goodness Power Diversity Only God is perfect God must pick the best Variety & order Leibniz: Problem of Evil No Better World Possible Intellectualist view The problem and reply God lacks goodness Defects Big picture Not made for us alone The Best God’s will Impossible Reply Denial of Pantheism Infinite divisibility Infinity is not a whole God Universe is not an animal or substance Leibniz: Problem of Evil Evil as Privation Whence does evil come? Origin of Evil-Ancients Origin of Evil-intellectualist view Matter Uncreated Eternal verities Original imperfection Errors Understanding & Necessity Plato God & Nature Understanding Necessity Understanding Primitive Form Ideal Cause Formal cause Evil is deficient Leibniz: Problem of Evil The Analogy of the Boat Boats The Analogy Cargo Slower Receptivity Slower Current is like God Inertia is like imperfection Slowness is like defects Current causes motion not retardation God causes perfection Limitation in receptivity God causes the material element of evil not the formal Current is the material cause of retardation but not the formal It causes the speed but not the limit God and sin Defects God produces all that is positive, good and perfect Imperfections arise from the original limitations God cannot give all Degrees of perfection David Hume Background (1711-1776) Life & Philosophical Writings Born 1711 Edinburgh University France Works A Treatise of Human Nature An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals Natural History of Religion Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion History of England Died 1776 (still dead today) Hume’s Philosophy of Religion: Existence of God Skepticism Introduction Skeptical A priori & a posteriori arguments fail Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion Cleanthes: a posteriori arguments Demea: faith & a priori arguments Philo: skeptic All arguments for God fail First cause arguments Reason Matters of fact Existence A priori reasoning Conceiving Demonstrable Relations of ideas Hume’s Philosophy of Religion: Existence of God Causation Assumption Causality as habit House analogy Universe No constant conjunction No empirical argument based on causation Rejection of Design Mechanistic assumption Resembles animal/vegetable more than a machine Matching environment Ideally suited Hume’s Philosophy of Religion: Existence of God Five Problems Introduction First Problem Finite effect Cause as great as the effect Second Problem Like effects Perfect Perfect universe Falls short No other universes Third Problem As good as possible Many worlds Labor lost Slow improvement Hume’s Philosophy of Religion: Existence of God Fourth Problem One God Analogy Fifth God as physical being Hume’s Problem of Evil Establishing the Misery Philo-Feeling Demea-Truth Learned Poets Demea-Writers & Misery Truth Miseries Cannot be doubted Philo-Agreement Misery Eloquence Feel it more All complain Philo-Leibniz Denied Hume’s Problem of Evil Demea-Leibniz Demea-Catalog of Evils Earth War Necessity Birth Weakness Philo-Chain of Misery First Denial Prey Torment Enemies Demea-Man as an exception Partial exception Master lions, tigers and bears Hume’s Problem of Evil Philo-Man creates his own demons Demea-Society Real enemies Imaginary enemies Death Timid flock Man is the greatest enemy of man Torments Dread Demea-Problems External problems Labor & poverty Few Goods of life Stranger visiting the world Pleasure Hume’s Problem of Evil Philo-Misery Cleanthes No reason to complain Why stay alive Objection: false delicacy Reply: delicacy Objection: rest Rely: rest leads to disappointment Sees problems in others, not self Demea-Reply to Cleanthes Cleanthes is unique Hume’s Problem of Evil Philo-The Problem of Evil Philo challenges Cleanthes Power argument Power is infinite Wills No happiness Does not will Wisdom Argument Anthropomorphism Wisdom is infinite Never mistaken Not to felicity Not for that purpose Conclusion Benevolence Epicurus’ Questions Willing but not able Able, but not willing Able and willing Hume’s Problem of Evil More Problem of Evil Philo-Refutation of Divine Benevolence Cleanthes If proven unhappy, all religion ends. Demea-big picture reply to the problem of evil Cleanthes: nature has a purpose & intention Preservation and propagation No resources for the happiness of individuals Racking pains Mirth Divine benevolence Mystics Point & moment Other regions & future Benevolence Cleanthes-Enjoyments outweigh pains Deny misery & wickedness Exaggeration Health Pleasure Happiness Hume’s Problem of Evil Philo-Pain exceeds pleasure More violent & durable Pain Torment Pleasure Pain Death Philo-No foundation for religion unless Human life is happy Existence is desirable Philo-Not what we expect Estimate Uncertain Does nothing Not what we expect Hume’s Problem of Evil Philo-why any evil at all? Not by chance Contrary to his intention Attack Philo-Compatibility Compatible Mere possibility Pure from impure Insufficient Insufficient Philo-Conclusion Faith alone Hume & the Immorality of the Soul Soul & Substance Reason Difficult to prove Metaphysical, moral or physical Metaphysics Unknown Substance Immaterial & material Confused & Imperfect Unknown Cause & effect Abstract reasoning Spiritual Substances analogous to Material Substance Analogy Clay Dissolved Immortal substance Hume & the Immorality of the Soul Memory, Consciousness & Substances Animals Loss of memory & consciousness Incorruptible & ingenerable Existence before birth Animals Souls Moral Arguments God’s Justice Present Life Moral arguments Punishment Attributes This universe Present Life Fostering fears Fear the Future Fear Riches Present life Deceit Hume & the Immorality of the Soul Humans & Animals Women First cause Ordained by Him Nothing Punishment without purpose Proportion in punishment Mortal soul Religious theory Equal No Object of God’s Punishment Powers Parity of reasoning Proportional Damnation Additional concerns Heaven & Hell Lenience Infancy Hume & the Immorality of the Soul Physical Physical Arguments Sleep Argument Proportion Argument Analogy Dissolution Souls of Animals Proportional Dissolution Condition Argument Connected Sleep Mortal Analogy Change Argument Flux Immortal Hume & the Immorality of the Soul Infinite Number of Souls Infinite Planets Lack of Argument Argument Insensibility Argument Horrors & Passions Horrors Nothing in vain Postpone Death Passions Hopes Defending a Negative Advantage Arguments New logic Divine revelation Immanuel Kant Background Personal Information 1724-1797 Contributions Arguments for God Introduction Reason cannot be used Three ways Method of elimination Immanuel Kant Ontological Argument Can conceive of a perfect being The conceivable is possible Possible a perfect being exists If PB exists, then has all perfections Existence is a perfection If PB exists, then it has existence Possible that a PB necessarily exists Absurd Thus a perfect being must exist of necessity Kant’s First Refutation of the Ontological Argument Concept of God includes concept of absolutely necessary being Compares to nature of a triangle Does not show triangles exist If God, then being exists necessarily-deniable. Cannot go from concept to existence. Immanuel Kant Second Refutation of the Ontological Argument Existence is not a predicate Existence is not a property that adds to the concept of X If existence is not a property, then it cannot be an essential part of God’s concept Merchant analogy The Cosmological Argument A necessarily existing first cause Assumes the principle that everything has a cause The principle only applies to the realm of experience Defects of the ontological argument The Teleologicial Argument Intelligent designer Praise Design imposed on pre-existing matter Need for cosmological argument Immanuel Kant Conclusion Attempts to prove God’s existence are fruitless Impossible to prove God does not exist Theist and Atheist cannot know Possibility of basing religion on practical or moral faith “To deny knowledge in order to make room for faith.” Blaise Pascal Background Life 1623-1662 Contributions Major Works Lettres Provinciales Pensees Pascal’s Wager Part One God God cannot be known Do not know God’s nature or existence Existence is known through faith If God exists, He is infinitely incomprehensible No parts or limits, so no affinity to us Incapable of knowing if or what He is Dare not undertake God’s Existence Cannot be Proven Christians cannot be blamed If the proved it Objection The Wager God is or He is not Reason can decide nothing here What to Wager? Pascal’s Wager Choice Which to Chose Two things to lose: true, good Two things at stake: reason & will, knowledge & happiness Two things to shun: error & misery Must choose Wager for God Don’t Reprove Blame Must wager Weigh gain and loss If gain, gain all If lose, lose nothing Wager that He is Objection & Reply Perhaps one wagers too much Equal risk, 2 lives 3 lives to gain Pascal’s Wager Eternity of life & happiness Infinity of chances, wager 1 to win 2 1 against 3, 1 in infinity, infinity of infinitely happy life There is What you stake is finite Give all Renounce reason Uncertainty Useless to say Uncertain gain Certain risk Infinite distance Not so: staking a certainty against an uncertainty Not an infinite distance Infinity between certainty of gain and certainty of loss Uncertainty of gain proportioned to certainty of stake Pascal’s Wager Risks If equal risks, then play even Certainty of stake = uncertainty of gain Proposition has infinite force Demonstrable How to Make Yourself Believe Seeing the cards Believing Force to wager Learn inability to believe Attain faith Learn Follow Lessen passions Concerns Regarding Pascal’s Wager Disjunction The disjunction False dilemma/many gods False dilemma Options Knowledge of God Lack of knowledge Need the wager Problem If we cannot know God, we cannot know how He will react Payoff and loss cannot be known No rational way to bet Ethics Abandoning reason Ethics