Verbal and Visual Communication—Ekphrasis

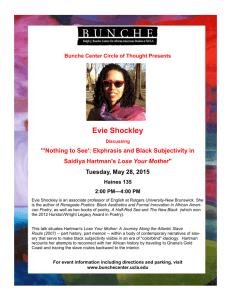

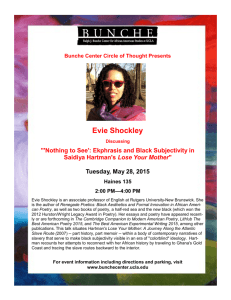

advertisement

Verbal and Visual Communication— Ekphrasis Laura M. Sager Eidt, ”Toward a Definition of Ekphrasis in Literature and Film” in Writing and Filming the Painting: Ekphrasis in Literature and Film The shield produced by Hephaestus described in the Iliad, Book 18 by Homer The first thing he created was a huge and sturdy shield, all wonderfully crafted. Around its outer edge, he fixed a triple rim, glittering in the light, attaching to it a silver carrying strap. The shield had five layers. On the outer one, with his great skill he fashioned many rich designs. There he hammered out the earth, the heavens, the sea, the untiring sun, the moon at the full, along with every constellation which crowns the heavens— the Pleiades, the Hyades, mighty Orion, and the Bear, which some people call the Wain, always circling in the same position, watching Orion, the only stars that never bathe in Ocean stream. The shield produced by Hephaestus described in the Iliad, Book 18 by Homer Then he created two splendid cities of mortal men. In one, there were feasts and weddings. By the light of blazing torches, people were leading the brides out from their homes and through the town to loud music of the bridal song. There were young lads dancing, whirling to the constant tunes of flutes and lyres, while all the women stood beside their doors, staring in admiration. Historical overview of the verbal visual paragone (~ comparison, debate) Plato (424-348 BC) • inferiority of words to images (regarding the mimetic faithfulness of representation). Aristotle (384-322 BC) • parallel between poetry and painting: both imitate human nature in action but with different means (11) Augustine (354-430 AD) • greater difficulty of receiving poetry → it is more valuable than painting • writing encompasses the spiritual more effectively → greater moral and religious value → devaluation of painting (it is absent from the seven liberal arts in 5th century AD) Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) (Della Pittura, 1435) • reasserts the painter’s primacy (the painter excites imagination) (12) Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) • reclaimed the prominent place of the visual arts → to prove the superiority of the visual (Gotthold Ephraim) Lessing (1729-1781) (Laokoon, 1766) • Attempts to reverse the hierarchy by strictly distinguishing the representational realms of poetry and painting • Poetry: best suited to represent actions in time (temporal nature of its reception). • Painting: represents a single pregnant moment in space (perceived as a static object). • Strongly opposes to ekphrasis (it mingles painting and poetry) Definitions of ekphrasis I—the aesthetic approach/paragone • Generally, it refers to works of poetry and prose that talk about or incorporate visual works of art. (9) → verbal to visual • Verbal discourses that directly verbalize one or more visual images. (9) • As a rhetorical device defined in terms of its effect on an audience: as ”expository speech which vividly brings the subject before our eyes” (Theon [335-405] qtd. in Seidt 11). Definitions of ekphrasis II—the aesthetic approach/paragone Murray Krieger: • a device to ”interrupt the temporality of discourse, to freeze it during its indulgence in spatial exploration” (12) • Ekphrastic principle: poems that seek to emulate the pictorial or sculptural arts by achieving a kind of spatiality. → for the Greeks it implied a visual impact on the mind’s eye of the listener → today it renders a visual object into words (12-3) • Ekphrasis today is verbal representation of a visual representation. (13) Leo Spitzer: • ”the poetic description of a pictorial or sculptural work of art, which description implies [...] the production through the medium of words of sensuously perceptible objets d’art [...]”. Wendy Steiner: • a description of a ”pregnant moment in paintings,” an attempt to imitate the visual arts by describing a still moment and thereby halting time (13-4). Definitions of ekphrasis III—the ideological approach/paragone • From the late 80s as a social and ideological struggle – the opposing terms have different ideological roles (14) Ernest B. Gilman: • ”if the image lurks in the heart of language as its unspeakable other, then [...] images harbor a similarly charged connection with language—as an invisible other” (14). Grant F. Scott: • Ekphrasis is the appropriation of the ”visual other” and as an attempt to ”transform and master the image by inscribing it” (14) Definitions of ekphrasis III—the ideological approach/paragone: the implications • • • • What are the implications of such claims or formulations? hierarchy of the verbal and the visual media power relations It is a means of demonstrating dominance and power. (15) W. J. T. Mitchell and James Heffernan: • Ekphrastic texts project the visual as ”other to language”. What does the other (or Other) imply? Bernhard F. Scholz: • The concept of ekphrasis refers to a range of practices rather than to a distinct corpus or genre of texts. What does ”practice” signify here? The excess of definitions • As a rhetorical figure: (15) → in terms of its effect on the listener • As a rhetorical exercise: → as a term for a (descriptive) genre studied in terms of composition and subject matter (15-6) • As a literary genre: (16) → defined by reference to form and/or subject matter • A macrostructure: → defined in syntactic terms (e. g. plot or collage) • As an intertextual relation: → defined by its characteristic relation to another text • As a mode of writing: → to be contrasted with ‘description,’ ‘argumentation,’ or ‘dialogue’ Expanding the definition of ekphrasis Claus Clüver: • the verbalisation of real or fictitious texts composed in a non-verbal sign system (17) Sigling Bruhn: • The representation in one medium of a real or fictitious text composed in another medium (17) → visual representation of a verbal representation (18) vs verbal representation of a visual representation (cf. Heffernan’s definition 13) Laura M. Sager Eidt: • the verbalisation, quotation or dramatization of real or fictitious texts composed in another sign system (19) Visual Ekphrasis: Thomas Struth, Galleria dell’Accademia I, Venedig [Venice], 1992 (184.5 x 228.3 cm) Visual Ekphrasis: Thomas Struth, Kunsthistorisches Museum III, Wien [Vienna], 1989 (187 x 145 cm)