Goal #3: Crisis, Civil War and Reconstruction (1848

advertisement

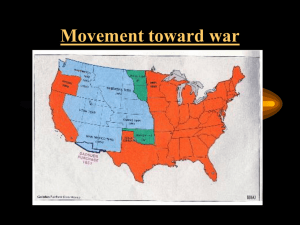

Goal #3: Crisis, Civil War and Reconstruction (1848-1877), analyze the issues that led to the Civil War, the effects of the war, and the impact of Reconstruction on the nation Part I: A House Dividing 3.01 Trace the economic, social, and political events from the Mexican War to the outbreak of the Civil War 3.02 Analyze and assess the causes of the Civil War “To own a pow'r above themselves Their haughty pride disdains; And, therefore, in their stubborn mind No thought of God remains.” From David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored People of the World The Civil War: The U.S. Civil War goes by many names and what you call it shows your interpretation of it: (1) the War of the Rebellion – is its official name on U.S. documents and signifies a view that the South illegally rebelled against the United States (2) the War Between the States – the least politicized view, and the least grammatical unless we understand it to mean the United States against the Confederate States of America (3) the War of Northern Aggression – the strong Southern states’ rights view. All three names, however, do relate to the cause of the war: a breakdown on the question of federalism – whether important economic and social issues would be answered on the national level or on the state level. All three avoid the most important economic and social issue that caused the breakdown: slavery Slavery caused the war in two ways: (1) Americans could not find a compromise on whether slavery should be extended into new territories (2) Americans split over whether slavery should exist at all, causing national institutions to divide along sectional lines (first churches, then political parties, and finally government). But slavery was not the “cause” (or purpose) of the war; neither side at the start of the war was fighting about slavery. Northerners were fighting for union. Southerners were fighting for a looser idea of union, where most authority resided in the states; a view akin to the Anti -Federalist argument in the 1780s. Only after two years of fighting did the war become a war to end slavery. From then on, the Civil War a transformational conflict that fundamentally changed the Constitutional debate over federalism, not to mention human rights. Sectionalism: The idea that the U.S. was less a united nation of similar culture, economy, and politics, than it was a loose federation of unique sections. Historians have debated how to divide the U.S. before the Civil War, but they agree that the nation was not really one united people. Abolitionism: Beginning in the 1830s, it called for elimination of slavery everywhere. Anti-Slavery, “Free Soil”: The view of opponents of slavery who argued that slavery may legally continue to exist where it already exists (i.e. the South), but that it should not be expanded into the new territories: the view of the Free Soil and Republican parties. Pro-Slavery: View of supporters of slavery who argued that slavery was superior to the wage labor system in the North and was a “positive good” that benefited blacks and should be expanded into the new territories. Necessary Evil: Majority view of Southerners toward slavery – that it was bad, but was economically and socially necessary. Missouri Compromise (1820): First in a series of compromises over the extension of slavery into the western territories. Fashioned by Henry Clay, it (1) admitted Missouri as a slave state and (2) created Maine out of Massachusetts as a free state—thereby keeping an equal balance between free and slave states; and (3) drew a line along latitude 36:30 from the Mississippi to the Mexican territory dividing the region into free and slave territories: no slavery north of the line (except in Missouri). Liberia: In 1821, the American Colonization Society (which included James Madison, POTUS at the time-James Monroe, Henry Clay, and John Marshall) bought land from tribal chiefs in West Africa for the purpose of beginning a colony of freed-slaves. In 1822, the first freed slaves arrived and by the 1840s, the colony became the independent country of Liberia with the capital of Monrovia. Only a few thousand slaves ever went to Africa by 1860. Appeal to the Colored People of the World (1829): Pamphlet by David Walker, a free black from Ohio, it called for slaves to rise-up in violent insurrection against the whites. Nat Turner: Slave who led a rebellion against whites in Southampton County, Virginia, in 1831. At least 60 whites were killed in the uprising. The slaves, including Turner, were captured and hanged. The rebellion caused southern states to tighten control on slaves through stricter Slave Codes. William Lloyd Garrison: Leading abolitionist, he began publishing The Liberator in Boston in 1831. The radical abolitionist newspaper threatened southerners: “Let Southern oppressors tremble,” it declared, “let all the enemies of the persecuted blacks tremble.” Garrison insisted he would do what was necessary to bring an end to slavery: “I am in earnest -- I will not equivocate -- I will not excuse -- I will not retreat a single inch,” and most famously he declared, “AND I WILL BE HEARD.” Garrison became a key voice of abolitionism in the North Frederick Douglass: Slave who escaped from a plantation in Maryland and fled north to Rochester, NY. In 1845, he published his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, and began an abolitionist newspaper, entitled North Star -- a reference to what the slaves should follow to freedom. During the war, he met with President Lincoln to urge him to make the war about slavery and to urge him to emancipate the slaves. Underground Railroad: Secret network set up by opponents of slavery to enable runaway slaves to hide in private homes on their way to freedom in the North or Canada. One of the most famous conductors in the railway was an escaped slave, Harriet Tubman Gag Rule: Showing how deeply divided the sections were on the issues of slavery and abolition, the House of Representatives in 1837 passed the gag rule that prohibited any debate and tabled all “petitions, memorials, and papers touching the abolition of slavery, or the buying, selling, or transferring of slaves, in any State, District, or Territory, of the United States.” The Great American Schism: Schism means division and usually refers to a break between factions of a church. Churches were one of the few truly national institutions in the U.S. during the first half of the nineteenth century. Beginning in the early 1840s, largely as a result of the heightened desire to eliminate sin in the nation and bring on the new millennium, the mainline Protestant churches split on sectional lines over the issue of slavery. In 1844, the Methodist Episcopal Church divided into northern and southern branches. The national Baptist church tried to keep a neutral stance on slavery, but tensions arose when Northerners refused to appoint as missionaries anyone who owned slaves. In 1845, delegates from Southern churches met in Augusta, Georgia, to form the Southern Baptist Convention. Other denominations also fractured. Although the Presbyterians did not formally split until 1861, racial lines were drawn in that church as early as 1837. Wilmot Proviso (1846-1850): Despite the gag rule, David Wilmot (D-PA) offered a resolution ordering that slavery would be excluded from all territories gained in the Mexican War. The resolution was attached as a rider on numerous bills between 1846 and the Compromise of 1850, goading the Southern legislators. It passed the House but not the Senate. It represented a growing opposition to slavery and a strengthening of the “Anti-Slavery” position in Congress. The Great Debate: The Thirty-First Congress was among the most dramatic in U.S. history. In the Senate, it marked the last performances of the Great Triumvirate of Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster. It included other influential representatives such as Sam Houston of Texas, It included some leaders of the new generation of “Young Americans,” such as: future Presidential candidate Stephen A. Douglas, future Secretary of State William H. Seward, future Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, and future President of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis. The Congress also faced some of the most serious issues of any--what to do with the lands of the Mexican Cession and how to reconcile the growing tension over slavery. Compromise of 1850: Agreement on how to organize territories gained in the Mexican War; major provisions were (1) admission of California as a free state; (2) assumption of the Texas debt; (3) abolition of the slave trade in D.C.; (4) strengthening of the Fugitive Slave laws. It was the last act of Henry Clay, the Great Compromiser, but it owed its enactment to Stephen A. Douglas (D-IL). Fugitive Slave Act: Part of the Compromise of 1850, it ordered Northerners to return runaway slaves; provided bounties for slavecatchers; ordered civilians to help capture runaway slaves; denied fugitive slaves the right to speak in their defense in court; and denied them a jury trial. As a consequence some free blacks were put in bondage. The law outraged northerners. The fugitive slave issue shows the South’s desire for a strong national government when it benefited the region. “So you’re the little lady who caused this great war. . .” Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, it tells story of slaves—Eva, Eliza and Uncle Tom—and their suffering under slavery. It became a huge bestseller, advancing the cause of abolitionism. Stephen A. Douglas: From Illinois, he became a Democratic leader of the new generation of politicians called the Young Guard (or Young America) that came to office after the Mexican War. He was known as the Little Giant because he was only 5’4” but a powerhouse in the Senate. He conceived the tactic by which Clay’s Compromise of 1850 passed Congress. He later became a leader of the party. He ran against Abraham Lincoln in the 1858 Senate race in Illinois. The two had a series of important debates over slavery and politics. Douglas beat Lincoln for the Senate, but lost to him in the 1860 Presidential election Popular Sovereignty: Policy associated with Senator Lewis Cass (D-MI) and Stephen A. Douglas. It tied into the federalism debate, saying that on controversial issues such as slavery, decisions should be made on the local territorial level not by Congress: people living in a territory should be allowed to have slavery if they want it, regardless of the Missouri Compromise. It led to a power vacuum in Kansas and “Bleeding Kansas,” a violent conflict between those who wanted slavery and those who did not Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854): Law that eliminated the agreement established in the Missouri Compromise that Congress could regulate slavery in the territories; it upheld popular sovereignty saying: “all questions pertaining to slavery in the Territories and in the new states . . . are to be left to the people residing therein.” As an aside, it also marked the death of the Whig Party. Republican Party: With the death of the Whig Party, anti-slavery advocates created several small parties some of which grew into a new political party to oppose the Democrats. The Republican party believed that “Free Soil” and “Free Labor” would lead to “Free Men” (i.e. a freer and more prosperous society). The 1st presidential candidate of the party (1856) was John C. Fremont. A regional (northern) party, the Republicans lost to popular sovereignty candidate, James Buchanan. “Bleeding Kansas”: As a result of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, abolitionists and supporters of slavery raced to Kansas to see who could establish a territorial government. Throughout 1856, the two sides clashed in violent conflict, leading to the “sack of Lawrence” and the Pottawatomie Massacre. By the end of the year about 200 people had been killed and there was more than $2 million property damage done “Tragic Prelude I,” by John Steuart Curry "Bully" Brooks: Sectional violence reached Congress in May 1856. In a speech, Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts attacked the pro-slavery violence in Kansas and singled out Senator A.P. Butler of South Carolina for rebuke, calling him a liar, among other things. Butler chose to ignore the insult, but the Senator's nephew, Congressman Preston Brooks, would not. Brooks went to the Senate and found Sumner at his desk. He accused Sumner of libeling the South and proceeded to beat him severely about the head with his cane. Sumner did not return to the Senate for two years. The House of Representatives censured Brooks, but when he returned to South Carolina the people re-elected him to Congress. As he left to return to Washington, they showered him with gifts of new canes. Lecompton Constitution: By mid-1856, the proslavery legislature in Kansas called a constitutional convention to earn statehood. The convention in Lecompton drew up a constitution making Kansas a slave state. President James Buchanan supported the Lecompton Constitution and demanded that the Senate accept it. Before the Senate acted, Kansas re-voted and antislavery forces overwhelmingly rejected it again, ending the conflict over slavery in Kansas. The Kansas issue split the Democratic Party over the issue of popular sovereignty. Because of Buchanan’s positive response to the Dred Scott ruling and his actions in the Kansas controversy, both of which helped cause the Civil War, historians rank him last among men who have served in the office of the Presidency. Dred Scott Case: 1857 Supreme Court decision (written by Chief Justice Roger Taney) that intensified the hostility between abolitionists and pro-slavery factions. It involved the freedom of Dred Scott, a slave from Missouri who had been transported by his owner to Wisconsin and was kidnapped by abolitionists while returning to Missouri. You will recall that under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, slavery was prohibited in territories above the Ohio River. The Court ruled: (1) that Scott was the property of his master and would remain so until his master decided to free him (2) that blacks were not citizens under the Constitution, thereby erasing all rights of free blacks and slaves alike (3) that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, eliminating Congress as a factor in the conflict over the extension of slavery into the territories. Lincoln-Douglas Debates: The Freeport Doctrine (1858) Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas ran against each other in 1858 to be U.S. Senator from Illinois. The debated across the state, including in Freeport where, to the question can the people of a Territory exclude slavery, Douglas asserted popular sovereignty. Douglas: The next question propounded to me by Mr. Lincoln is, can the people of a Territory in any lawful way, against the wishes of any citizen of the United States, exclude slavery from their limits prior to the formation of a State Constitution? I answer emphatically, . . . that in my opinion the people of a Territory can, by lawful means, exclude slavery from their limits prior to the formation of a State Constitution. . . . It matters not what way the Supreme Court may hereafter decide . . . the people have the lawful means to introduce it or exclude it as they please, for the reason that slavery cannot exist a day or an hour anywhere, unless it is supported by local police regulations. (Right, right.) Those police regulations can only be established by the local legislature, and if the people are opposed to slavery they will elect representatives to that body who will by unfriendly legislation effectually prevent the introduction of it into their midst. If, on the contrary, they are for it, their legislation will favor its extension. The statement would cost Douglas the South in the election of 1860. John Brown: Fanatical abolitionist who led raids during "Bleeding Kansas." In 1859, he tried to arm the slaves for an insurrection by taking the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. U.S. troops under Robert E. Lee captured Brown’s gang. They were tried and hanged. The raid stirred opposition to slavery in the North and struck fear in the hearts of Southerners; southern states organized militias to defend against future attacks. The raid ensured that slavery would be the main issue in the 1860 election. And Brown became a martyr to the cause of abolition. He was remembered in the most famous song of the Civil War era: "John Brown's Body," sung to the tune of Julia Ward Howe's new composition, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic." “John Brown’s Body” Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord; He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored; He has loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword; His truth is marching on. Chorus: Glory! Glory! Hallelujah! Glory! Glory! Hallelujah! Glory! Glory! Hallelujah! His truth is marching on. I have seen Him in the watch fires of a hundred circling camps They have build Him an altar in the evening dew and damp; I can read His righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps; His day is marching on. John Brown's body lies a-mold'ring in the grave John Brown's body lies a-mold'ring in the grave John Brown's body lies a-mold'ring in the grave But his soul goes marching on He has gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord He has gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord He has gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord His soul is marching on He captured Harper's Ferry with his nineteen men so true He frightened old Virginia till she trembled through and through They hung him for a traitor, themselves the traitor crew His soul is marching on Abraham Lincoln, 1809-1865: 1860 Republican presidential candidate, Lincoln was a Whig Congressman representing Springfield, Illinois, in the 1840s, and lost the campaign against Stephen Douglas for U.S. Senator from Illinois in 1858, after a series of important debates. He opposed the expansion of slavery. Several Republicans ran for the party’s nomination in 1860, but an important speech at Cooper Union in New York City put Lincoln in the lead. Lincoln won the election because slavery had split the Democratic party into Northern and Southern wings. His election prompted states in the Deep South to secede from the Union, starting with South Carolina. With secession came war. The prospect of war caused the Upper South to secede. Lincoln refused to acknowledge the South's right to secede and fought to restore the Union. As President, Lincoln was consumed by the War. Often frustrated that his military leaders seemed unable or unwilling to take the battle to the Confederates and win, he replaced general after general until he found one he liked in the person of Ulysses S. Grant. Always interested in the politics of an issue, he delayed a move to emancipate the slaves (or to focus on ending slavery as a war aim) until there was no alternative but to face the fact that the war really was about slavery all along. Victories in Gettysburg and Vicksburg turned the war in the Union's favor, but it would be nearly two years before the Confederacy gave up. Before the surrender, Lincoln delivered his most eloquent expression on the purpose of the war and on liberty and democracy (the Gettysburg Address). He also had to get reelected in 1864, a feat that looked impossible in the summer of that year. When he was re-elected, he turned his attention to how the Union should be restored. In his Inaugural Address in 1865, he declared his vision. His moderate, compassionate design of "malice toward none and charity for all" would not be given a chance to see fruition. On April 14th, 1865, just days after celebrating the Confederate surrender, he was murdered by John Wilkes Booth. His execution of and winning of the war to restore the Union and to end slavery made him the greatest President of the United States. Lincoln on Slavery and The Union: Lincoln, remarks on Jefferson, April 6, 1859 “The principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society. [Those who deny them] are the vanguard, the miners and sappers of returning despotism. We must repulse them, or they will subjugate us. . . . [He] who would be no slave must consent to have no slave. Those who deny freedom to others deserve it not themselves, and, under a just God, cannot long retain it. Lincoln to Alexander Stephens, Vice-President of the Confederacy, December 11, 1860 “I fully appreciate the present peril the country is in, and the weight of responsibility on me. Do the people of the South really entertain fears that a Republican administration would, directly or indirectly, interfere with the slaves, or with them about the slaves? If they do, I wish to assure you, as once a friend, and still, I hope, not an enemy, that there is no cause for such fears. . . . I supposed, however, this does not meet the case. You think slavery is right and ought to be extended, while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. That, I suppose, is the rub. [It is] the only substantial difference between us.” Lincoln to Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, August 20, 1862 “As to the policy I ‘seem to be pursuing,’ as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt. I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. . . . My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the coloured race, I do because I believe it helps the Union.” Lincoln to Gen. James Wadsworth, January or February 1864 “. . . in the event of our complete success in the field, the same being followed by a loyal and cheerful submission on the part of the South . . . I cannot see, if universal amnesty is granted, how, under the circumstances, I can avoid exacting in return universal suffrage [for the Freedmen]. . . . How to better the condition of the coloured race has long been a study which has attracted my serious and careful attention; hence I think I am clear and decided [that] in assisting to save the life of the Republic they have demonstrated in blood their right to the ballot, which is but the humane protection of the flag they have so fearlessly defended.” Lincoln to A.G. Hodges, April 4, 1864 “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think and feel, and yet I have never understood that the presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling. It was in the oath I took that I would, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution. . . . I could not feel that, to the best of my ability, I had even tried to preserve the Constitution, if, to save slavery or any minor matter, I should permit the wreck of Government, country, and Constitution all together. When, early in the war, Gen. Fremont attempted military emancipation, I forbade it, because I did not think if an indispensable necessity. When, a little later, Gen. Cameron, then Secretary of War, suggested the arming of the blacks, I objected because I did not think it an indispensable necessity. . . . When in March and May and July, 1862, I made earnest and successive appeals to the border states to favour compensated emancipation, I believed the indispensable necessity for military emancipation and arming the blacks would come unless averted by that measure. They declined the proposition, and I was, in my best judgment, driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union, and with it the Constitution, or of laying strong hand upon the coloured element. I chose the latter. . . . In telling this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years’ struggle, the nation’s condition is not what either party, or any man, devised or expected. God alone can claim it. Whither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North, as well as you in the South shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God. Election of 1860: Four major candidates ran for POTUS in 1860: 1. Abraham Lincoln was Republican candidate, supporting free-soil 2. Stephen A. Douglas ran for the northern-wing of the Democratic Party, supporting popular sovereignty 3. John C. Breckenridge ran under the banner of the southern, pro-slavery wing of the Democratic Party 4. John Bell as the Constitutional Union Party candidate called for the Constitution to be enforced. With Democrats split, Lincoln won. The certification of Lincoln’s victory prompted the secession of South Carolina. By February, six other states, all in the Lower South, seceded, meeting in Montgomery, Alabama, to form the Confederate States of America. The Upper South seceded after Lincoln’s inauguration and the first shots at Fort Sumter Crittenden Compromise: Last ditch effort in Congress solve the constitutional crisis and avoid war – it was led by Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky. It called for (1) the Missouri Compromise line to be reinstated and extended to the California border and (2) for a constitutional amendment to protect slavery where it existed. The Republicans, including Lincoln, were willing to accept the amendment, but would not go back on their commitment to “free soil.” Lincoln’s inauguration and the battle at Fort Sumter made the proposal moot. And the war came …