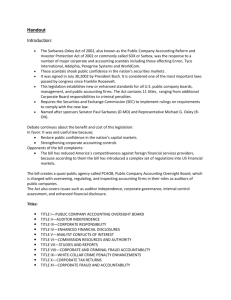

HSS-SECNegative - SpartanDebateInstitute

advertisement