Bioterrorism:

advertisement

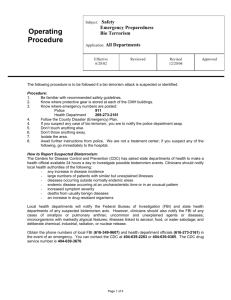

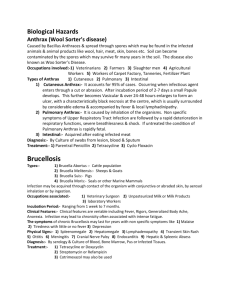

Bioterrorism: Are Physician Assistants Prepared to Diagnose and Treat? Mark Bostic Spring 2006 PAS 646 Objectives 1) Talk about PA preparedness 2) Talk about bioterroristic diseases What is bioterrorism? Form of terrorism in which biological agents are used to inflict harm and/or fear upon a population. http://www.fbi.gov/anthrax/images.htm#1 Physician Assistant Training Medical school model Consistent with physician training Bioterrorism? Bioterrorism Training Physician Assistant Programs’ Websites – Accreditation Review Commission on Physician Assistant Programs (ARC-PA) – No training specified No training mandated Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) – No training mandated Physician Assistant Preparedness Studies lacking for PA’s Physician preparedness – HHS Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) survey indicates physicians unprepared – n=614 physicians, 18% trained, 93% expressed interest Johns Hopkins University study indicates physicians unprepared n=2407 physicians, pretest 46.8%, posttest 79% Chickenpox vs. smallpox, botulism vs. Guillain-Barre CDC top six bioterroristic agents Anthrax Smallpox Plague Viral hemorrhagic fevers Botulism Tularemia Anthrax Bacillus anthracis – Spore-forming bacterium Livestock, meat products, wool sorters Inhalational, cutaneous, gastrointestinal Often misdiagnosed as influenza Inhalational anthrax Most deadly Incubation period Replication and toxin release Phase I: nonspecific constitutional symptoms – Mild fever, malaise, myalgia, nonproductive cough, emesis, chest/abdominal pain Phase II: more severe – Higher fever, chest/neck edema, mediastinal widening, dyspnea, cyanosis, meningoencephalitis, shock Diagnosis: inhalational anthrax Chest x-ray and chest CT – Blood smear and gram stain/culture – – Mediastinal widening, pleural effusion, consolidation Large bacilli Left shift Cerebrospinal Fluid – Purulence, decr. glucose, incr. protein, elevated pressure, blood Inhalational anthrax www.cdc.gov Cutaneous anthrax Most prevalent form of infection Skin barrier must be compromised Replication and toxin release – May take up to 14 days Diagnosis: cutaneous anthrax 1) pruritic papule or pustule surrounded by smaller vesicles 2) mild fever and malaise 3) papule enlarges to a circular lesion surrounded by edema – – Ruptures and necroses Characteristic “Black Eschar” Cutaneous anthrax www.cdc.gov Treatment: anthrax Combination of: – – Combination varies depending upon: – Ciprofloxacin (Cipro ®) Doxycycline (Vibramycin ®) Adult, child, immunocompromised Amoxicillin for pregnant females Smallpox (Variola) DNA virus Transmitted in droplet form Respiratory tract mucosa 12-14 day incubation period Often misdiagnosed as varicella Diagnosis: smallpox Rapid onset of nonspecific sx’s – Fever, HA, malaise, chills, myalgia, anorexia, N/V, diarrhea, abdominal pain, delirium, convulsions Papules surrounded by rash a few days later Centrifugal distribution Papules pustules crusted lesion Simultaneous staging of lesions Not “dewdrops on a rose petal” Smallpox www.cdc.gov Treatment: smallpox No cure Tx is supportive Vaccination available = Vaccinia Plague Yersinia pestis – – Gram negative, pleomorphic coccobacillus Infects by fleas carried by rodents Bubonic, septicemic, pneumonic Diagnosis: bubonic and pneumonic plague Onset of nonspecific sx’s in 2 to 6 days – – – – Fever, chills, weakness, malaise, myalgia, lethargy chest pain, dyspnea, watery/bloody expectorated sputum Tender buboes (swollen lymph nodes) 2 to 4 days later, lung exhibits necrosis, infiltration, hemorrhaging, effusion, abscesses Chest x-ray Hypotension, respiratory distress, pulmonary edema = death in 24 hours Plague www.cdc.gov Diagnosis: septicemic plague Fever, chills, prostration, N/V, abdominal pain Purpura and DIC hypotension, shock, and death Blood cultures (all types of plague) – Gram stain & culture (all types of plague) – Prior to tx with antibiotics Prior to tx with antibiotics Sputum sample Treatment: plague Streptomycin (1st line) Gentamicin (2nd line) Tetracylines such as chloramphenicol Viral hemorrhagic fevers RNA viruses: – Infection via vectors: – Arenavirus, bunyavirus, filovirus, flavivirus Mosquitoes, ticks, cats, rabbits, people History should include travel to tropical regions Diagnosis: VHF Onset of nonspecific symptoms: – – Hallmark: generalized systemic coagulopathy with profuse bleeding – – Fever, HA, myalgia/arthralgia, N/V, diarrhea Possible bradycardia, tachycardia, liver necrosis, delirium, confusion, coma Petechiae, ecchymoses, epistaxis, hematemesis Bleeding from gingiva, vagina, any puncture sites Definitive: immunoglobulin Antibody to specific virus Viral hemorrhagic fevers http://www.gata.edu.tr/dahilibilimler/infeksiyon/resimler/VIRAL_HEMORRHAGIC_FEVER/__VIRAL_HEMORRHAGIC_FEVERS_2.JPG Treatment: VHF No FDA approved drugs Ribavirin may be effective Supportive treatment of shock: – Hydration, blood transfusions, etc. Botulism Spore-forming anaerobic bacterium Clostridium botulinum Toxin is most lethal of all toxins – – 100,000x sarin gas 15,000x nerve gas Iraq: enough to kill every human 3 times Bacterium or toxin may be aerosolized, placed in food supplies Blocks ACh release Diagnosis: botulism Descending paralysis Ptosis, diplopia, blurred vision, and dilated, sluggish pupils Difficulty speaking, chewing, swallowing Paralytic asphyxiation or flaccid airway collapse Culture serum, stool, gastric contents, suspected food Treatment: botulism (cont.) Equine botulinum antiserum Antibiotic therapy experimental – – Metronidazole PCN Supportive: ventilation and tube feeding Tularemia Nonmotile, aerobic gram negative coccobacillus Francisella tularensis – 2 subspecies: biovar tularensis & biovar palaeartica Bite of tick, mosquito, handling infected carcass Aerosolization possible Incubates, then moves to LN and multiplies Pathology at all sites where bacillus spreads Diagnosis: tularemia Site of inoculation: papule-pustule-ulcer pattern Eye: ulceration of conjunctiva with LAD Oral: tonsillitis or pharyngitis with cervical LAD Lungs: bronchiolitis, pneumonitis, pleuropneumonitis with LAD Fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, emesis IF, GS&C Tularemia http://www.logicalimages.com/resourcesBTAgentsTularemia.htm http://phil.cdc.gov/Phil/details.asp Treatment: tularemia Ciprofloxacin or doxycycline (early) Streptomycin or gentamicin (late) No vaccine Reporting Written plan in every health care facility Notify local health care officer for suspected or confirmed cases Conclusion Data suggest that physicians are unprepared to diagnose and manage diseases of a bioterroristic cause. Studies need to be performed to determine whether or not PA’s are prepared. Thank you for your attention! References ARC-PA (2005). “Accreditation standards for physician assistant education.” Section B(1-7): 11-13. CDC (2005). “Agents, diseases, and other threats.” Cited on World Wide Web 1 December 2005 at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/. Cosgrove, S. E., T. M. Perl, X. Song, S. D. Sisson (2005). “Ability of physicians to diagnose and manage illness due to category A bioterrorism agents.” Archives of Internal Medicine 165(17): 2002-2006. Endy, T. P., S. J. Thomas, J. V. Lawler (2005). “History of U.S. Military Contributions To The Study of Viral Hemorragic Fevers.” Military Medicine 170(4): 77-91. Goad, J. A., J. Nguyen (2003). “Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses.” Top Emerg Med 25(1): 66-72. Hickner, J., F. M. Chen (2002). “Survey on Eve of Anthrax Attacks Showed Need for Bioterrorism Training.” Press release 5 September 2002. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Cited on World Wide Web on 22 December 2005 at http://www.ahrq.gov/news/press/pr2002/anthraxpr.htm Karwa, M. (2005). “Bioterrorism: Preparing for the impossible or the improbable.” Critical Care Medicine 33(1 Suppl): S75-95. References LCME (2004). “Functions and structure of a medical school.” Section II(A): 2. Leger, M. M., R. McNellis, R. Davis, L. Larson, R. Muma, T. Quigley, S. Toth (2001). “Biological and chemical terrorism: Are we clinicians ready?” American academy of physician assistants. Cited on world wide web 3 January 2005 at http://www.aapa.org/ clinissues/BTtext.htm. Lohenry, K. (2004). “Anthrax exposure – stay alert, act swiftly” Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants 17(8): 29-33. NPR online, (2005). “History of Biological Warfare.” Cited on World Wide Web 21 November 2005 at http://www.npr.org/news/specials/response/anthrax/features/2001/ oct/011018.bioterrorism.history.html. O’Brien, K., M. Higdon, J. Halverson (2003). “Recognition and Management of Bioterrorism Infections.” American Family Physician 67(9): 1927-34. Straight, T. M., A. A. Lazarus, C. F. Decker (2002). “Defending Against Viruses in Biowarfare.” Postgraduate Medicine 112(2): 75-80. References Varkey, P., G. Poland, F. Cockerill, T. Smith, P. Hagen (2002). “Confronting Bioterrorism: Physicians on the Front Line.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 77(7): 661-72. United States Department of Health and Human Services (2002). “HHS announces $1.1 billion in funding to states for bioterrorism preparedness.” HHS press release 31 January 2002. Cited on World Wide Web 30 December 2005 at http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/ 2002pres/20020131b.html.