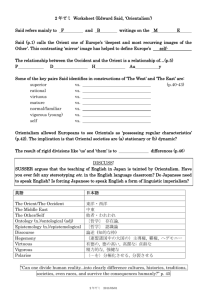

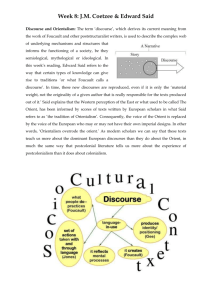

Dina El-Kassaby - AUC DAR Home - The American University in Cairo

advertisement