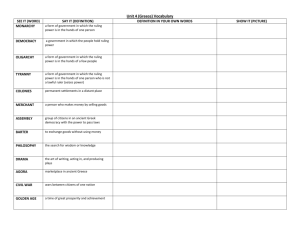

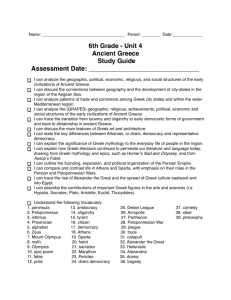

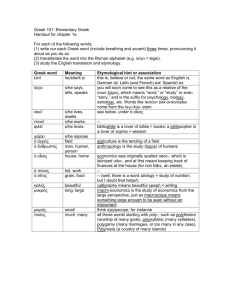

Athens 9-10 2014

advertisement