3. Admission and Enrolment Procedure - Faculty of Arts

advertisement

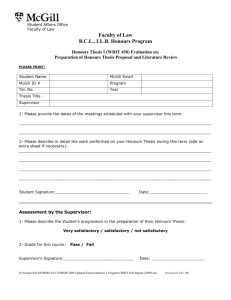

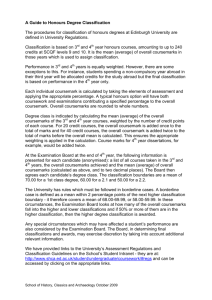

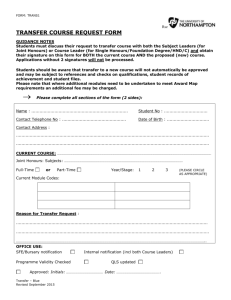

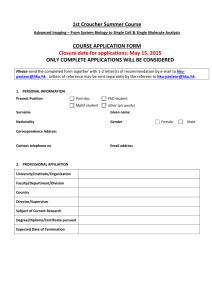

Discipline of Philosophy THE UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE Department of Philosophy FLINDERS UNIVERSITY HONOURS IN PHILOSOPHY 2012 PROGRAM INFORMATION AND HANDBOOK Welcome to Honours in Philosophy! This document gives you information about eligibility for admission into the Honours program for Philosophy in 2012, details of the program of study involved, and the enrolment procedure. It also serves as a handbook providing information about assessment and advice for you to consult during your Honours year. CONTENTS 1. Honours Coordinators 2. Eligibility 3. Admission and Enrolment Procedure Part-Time Enrolment 4. Program Structure 5. Thesis Supervision Thesis Proposal 6. Seminars 7. Study Advice 8. Start-of-Year Meeting 9. Assessment Submission Format Marking Deadlines and Penalties Extensions 10. Degree Classification 11. Admission Form 1. HONOURS COORDINATORS These are the people to consult with questions about any of the topics covered in this handbook: Garrett Cullity University of Adelaide Napier 711, 8303 6375 garrett.cullity@adelaide.edu.au Lina Eriksson Flinders University Humanities 267, 8201 2016 lina.eriksson@flinders.edu.au (Please consult the handbook first!) 2. ELIGIBILITY (UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE STUDENTS) To be eligible for admission into the Honours program, you will need to satisfy four conditions: (i) have completed the requirements for a Bachelor degree (ii) have completed a Major sequence of study in Philosophy (24 units including 18 units at Advanced Level) and (iii) have achieved an average of 70% or better in your Philosophy courses (iv) propose a thesis topic for which a staff member of the discipline is willing and able to offer supervision. 3. ADMISSION AND ENROLMENT PROCEDURE In order to enter the Honours program, you need to: (i) be admitted by the Discipline/Department (ii) formally enrol as an Honours candidate with the Faculty. The procedure for admission by the Discipline is to fill out the admission form at the end of this handbook and return it to your Honours Coordinator. You will then be contacted by the Coordinator with confirmation of your acceptance. The Faculty office will then contact you to inform you about your formal enrolment (and payment), which takes place online. PART-TIME ENROLMENT (UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE STUDENTS) At the University of Adelaide it is possible to do Honours over two years (i.e., part-time), but the grounds for granting permission to do this are limited to: (i) students with care-giver responsibilities (ii) students in greater than or equal to half time employment (iii) students with a significant illness or disability (iv) students enrolled for part of the Honours program at an overseas institution (v) compassionate reasons In all circumstances, it should be clear that the student is unable to (rather than chooses not to) pursue the coursework on a full-time basis. Furthermore, part-time requires that the Honours course is completed over two consecutive years. Any student wishing to enrol in Philosophy Honours part-time should consult with the Honours Coordinator at the earliest opportunity, so as to determine eligibility. 4. PROGRAM STRUCTURE The Honours program in Philosophy is run jointly by the Discipline of Philosophy at The University of Adelaide and the Department of Philosophy at The Flinders University of South Australia. The program, which is completed over one year on a full-time basis or two years part-time, comprises 3 semester-length seminars and a thesis. All students must do at least one third of their program (i.e., at least two seminar courses or thesis supervision) in the department in which they are formally enrolled. The arrangements for Joint Honours (i.e., a program of study divided between Philosophy and another subject) will be determined on an individual basis: interested students should contact their Honours Coordinator. 5. THESIS SUPERVISION Students must submit a thesis of length 15,000–18,000 words. Prospective Honours students are asked to see their Honours Coordinator at the earliest opportunity to discuss a thesis topic and supervisor, as it is expected that students will be working on their theses during the summer vacation. At the very latest, Honours students should have arranged both a supervisor and a thesis topic by early February (or late August for students commencing in second semester). Your supervisor has responsibility for meeting you regularly throughout the year to supervise your thesis work. The frequency and duration of your meetings with your supervisor should be established by mutual agreement. If students wish to receive comments on a full draft of their thesis, they should submit it to their supervisor six weeks prior to the submission deadline. After this date, supervisors may have difficulty in providing timely feedback. The content of the thesis must be significantly different from the content of any other work submitted for assessment as part of the Honours program. THESIS PROPOSAL Students must submit to their supervisor a thesis proposal of approximately 1000 words. Due dates for the thesis proposal are 16 March 2012 and 21 September 2012 for students commencing in first semester or second semester, respectively. The thesis proposal is an initial description of the ground you intend to cover in your thesis. It should be developed in consultation with your supervisor, and should demonstrate extensive reading and include a bibliography. This proposal will provide you with a framework to guide your ongoing thesis work. (However, the proposal is not part of the formal assessment of your thesis, and it is possible for your thesis to depart from it as it develops.) 6. SEMINARS Honours students complete three semester-length seminars. The list of seminar offerings for 2012 is given below. The seminars are divided into two groups: Epistemology & Metaphysics (E&M), and Moral & Social Philosophy (M&S). All Honours students must take at least one seminar from each group. Each of the seminars meets for two hours per week during teaching weeks for the duration of the semester (time and place to be advised). As part of the assessment requirements for each seminar, students must make at least one in-class presentation during the course of the semester, which can serve as an essay plan or draft. Each seminar is assessed by one essay of 5,000-6,000 words in length. SEMINAR LIST The following list of seminars is offered subject to availability. (If there are insufficient enrolments, seminars on this list may be withdrawn.) SEMESTER 1 SEMESTER 2 Kant’s Ethics (M&S) Denise Gamble, Garrett Cullity Adelaide Time and Space (E&M) Graham Nerlich Adelaide Self-Knowledge (E&M) Jordi Fernandez Adelaide Meaning and Mental Representation (E&M) Jon Opie Adelaide The Evolution of Cooperation (M&S) Lina Eriksson Flinders Emotions and Ethics (E&M/M&S) Ian Ravenscroft Flinders Ethics and Literature (M&S) Craig Taylor Flinders COURSE DESCRIPTIONS KANT’S ETHICS Semester 1, M&S Denise Gamble and Garrett Cullity In this course, we will examine the ethical theory of Immanuel Kant. The emphasis will be on trying to understand Kant's three great ethical works -Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, Critique of Practical Reason, and The Metaphysics of Morals -- with some help from the secondary literature. The Groundwork will be read in its entirety, and we will study selections from the other two works. The course will have the aims of critically examining the overall structure of Kant's ethical thought, assessing its plausibility, and trying to appreciate why it is regarded as making such a significant contribution to Western moral philosophy. In the first half of the course, we will examine the two foundational works (Groundwork and CPR), with a view to understanding what kind of foundation Kant claims for morality, and what kind of arguments he thinks can establish that foundation. In the second half, we will turn to the details of the ethical system he builds on this foundation in his later work The Metaphysics of Morals, paying particular attention to Kant's account of virtue. Preliminary reading: It will be assumed that students have read the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals before the course commences. SELF-KNOWLEDGE: PERSPECTIVES FROM PHILOSOPHY AND COGNITIVE SCIENCE Semester 1, E&M Jordi Fernandez In philosophy, it is widely believed that people have a special access to their own thoughts. Philosophical discussions of self-knowledge typically start from a statement of this fact, and proceed to develop theories that are aimed at explaining it. Recently, though, there has been a range of evidence from cognitive science that has put pressure on the philosophical notion that we know our own thoughts in a special way. The relevant evidence comes from experimental studies in social psychology, through introspection-sampling studies, studies of systematic failures of self-knowledge in schizophrenia, as well as brain-imaging data for self versus other tasks. In this course, we will (1) consider different theories of self-knowledge, and what makes self-knowledge interesting, and (2) we will review the justmentioned evidence from cognitive science, and discuss its significance for the philosophical thesis that we have a special access to our own thoughts. Preliminary reading: Peter Carruthers, The Opacity of Mind: an integrative theory of self- knowledge (OUP, 2011). THE EVOLUTION OF COOPERATION AND HELPING BEHAVIOUR Semester 1, M&S Evolution benefits behaviour that is conducive to having more – and reproducing – offspring than others have. It is thus a competitive process, and as a result, it seems evolution would generally generate self-interested behaviour. After all, helping others do not benefit you and your offspring. And yet, we know that human beings are capable of cooperation and of altruistic acts. How can this be? To answer this puzzling question, we will look at the main suggestions as to what drives the evolution of pro-social behaviour, cooperative as well as altruistic: kin selection, reciprocity, selection of mates, and group selection. Much of the basic discussion will be based on basic game theory, in particular the Prisoners’ Dilemma game and the Stag Hunt and other social dilemmas. These games illustrate the problem of how self-interested behaviour can be better in the short-term but worse in the long-term, and what conditions have to be fulfilled for pro-social behaviour to be likely to result in good outcomes also for the people who, it seems, sacrifice some of their own good for others. The preliminary readings are two key books presenting the basic game theory foundation for the analysis of cooperative behaviour: Axelrod’s pathbreaking book on successful strategies in Prisoners’ Dilemma games – aptly named The Evolution of Cooperation - and Brian Skyrms’ famous book The Stag Hunt and Evolution of Social Structure. We will complement this literature with journal articles and book chapters on kin selection, reciprocity, the selection of mates, and the controversial notion of group selection, by, among others, Samir Okasha, Elliot Sober and David Sloane Wilson, and Alexander Rosenberg. Preliminary reading: Axelrod, Robert (1984), The Evolution of Cooperation Skyrms, Brian. (2004) The Stag Hunt and Evolution of Social Structure. TIME AND SPACE Semester 2, E&M Graham Nerlich This course will be based on a single book: Barry Dainton, Time and Space Acumen 2nd edition 2010. Time and space are somehow very familiar indeed. Every perception happens sometime and almost all of them are perception of things in space and time. They pervade every action too. But both are deeply puzzling. Especially time is. St Augustine said [roughly] “If no one asks me what time is, I know. But if someone asks me I can’t say”. Are space and time real? Is space simply nothing? Does time flow? Can you travel in time? These questions come at the beginning of any systematic thinking about these concepts. Most thought about space has ignored geometries other than Euclid’s. It is easy enough to see the importance of this oversight by considering spaces of just 2 dimensions. These can be drawn or modelled and their 3-D analogues pretty well understood from the simpler spaces. Space and time will be given equal attention in the course. Dainton’s book is an excellent introduction to the challenges of this area of metaphysics. It is written at a standard ideal for an Honours course. There is some physics in the book but we will avoid almost all of that and also the more technical analysis of Zeno’s paradoxes. However, anyone interested in the topic should put in some time on the Special Theory of Relativity. That will not be compulsory, but I will give a couple of hours, over and above what’s scheduled for the course, teaching it for those who would like it. It can be learnt without any maths. MEANING AND MENTAL REPRESENTATION Semester 2, E&M Jon Opie Mental representation has been somewhat on the nose, of late. There have been a number of recent attempts to envisage a science of the mind without this foundational concept. We will buck the trend, examining various accounts of mental representation and its role in cognition, with a view to defending representationalism against the naysayers. Your mission, if you accept it: to decide if philosophy can do without mental representation. Preliminary reading: Cummins, R. (1991) Meaning and Mental Representation, Bradford Books Shapiro, L. (2010) Embodied Cognition, Routledge EMOTIONS & ETHICS Semester 2, E&M/M&S Ian Ravenscroft It is clear that emotions play an important role in both ethical judgements and ethical motivation, but the nature of the connection between emotions and ethics is a matter of dispute. We will begin by looking at important research on the evolution of emotions and on cultural variation in emotional expression. Then we will examine a variety of philosophical theories about the role of emotions in ethical life before turning to important new empirical work on emotions and ethics. One issue of particular interest will be the role emotions might have played in the evolution of moral behaviour. (For students taking Dr Eriksson's seminar on the evolution of cooperation there will be useful points of connection here.) We will also consider ways in which emotions may provide strategies for bringing about ethical change, both in ourselves and in our communities. I think an honors seminar should address issues of current interest to the profession, be inspiring, and be fun. My aim is that students will have a good time and learn a heck of a lot. Besides learning about emotions and ethics, I also hope you'll learn about contemporary philosophical method and about writing a good essay. Preliminary reading: We will look particularly at work by Jesse Prinz, Jonathan Haidt and Robert Frank (amongst others). A fun (infuriating?) place to begin is Haidt, J. & Kesebir, S. (2010). "Morality", in S. Fisk & D. Gilbert (Eds.) Handbook of Social Psychology (Hobeken NJ: Wiley) 5th Edition. You can request a copy from Jonathan Haidt's website: http://people.virginia.edu/~jdh6n/moraljudgment.html Feel free to contact me with questions or comments: ian.ravenscroft@flinders.edu.au ETHICS AND LITERATURE Semester 2, M&S Craig Taylor This seminar will examine recent debates concerning the possible role of literature as a mode of moral thought contributing to moral understanding. Is the role of literature in moral thought simply to provide good examples to aid someone’s understand of some (perhaps difficult) moral problem or concept, examples that are superfluous once the relevant moral problem or concept is understood? Or, are the ways in which literature (though not necessarily just literature) illuminates important human values essential to any adequate understanding of those values? Here there is a divide, at least in the case of philosophers broadly in the analytic tradition, between two conceptions of moral thought and reflection; a divide that is illustrated by a now well known exchange between Cora Diamond and Onora O’Neill (who offer respectively affirmative and negative answers to the second question above). The exchange between Diamond and O’Neill then forms part of the preliminary reading for this seminar, and the seminar itself will examine in detail arguments by various contemporary philosophers concerning the possible role of literature as a mode of moral thought and the relation between literature and moral thought and understanding more generally. In particular, we will examine arguments here by, amongst others, Alice Crary, Gregory Currie, Cora Diamond, Peter Lamarque, Iris Murdoch, Martha Nussbaum, Onora O’Neill and D. D. Raphael. Preliminary reading: Diamond, C. 1991. “Anything but Argument?” In her The Realistic Spirit, 291308. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. O’Neill, O. 1980. “Review: The Moral Status of Animals, by Stephen Clark”. The Journal of Philosophy 77(7): 445. Further readings to be provided but if you are keen you could look also at: Lamarque, P. 2009. The Philosophy of Literature. Oxford: Blackwell, chapter 6 and 7. ‘Literature and/as Moral Philosophy’ New Literary History 15 (1983), especially papers by Nussbaum, Diamond and Raphael 7. STUDY ADVICE We hope that you will enjoy and get a great deal out of Philosophy Honours. The crucial determinant of this is your own level of commitment and participation. Seminars are not lectures. To ensure success remember the following: It is essential to keep up with seminar reading. Don’t miss classes unless there are extenuating circumstances. Speak to your supervisor and seminar coordinators about potential problems before they become severe. Cut down on part-time work and distracting social life – it’s only one (very important) year of your life. One of the things being tested is your ability to apply yourself to your studies under your own direction. It can help to treat the Honours year as a 35-hour-a-week job. Make appointments with yourself and stick to them! 8. START OF YEAR MEETING A start of year meeting for Honours students and staff will be held in late February 2012. This will be an opportunity to meet fellow students, and to receive information about seminars and Honours administration. You will receive email notification of the meeting details in February. 9. ASSESSMENT The contribution of individual pieces of assessment towards your overall Honours degree classification will be determined as follows: Adelaide: thesis 40%, each seminar essay 20% Flinders: thesis 50%, each seminar essay 16.66% The following marking scales are used: Adelaide 0-49 Fail 50-59 Class III 60-69 Class IIB 70-79 Class IIA 80-100 Class I Flinders 0-49 Fail 50-64 Class III 65-74 Class IIB 75-84 Class IIA 85-100 Class I For the rules governing the determination of overall degree classifications, see Section 10 below. SUBMISSION FORMAT Each piece of Honours work must be submitted in triplicate, as follows: two printed copies to the Philosophy Office at the university where you are enrolled; one electronic copy emailed to your Honours Coordinator. Each printed copy should have your department’s essay cover sheet on the front. MARKING Each individual piece of work (either seminar essay or thesis) will be marked by two examiners – where possible, one from Adelaide and one from Flinders. Since each piece of work is marked by at least two examiners, requests for remarking will only be granted in extraordinary circumstances. The Department recognises the importance of feedback. All first Semester essays submitted on time are required to be returned to students by midAugust 2012. DEADLINES AND PENALTIES The due dates for seminar essays are as follows: First Semester Essays 12 pm Friday 22 June 2012 Second Semester Essays 12 pm Monday 12 November 2012 The thesis due dates, for both full-time and part-time students, are: Semester 1 Commencement 12 pm Monday 29 October 2012 Semester 2 Commencement 12 pm Monday 11 June 2012 Overdue work will be penalised at a rate of 2% for each working day overdue. Work submitted more than two weeks late without an extension will not be marked. There are penalties for exceeding the seminar essay and thesis word limits. In general, the following penalties (deducted from the percentage mark achieved in the relevant assessment component) apply: Exceeding the word limit by more than 25% Exceeding the word limit by more than 50% Exceeding the word limit by more than 75% 5 marks 10 marks 20 marks If an essay or thesis exceeds the word limit by more than 100%, it will not be marked. EXTENSIONS Honours Coordinators only can authorize extensions. Extensions will only be granted on significant medical or compassionate grounds. Requests for extensions must be made in writing and must be supported by appropriate documentation from a doctor or counsellor. Do not ask your Seminar Coordinator for an extension. Fill out Extension application forms available from the respective Philosophy Departments to be returned to Honours Coordinator. The request for an extension should always be made before the due date. Pressure of other work will not be accepted as grounds for an extension. 10. DEGREE CLASSIFICATION Degree classifications are determined by an examiners’ meeting governed by the following rules. The figures they contain refer to the Adelaide scales. Flinders students who are unsure about the translation into the Flinders equivalents should refer to the Flinders Honours Coordinator. 1. The purpose of the Honours Examiners’ Meeting is to assign degree classifications which appropriately reflect the assessed performance of students who have completed the requirements for Honours in Philosophy. Single Honours Philosophy students complete three assessed seminar courses and one dissertation. The degree classification is based upon the grades awarded for these assessed components, with each seminar contributing 20% and the dissertation contributing 40%. 2. Grades for each assessed component of the Honours Program (i.e., for each seminar and dissertation) will be reported to the Examiners’ Meeting as agreed whole number percentage marks. These marks will be agreed before the Examiners’ Meeting, and not adjusted during the meeting. 3. The weighted average of the grades awarded for the assessed components will be calculated to one decimal place. Using the Adelaide grading scheme: If the weighted average falls in the range 49.5-58.4 inclusive, the candidate will be assigned to the Third Class. If the weighted average falls in the range 59.5-68.4 inclusive, the candidate will be assigned to the Second Class, Division B. If the weighted average falls in the range 69.5-78.4 inclusive, the candidate will be assigned to the Second Class, Division A. If the weighted average lies at or above 79.5, the candidate will be assigned to the First Class. 4. If the weighted average falls in the discretionary bands: 48.5-49.4 inclusive 58.5-59.4 inclusive 68.5-69.4 inclusive 78.5-79.4 inclusive the Examiners’ Meeting will discuss whether to assign the candidate to the immediately higher class. A case for assigning the candidate to the higher class must be based solely on the grades awarded in each of the assessed components. Such a case can be supported by: i) a predominance of component marks in the higher band ii) a dissertation mark of 55 or better (for promotion to the Third Class) a dissertation mark of 65 or better (for promotion to the Second Class, Division B) a dissertation mark of 75 or better (for promotion to the Second Class, Division A) a dissertation mark of 85 or better (for promotion to the First Class) iii) evidence of improved performance over the course of the candidate’s Honours studies. 5. Within the First Class, candidates will be assigned to the Upper, Middle or Lower third of the First Class. In making these assignments, the Examiners’ Meeting will exercise its judgement concerning whether the candidate’s assessed performance ranks in the upper, middle or lower third of those to which First Class degrees have been awarded in Philosophy at Adelaide and Flinders. Data will be provided to the meeting concerning the distribution of weighted averages of previously awarded First Class degrees. The discussion will be guided by these data. In addition: - a case for the award of a Middle First will be supported by a predominance of marks in the band 87-93 inclusive, or a thesis mark of 90 or better - a case for the award of an Upper First will be supported by a predominance of marks of 94 or better, or a thesis mark of 95 or better. 6. The Examiners’ Meeting will not discuss any extenuating personal circumstances which may have affected a student’s performance. Such circumstances are to be taken into account, where appropriate, through the granting of extended deadlines on assessed work, at the discretion of the Honours Coordinator. The marks submitted to Examiners’ Meeting are marks for assessed components which have been agreed after taking into account any such circumstances. HONOURS PHILOSOPHY ADMISSION FORM 2012 Students intending to take up their offer do Philosophy Honours in 2012 at either The University of Adelaide or Flinders University should print, complete and return the following Acceptance Form to the Honours Coordinator in the department in which they intend to enrol. Please in include your preferred seminars. Which seminars go ahead will depend on numbers of students expressing an interest in the topic. Name Student Number Address Phone Numbers Home: Work: Mobile: Email Department Adelaide Flinders Thesis Topic Thesis Supervisor Seminar Courses 1. 2. 3. I satisfy the four conditions for eligibility for admission into the Honours program set out in Section 2 of the 2012 Honours in Philosophy Handbook. signed: ___________________