Susanna Smit – MUHI 331 – Dr. Platt – November 23, 2015 Smit

advertisement

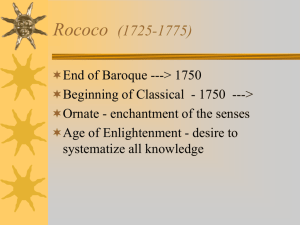

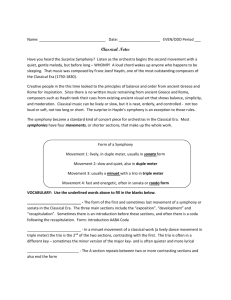

Susanna Smit – MUHI 331 – Dr. Platt – November 23, 2015 The history of the symphony is a vital topic in regards to both the early classical period and the development of major genres. This genre persists to modern day and has undergone countless variations. Its beginnings lie in the early eighteenth-century; during this period the genre underwent the transformation from loose categorization to formal structure. Different decades of the era brought different ideas to the genre, while various schools and locations brought composers together. In conjunction with the development of the symphony comes the development of sonata-allegro form, which starts out as a harmonic form and eventually formulates complex thematic requirements. This form is found throughout the symphonies of this time period, and slowly changes with each work produced. Following a general explanation of the changes the eighteenth-century symphony underwent, four representative composers have been chosen in order to track the progression of the symphony. Paired with each composer is a characteristic work that exemplifies the time, composer, and area. Georg Matthias Monn’s Symphony in Bb Major, Bb2, begins the transition out of baroque and into classical style that took place under the Austrian monarchy; Antonio Brioschi follows a few years later with his Symphony in Bb Major, Op.II/54, which contains innovative harmony and a more fully developed sonata form. Franz Xaver Richter, a member of the Mannheim School, harkens back to the older learned style in his Symphony in C Major while including contemporary devices, and Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf presents a futuristic Symphony in C Major that pushes harmonic boundaries of the era. To examine the symphonic works of representative composers, one must understand the general progression of style and form in the early symphony. The earliest symphonies commonly follow a three-movement progression that alternates fast, slow, and fast for movement tempos (Rudolf 1982, p. 142-143). The first movement of the symphony is either a precursor to Smit 2 or a variant of sonata form, while the second and third movements may be in many different forms. The second movement starts out in simplistic forms, but eventually progresses to become more complex. The third movement of early symphonies is often another sonata form variation, but as time progresses it deviates. In early symphonies there is sometimes elision between the second and third movements, which reveals the opera sinfonia’s influence on the genre (Rudolf 1982, p. 145). This elision phases out, but an increased attention to continuity in the work as a whole takes hold (Will, p. 493). With the addition of a fourth movement, typically in minuet and trio form, comes the addition of instruments. Symphonies in the second half of the century begin to add horns and oboes or flutes, eventually adding a full wind section with occasional percussion. The length of each movement and therefore the overall symphony increases dramatically as time goes on. While structure represents a large part of the changes, thematic and harmonic innovations take place in this period as well. The style of each symphony will vary by composer, but the general trend is to increase harmonic complexity. Each subsequent generation explores more distantly related keys, coupled with unexpected harmonic content and chromaticism. The use of baroque learned style, or counterpoint, gradually diminishes as the genre progresses and gives way to longer melodies. The inevitably linked sonata form must also undergo alterations. Froggatt points to the appearance of a secondary theme as the true mark of a fully formed sonata-allegro movement, and composers gradually move from only changing key to creating stark melodic contrast within their expositions. Hepokoski examines instead the importance of the medial caesura to the overall expositional structure. Some of the following symphonies contain a pause before progressing to the secondary key area of the exposition, but an integral part of Hepokoski’s argument involves the building of tension through various methods. These methods include a structural dominant, repetitive half cadences, or changes in Smit 3 dynamic and texture. The absence of these methods creates a weak break in the exposition, unlike what is found in textbook examples of sonata form (Hepokoski, p. 124-125). The development and recapitulation are open to a freer interpretation, but subtle changes can be seen in these sections as well. The development gains length, and in relation to the harmonic innovation mentioned previously, gains interest. The recapitulation of early symphonies is often sparse, and does not contain a complete restatement of themes. As the form gains traction, the recapitulations become more complete. Georg Matthias Monn is well known today for his contributions to symphonic form in the beginning of the eighteenth-century. The issue that lies with examining his works is one of attribution. His brother often signed his works by only his last name, creating a multitude of works with no clear composer (Rudolf 1985, p. lxxi). Georg Matthias Monn has a few salient features that allow his works to be discerned. His orchestration is decidedly smaller than that of his brother; Matthias Monn prefers three or four string parts with occasional wind additions. He is seemingly random in his choice of winds, but their presence is relatively rare. In terms of form, Matthias favors a three-movement symphony following the fast, slow, fast progression; only a few of his works contain an interjected minuet movement. Most of Matthias Monn’s movements follow binary form and variants thereof. Simple binary may be found in slow movements and final movements while expanded versions such as rounded binary and sonata form appear in first movements and occasional finales. Matthias Monn’s sonata form does not have a full recapitulation, but still follows the general structure (Rudolf 1982, pp. 92-99). Matthias Monn’s symphonies are representative of Viennese symphonies in his time. He follows the practice of his contemporaries with three-movement symphonies that are scored for two violins, viola and bass. Monn also commonly links the second and third movements of his works Smit 4 with half cadences, as is seen later in Brioschi’s work (Rudolf 1982, pp.140-145). In terms of sonata form, Monn follows the general tonal structure expected, but does not always follows the three-part thematic form. As is typical of early sonata form, the first half contains a primary theme, a possible secondary theme that may not be contrasting, but is in the secondary key. The second half may contain a small amount of development, and a return to all or part of the themes (Rudolf 1982, pp. 145-146). Each of these elements points to the developing sonata form as a part of the overall symphonic genre. The Symphony in Bb Major, Thematic Index Bb2, is one of the most well documented works by Matthias Monn. As would be expected, the symphony is in three movements with an Allegro, Andante Molto, and Presto. The outer movements are close to sonata form, while the inner movement is in binary form, features also indicative of Matthias Monn’s early symphonies (Rudolf 1985, p. lxxx). The first movement of an early symphony is the most complicated and often the longest as well. Reflecting the development of classical style, the Allegro follows the forming sonata-allegro structure but begins with a canon at the unison, which is followed by a canonic sequence. The movement follows the expected form, with a slightly contrasting secondary theme in the dominant key (Rudolf 1985, p. lxxx). The secondary theme of this movement is marked by a medial caesura. In accordance with structural norms, the material following the medial caesura is at a piano dynamic. However, there is not a large amount of rhythmic or harmonic build into the medial caesura, making it weak (Hepokoski, p. 117). The exposition ends with another canonic passage (Rudolf 1985, p. lxxx). Monn’s use of canon reveals his ties to baroque style. Counterpoint was still common in symphonic repertoire, as the learned style dominated baroque works of recent years. The use of counterpoint continues into later symphonies, most notably by Richter, who found inspiration from early symphonic Smit 5 repertoire (Van Boer, p. xvii). The exposition is actually divided into three larger sections when examining cadential structure. It has three significant authentic cadences instead of the usual two that would end the primary and secondary themes. The secondary theme elides into the development of the Allegro without a double bar or repeat sign to signify the end of the exposition (Rudolf 1982, p. 161). The development expands on the opening canon by transposing it and expanding it to include complicated imitation. Finally, the primary theme, secondary theme, and canonic passage reappear in the recapitulation (Rudolf 1985, p. lxxxlxxxi). The Andante Molto is in simple binary form in Eb major. The theme is an ornamented melodic line found in the violins. As is typical in Monn’s slow movements, the melody is placed in the higher voices for clarity, while the lower voices play a simplified melody or supporting harmony underneath. The movement follows a three-part harmonic plan like that of the first movement, wherein the secondary key is the dominant. The first half of the Andante Molto drives toward a half cadence on Bb, while the second half brings the movement back to Eb major through a series of sequential changes. Another feature exemplified in this movement that is commonly found in Monn’s slow movements is his use of parallel material between the two sections. In this case, each begins with the same ornamented melody, in different keys, before moving on to contrasting material (Rudolf 1982, pp. 210-211). Unlike his other slow movements, the second movement of Bb2 allows for differentiation between themes in the first half as shown in Example 1; the second theme can be seen in measure 5, with changes taking place in the bass part as well. (Rudolf 1982, p. 212). Smit 6 Vln. Cb. Example 1: Georg Matthias Monn, Symphony in Bb Major, Bb2, Andante Molto, mm. 1-10 (Rudolf 1982, p. 213) The Presto of this symphony is the longest finale movement in all of Monn’s symphonies at 137 measures. It is in 2/4, which implies a more serious nature than that of his other finales, which are often in a dance meter. All of Monn’s finales are marked by a strong central cadence in the dominant (Rudolf 1982, p. 236-237). This movement is one of six finales to employ sonata form; the distinction from full sonata form lies in the number of themes. Presto contains two themes in each key area and two independent transitional themes, which creates an exposition that is comprised nearly completely of thematic material (Rudolf 1982, pp. 240-242). Froggatt’s examination of secondary themes would place this movement into the realm of a very divergent sonata form, but it may be considered a precursor to sonata form instead, as it does not follow the traditional structure (p. 231). Instead of distinct thematic material, Monn opts for a multitude of ideas, which is unusual considering the repetitive tendency of early eighteenth- Smit 7 century composers. The development is relatively unique as it moves through each theme sequentially, an unusual practice for Monn. The recapitulation is preceded by a strong cadence and a break in all parts. The recapitulation of this movement is typical in structure; it begins with the primary theme in tonic and moves through the other themes (Rudolf 1982, pp. 240-242). The Milanese School of composers played a significant role in the conception and development of the Classical symphony. Giovanni Batista Sammartini and Antonio Brioschi are considered the most influential composers of this group, in part due to their amount of surviving works. Many of their early symphonies are trio symphonies, as the years progress symphonies for four string parts become more prominent. While both types of symphonies are a mixture of Classical and baroque styles, the trio symphonies show a preference for baroque while the fourpart symphonies lean toward Classical style. These symphonies employ homophonic texture, major keys, and repetition. Additionally, they follow the fast, slow, fast progression that was typical of three movement works. They begin with a longer first movement, which leads to a slow, minor second movement. The finales tend to be in a dance form (Churgin 2012, p. 105). Brioschi’s later symphonies follow a similar general format. The first movement is the most involved and uses an early sonata form. Typically, they include a long development and thematic freedom. This freedom may allow for a nearly monothematic form in some cases, but in all cases places an emphasis on the P theme. The slow movements are nearly always in minor, tonic or relative, and explore lyricism (Churgin 1985, p. xiv). The use of tonic minor is more common, as this contrasts with baroque practice. Brioschi’s finales avoid the minuet form used by Sammartini and instead opt for 3/8 dance forms (Churgin 2012, p. 106). Antonio Brioschi’s Symphony in Bb Major, Op.II/54 is a representative example of his symphonies written in four parts. It was given many titles in its time, such as sinfonia or Smit 8 concerto, as the term symphony had not yet taken hold (Mandel-Yehuda 2012, p.139). MandelYehuda explains that all of Brioschi’s outer movements are in two parts, and most of these are in a loose sonata form. The first part of each movement is expositional; they present the theme and undergo harmonic movement to the dominant key, ending with an authentic cadence. Brioschi themes do not follow the conventional contrasting model of later sonata form. Instead, his themes are often melodically related, and contrast can only be found in harmonic structure. Because of this, the S theme is not considered fully formed, which is indicative of the underdeveloped sonata form present (Mandel-Yehuda 1999, 3.2.1-3.2.2). The monothematic tendency mentioned by Churgin is contested by Mandel-Yehuda who suggests a lack of contrast instead. During the development of sonata form, the appearance of a secondary theme is vital. Brioschi is in the transitional between composers who utilize a secondary key, and those who have a fully formed secondary theme. The key in his sonata forms always changes, creating a three part harmonic form, however the secondary subject is often related to the first, but does not simply repeat the primary theme in a new key. These distinctions make it difficult to place him definitively on one side or the other (Froggatt, p. 231). Regardless of the technical classification, Brioschi’s first movement, Allegro Assai, places an emphasis on the primary theme by allowing it to take up nearly three quarters of the exposition, diminishing the weight of the secondary theme. However, the secondary theme is preceded by a short caesura, which makes the transition slightly more obvious (Mandel-Yehuda 2012, p. 141). This caesura is not preceded by any of the building principles explained by Hepokoski, therefore making it a relatively understated stopping point (p. 124-125). The development of this movement exposes Brioschi’s contrapuntal nature. In general, he uses more counterpoint than Sammartini, and the return of this style in late eighteenth-century symphonies may be linked to Brioschi. The development of Smit 9 Op.11/54/I begins with independent string parts that gradually build into a fuller texture through imitation as seen in example (Mandel-Yehuda 1999, 3.3.5) Example 2: Antonio Brioschi Symphony in Bb Major Op. II/54/I mm. 23-24 (Mandel-Yehuda 1999, 3.3.5) Following the free part writing he employs multiple other forms of learned style. He involves all parts in an imitative section, oscillates between solo and tutti, and delves into ornamented fourthspecies suspension. The retransition of Allegro Assai features reduced rhythmic activity and thinning texture that is common for Brioschi. His retransitions often contain some sort of contrasting element to bring interest to the section. Only half of Brioschi’s sonata form first movements contain dominant pedal point preceding the recapitulation, and Op.II/54 is one of these. The basso continuo provides a steady repetition of the dominant, F (Mandel-Yehuda 1999, 3.3.6). Brioschi’s recapitulations are often free in nature; beginning with an exact recapitulation, and then spiraling into other material (Mandel-Yehuda 1999, 3.4.2). In this symphony he begins with an exact repetition of the P theme, which is suddenly interrupted by an Ab in the first violins. This disruption leads to a short period of harmonic instability that eventually leads to the return to Bb Major and the conclusion of the movement. Mandel- Smit 10 Yehuda explains that the recapitulation is almost a second development (3.4.4). His recapitulation is a simplified version of the development of this movement, with the largest difference found in harmonic stability. While the development is unstable, the recapitulation offers stability in the subdominant, which reinforces the tonic and leads to the concluding authentic cadence (Mandel-Yehuda 2012, p. 143). In contrast to his typical non-modulating, long second movements, Brioschi’s Largo Staccato of Op.II/54 is relatively short, and has a brief tonicization of D Major (Churgin 2012, p. 106). This movement is in the more baroque relative minor and uses unexpected harmonic content. Brioschi uses diminished seventh chords to add interest, a feature that was highly innovative for the early symphony; this chord can be seen on the downbeat of measure 5 of Example 3. vln. 1 vln. 2 vla. cb. Example 3: Antonio Brioschi, Symphony in Bb Major, Op. II/54/II, mm. 1-5, (Mandel-Yehuda 2012, p. 140) Additionally, he varies the texture throughout, occasionally reducing the orchestration to one voice (Churgin 1985, xiv-xv). The movement contains several telling Brioschi trademarks besides the seventh chord; he uses staccato chords, snap rhythms and suspensions throughout. Smit 11 While most sources present the slow movement ending on a half cadence, a few scores substitute an authentic cadence. The open-endedness of a half cadence is highly unusual for the time and can only be found in three of Brioschi’s inner movements (Mandel-Yehuda 2012, p. 139). Sources do not concur on whether or not the second and third movements of this work are continuous, but this may be the case (Churgin 1985, pp. xiv-xv). If they were in fact meant to elide, it would liken this symphony to those of Georg Matthias Monn of the previous generation. The last movement of this symphony returns to Bb Major. It is in sonata form like the first movement, but its second theme is slightly more pronounced. The primary theme is presented in imitation between the first and second violins, while the secondary theme contains syncopation and ornamentation. This suggests a more fully realized sonata form, and also gives an example of Brioschi’s tendency to input a rest in all parts before the secondary theme (Mendel-Yehuda 1999, 3.2.4). Later sonata form expositions follow this trend, which requires a cadence and a break, called a medial caesura, before the secondary theme. Froggatt’s distinction between the presence and lack of a secondary theme is dependent on contrast, and by this method Brioschi’s Presto achieves a secondary theme (231). However, the development of this movement is rather short, and focuses on the primary theme. Additionally, it ends with an incomplete recapitulation that was common for Brioschi. He often condensed his themes for a shorter recapitulation with more variation (Mandel-Yehuda 1999, 3.4.5). Therefore it can be deduced that Brioschi’s Allegro Assai is a full sonata form movement with a weak secondary theme, while Presto is a full sonata form movement with a contrasting secondary theme, but insufficient second half. His Symphony in Bb Major, Op.II/54 is a mixture between baroque and Classical styles that represents the transition into a formal symphonic form. Smit 12 Franz Xaver Richter was a Bohemian composer of the eighteenth-century (Van Boer p. xv). He began his professional career in Vienna, where his works reflected the contrapuntal theory found in Johann Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum and early composers like Matthias Monn. He retained a fondness for counterpoint throughout his career, and uses both the imitative and non-imitative forms (Murray, p. 304). Other features of his early symphonies are indicative of most symphonies produced during the early eighteenth-century. They are scored for string orchestra: two violins, one viola, and basso continuo. The basso continuo part often features figured bass. His early symphonies’ first movement form is based on repetition. His main themes are often triadic and may contain dotted rhythms. He brings these themes through a series of keys, with little to no development (Van Boer, pp. xxii-xix). Critics like Burney did not consider this practice to be innovative, instead he remarked, “Indeed, this species of iteration indicates a want of invention in a composer, as much as stammering and hesitation imply want of wit or memory in a story-teller” (Murray, p. 305). The lack of a solid primary theme in conjunction with minimal development leads to the assumption that Richter’s early symphonies did not follow sonata form in any of their movements, instead he followed a binary form with small deviations that may have led to sonata form. In spite of his adherence to older styles, he maintained popularity. In 1747 Richter was invited to join the Mannheim Kappelle. The Mannheim Kappelle was created to bring recognition to its patron, Carl Theodor; it brought talented musicians together, creating a highly skilled orchestra. Within the orchestra were numerous composers; referred to as the Mannheim School. The early Mannheim School included Johann Stamitz, Ignaz Holzbauer, and Franz Richter. These composers represent the most influential of the first generation in Mannheim. Although these composers are grouped by their occupation, they did Smit 13 not have similar compositional styles. Richter joined the Mannheim School as an established composer (Murray, p.303). Upon his employment, Richter’s compositional style underwent subtle changes. He began scoring his symphonies for the orchestra available to him, which opened the possibility for the addition of two horns and two flutes or oboes. Additionally, the basso continuo parts were no longer figured, and the strings enjoyed fuller harmonies (Van Boer, p. xvii). Unlike many symphonies in Vienna and Mannheim in this period, Richter preferred a three-movement work like his predecessors, however he did write a few four-movement pieces as well. By this period of his life, the first movement of his works had begun to resemble sonata form. He often employs a double statement of the primary theme and a lyrical second theme. Additionally, the transition and closing are more developed than in earlier years. Keeping with his compositional style, each section is interspersed with contrapuntal passages. Building on his previous exploration of keys, his developments often include unexpected modulations. His themes do not vary much in his development, which is also similar to his early symphonies (Van Boer, p. xix). Richter often uses contrapuntal methods to repeat his theme such as sequence, imitation, and chain suspensions. Occasionally, his use of counterpoint distracts from the formal structure of his movements, so it can be said that his focus was not on sonata form, but instead on melodic content (Murray, p. 305). The second movements of Richter’s late symphonies are usually in binary form. He uses both simple and rounded binary, and includes lyrical melodies. He often changes the texture of his second movement by including only melody and bass, harkening back to much earlier works. As is typical with Richter, there is a use of counterpoint throughout, but the emphasis of the movement is placed on the musicality of a rhythmically complex theme (Van Boer, p. xix). While Richter preferred a three-movement symphony, in rare cases he includes a fourth movement. When the fourth movement is present, the third is usually Smit 14 a minuet. The finale of his symphonies can follow the form of an Italian Presto, a minuet like the third movement, or a fugue. Symphony in C major, Thematic Index 11, is an example of a rare Richter fourmovement symphony. It is scored for two oboes, two horns, and string orchestra. This piece was written during Franz Richter’s time in Mannheim, and therefore was most likely written for the Mannheim Kappelle. It may be in four movements as a way of giving in to the more modern practices of Richter’s peers in the Mannheim School. It begins with a mostly developed sonata form movement. The triadic theme is stated first in the horns and strings (Van Boer, p.xxiii). It is an example of the Mannheim rocket, defined as a rising triadic theme in equal note values (Wolf). Ever resourceful in his use of keys, the development of this movement undergoes many modulations, and includes some chromaticism in the strings (Van Boer, p. xxiii). The winds enjoy relatively independent parts in this movement, largely due to Richter’s use of counterpoint. The movement does not have a distinguishable secondary theme, making it more analogous to the monothematic expositions found in Haydn pieces. Monothematic sections are commonly paired with the use of counterpoint, which is the case with Richter’s work (Froggatt, pp. 230231). The second movement is in C minor, which follows Richter’s typical key assignment. Additionally, the theme contains ornamentation, short rhythms, and a small amount of syncopation, creating the rhythmic complexity expected in Richter’s second movements (Murray, p. 305). The winds scoring of this movement is rather light; they serve only to flesh out harmonies and add texture variation (Van Boer, p. xxiii). The third movement is a minuet, as can be expected from Richter’s compositional trend. However, this minuet is slightly irregular. Richter disrupts the meter by breaking the melody into multiple parts. The harmonic structure of the movement is static, placing emphasis on the development of the theme. While the movement Smit 15 begins with full involvement of the winds, the trio section brings the oboes to the forefront. The soloistic line of the oboes carries the minor mode trio through to the end with sparse string accompaniment. Richter also brings suspensions to the contrapuntal oboe duet (Van Boer, p. xxiii-xxiv). The last movement of this symphony is a Presto, which uses dynamic contrast to highlight the use of counterpoint (Van Boer, p. xxiv). While it follows sonata form, as was typical of Richter, the movement is not as short as expected (Murray, p. 306). Franz Richter’s adherence to antiquated symphonic style makes his works into a link between conservative and innovating composing. Although he seems out of sync with his contemporaries, he also brought subtle innovations to the symphonic repertoire (Murray, p. 306). Richter’s use of sonata form in the first and last movements of his symphony relates to the practice of his predecessors. His use of counterpoint also ties his works to early classical style and baroque influence. Richter’s Symphony in C Major holds on to older styles while acquiescing to modern practices. Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf contributed at least 107 works to early symphonic repertoire in the late eighteenth-century. His pieces undergo significant changes as the genre progresses. Dittersdorf is considered part of the Viennese School, which included Joseph Haydn and W. A. Mozart (Will, p. 483). Before 1766 Dittersdorf kept his symphonies to three movements, following the fast, slow, fast outline. His symphonies employed gallant style, which was popular with audiences of his time. He commonly uses Trommelbass, which builds intensity through the use of syncopation, fanfare, and tremolo sixteenth notes. His ideas often blur into one another, with the main themes being formed from repeated small sections. His early first movements are short, with thinner textures that relate to those of previous generations. They can be found in binary form and a simplistic version of sonata form. The following slow movement is typically longer and full of expressive harmony; they are always in a minor key and keep a somber mood Smit 16 through modulations. In contrast, his third and final movements were often light hearted and witty. He brings about ideas of grandeur in his themes, but added syncopation and unexpected harmonies set a more amusing tone (Will, pp. 485-486). After 1770, Dittersdorf’s symphonies become larger in multiple facets. Most notably, his symphonies are now in four movements, often fast, slow, minuet, fast, but with some variation. He begins to write longer symphonies through the use of repetition and a multitude of themes. Instead of the repetitive small sections found in his earlier melodies, he begins to use longer melodic phrases with more complex harmonies underneath. He also experiments with the use of gallant style that interrupts or expands upon formal structure. Dittersdorf keeps his developments proportionally short, and his recapitulations are more indicative of modern sonata form. The second movements of this period do not use Trommelbass, and instead have a more active bass part. The third and fourth movements in his middle period are longer and show more complexity, but are in the forms of minuet and rondo. Dittersdorf also begins to use an expanded orchestra in this period, adding two oboes, and two horns. It may also be noted that he begins to place an emphasis on the continuity of the work and how each movement is related to the next (Will, p. 487). Following his middle period, Dittersdorf takes a slight detour and focuses his energies on Characteristic Symphonies that are based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Dittersdorf completed twelve symphonies to represent the story, and each follows a four-movement form. These symphonies further his growth in sonata form and harmonic interest, but place most of their focus on the importance of programmatic elements (Will, pp. 487-493). His last period mimics many of the changes found in the Metamorphoses symphonies. They are longer and have four movements, but also allow for freedom within their structure. In some cases Dittersdorf splits completely Smit 17 from traditional sonata form. Additionally, these symphonies contain more chromaticism, and keys related by thirds (Will, p. 494). One of the first works from Dittersdorf’s last period is the Symphony in C major, Thematic Index C14. This symphony is in four movements, which had become the standard by the late eighteenth century. This symphony uses a much larger orchestra than what has been seen previously. Dittersdorf writes for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, strings, and timpani. Larger orchestras were becoming increasingly common in this time, and technological advancements allowed for expanded instrumentation. The first movement is in sonata form, but begins with a slow introduction. These were common, and were used extensively by Dittersdorf’s contemporaries. This particular introduction is marked maestoso and continues for thirty-three measures. The introduction is not particularly noteworthy, as it lacks a strong melody (Badura-Skoda, p.xxxiv). It was relatively common for Dittersdorf to begin his symphonies with a section that had little structural or thematic weight (Will, p. 495). The exposition begins with a lyrical theme that is contrasted by a tutti section. The use of winds is restricted mostly to the tutti sections; the use of winds is mostly for contrast and textural change. Unlike Richter, whose counterpoint allowed for independent wind lines. The secondary theme of this movement is in the dominant as expected, but is relatively short lived and gives way to a tertiary theme in Eb Major, referred to as an epilogue theme. The presence of a definite secondary theme makes this sonata form movement’s structure apparent. There is a fully formed second key along with a heavily contrasted secondary theme, regardless of its short length, pointing to the growth of the form (Froggatt, p. 231). The exposition ends in G major, and the following development is in E major (Badura-Skoda, p. xxxiv). Through these key progressions it is obvious that Dittersdorf is expanding his modulatory techniques to include third related keys Smit 18 and mediant progression. This advanced use of keys highlights the innovations taking place in the late eighteenth century symphony and builds upon the key usage of Richter. The development continues with the epilogue theme in the new key of E major. As is common throughout Dittersdorf’s career, the development section is short, only twenty-five measures in this particular piece. The recapitulation follows as expected, with the primary theme in the tonic key. However, it shifts the transitional theme into D minor and omits the tertiary theme. Surprisingly the primary theme is stated in another mediant key, A major. After transitioning back into the tonic key, the coda reprises the missing tertiary theme (Badura-Skoda, p. xxxiv). The repositioning of thematic material in the recapitulation is found in sonata forms of the next century and shows flexibility within sonata form that has not been seen before. While there is leniency within the structure, the presence of sonata form is unmistakable. The following Andantino is in F major. Unlike the first movement of this symphony and many of the other second movements of this period, the Andantino is presented with minimal harmonic change (Will, p. 496). It is in rondo form, and has an expressive melody that BaduraSkoda describes as “nearly a Lied” (p. xxxv). In this movement Dittersdorf thins the texture by removing the clarinets and timpani, and reserving the winds until the second section of the rondo. In concurrence with the four-movement progression, the third movement is a minuet. Dittersdorf employs the winds for textural variation in this minuet, with gradual building and thinning throughout. Notably, he uses the trumpets and timpani to create a booming ostinato that allows for chromaticism and harmonic change (Badura-Skora, p. xxxv) As is remarked by Will, Dittersdorf’s minuets often contain sudden modulation, which is in this case connected through a repetitive element, the ostinato (p. 496). Dittersdorf’s final movements favor a rondo or sectional form, and the Finale is no different (Will, p. 496). The Finale is in a variation rondo Smit 19 form, which allows Dittersdorf to break away from the restrictive form of a rondo. Haydn, who influenced many of Dittersdorf’s works, also commonly uses this form. The theme of this movement is also faintly Haydn inspired and opens regally in C major. Unlike what would be expected of a simple rondo, the first section of this movement does not leave the tonic key, it only progresses through a short tonicization of the dominant chord. Dittersdorf treats his ritornellos as developmental sections and brings back his scherzante themes in varied forms throughout the movement. The winds are used for textural effect and dynamic contrast (BaduraSkora, p. xxxv). The expanded use of winds in Dittersdorf’s symphony is a precursor to the extensive role they would eventually play in later symphonies. Additionally, his use of varied forms and a singular sonata form movement foretell later symphonic trends. While each composer presents their own stylistic characteristics, each symphony of the time period examined has ties to the others. The symphonic genre developed substantially in this time period, and with it the sonata-allegro form. The sonata-allegro form converts from a harmonic structure with expanded binary thematic material into a fully realized three-part form. The presence of a secondary theme is vital to the progression of the form, and can be marked by the quality of the preceding medial caesura. Each symphony examined uses a different combination of movement length, number, and form to create a unique step in the path to a unified genre. Small ideas are carried through the century, such as the use of elision, modulation, and counterpoint. The general trend for the century can be summed up as a gradual growth; this is found in orchestration, movement length, and harmonic exploration. Georg Matthias Monn begins the journey with a symphony that straddles the baroque and classical styles; it remains representative of its time through the use of typical orchestration and length while employing contrapuntal techniques throughout. In Milan, Antonio Brioschi focuses on Smit 20 furthering the sonata form of his symphonies, while in Mannheim Franz Xaver Richter balances between a fondness for old styles and a push for innovation. Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf leaves convention behind and surpasses the typical sonata form while continuing the exploration of distantly related keys. The chronology of the symphony in the eighteenth-century can be seen clearly though the similarities and differences of these composers, with each adding innovation to the genre that now permeates musical repertoire. Wordcount: 5943 Smit 21 Bibliography Badura-Skoda, Eva., “Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf,” in The Symphony 1720-1840 Series B Volume I, edited by Barry S. Brook, xiv-xv. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1985. Churgin, Bathia., “Antonio Brioschi,” in The Symphony 1720-1840 Series A Volume III, edited by Barry S. Brook, xiv-xv. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1985. Churgin, Bathia, “The Symphony in Italy,” in The Symphonic Repertoire Volume I: The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, edited by A. Peter Brown, 103-107. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012. Froggatt, Arthur T., “The Second Subject in Sonata Form.” The Musical Times 68/1009 (1927): 230-232. Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. “The Medial Caesura and Its Role in the Eighteenth-Century Sonata Exposition.” Music Theory Spectrum 19/2 (1997): 115-154. Mandel-Yehuda, Sarah, “Antonio Brioschi,” in The Symphonic Repertoire Volume I: The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, edited by A. Peter Brown, 139-143. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012. Mandel-Yehuda, Sarah. “The Symphonies of Antonio Brioschi: Aspects of Sonata Form,” Min-ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online 1 (Summer, 1999) Accessed October 9, 2015. http://www.biu.ac.il/hu/mu/ims/Min-ad/vol_1/brioschi.htm. Murray, Sterling E., “The Symphony in South Germany,” in The Symphonic Repertoire Volume I: The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, edited by A. Peter Brown, 303-306. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012. Rudolf, Kenneth Emanuel., “Georg Matthias Monn,” in The Symphony 1720-1840 Series Smit 22 B Volume I, edited by Barry S. Brook, lxxx-lxxxi. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1985. Rudolf, Kenneth Emanuel. “The Symphonies of Georg Mathias Monn (1717-1750).” PhD diss., University of Washington, 1982. Van Boer Jr., Bertil H., “Franz Xaver Richter,” in The Symphony 1720-1840 Series C Volume XIV, edited by Barry S. Brook, xv-xxiv. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1985. Will, Richard., “Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf,” in The Symphonic Repertoire Volume I: The Eighteenth-Century Symphony, edited by A. Peter Brown, 483-496. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012. Wolf, Eugene K., “Mannheim Style,” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed November 20, 2015. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/17661.