p1a: parameters are properties of universal principles

advertisement

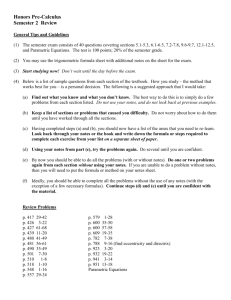

WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 1 FREDERICK J. NEWMEYER UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, AND SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2 WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 3 Crosslinguistic variation — a bit of an embarrassment. If there is a universal grammar, then why aren’t all languages exactly the same? If grammars are shaped functionally, then why is there so much morphosyntactic variation? WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 4 Earliest work — not much focus on variation. The goal — show the sameness of all languages at an underlying level and formulate universal principles. Surface variation attributed to language-particular rules or filters. WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 5 ‘Modern work has indeed shown a great diversity in the surface structure of languages. ... Insofar as attention is restricted to surface structures, the most that can be expected is the discovery of statistical tendencies, such as those presented by Greenberg (1963).’ (Chomsky 1965: 118) • The last sentence of the quote was considered notorious by some. NOAM CHOMSKY IN THE 1960s WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 6 Klima (1964): Dialects differ according to how their rules are ordered. EDWARD KLIMA, 1931-2008 WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 7 Bach (1965): Markedness conventions apply to languages that are ‘typologically consistent’ and ‘typologically inconsistent’. EMMON BACH, 1929-2014 WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 8 Since the late 1970s crosslinguistic variation has been handled in terms of parameters. Parameters have been central to mainstream generative grammar for several decades (the P & P approach). Parametric (and other) variation is ideal for illustrating how many theoretical options there are for handling a particular phenomenon. There have been several architecturally different approaches to variation, each entailing a different division of labour. WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 9 ‘Even if conditions are language- or rule-particular, there are limits to the possible diversity of grammar. Thus, such conditions can be regarded as parameters that have to be fixed (for the language, or for the particular rules, in the worst case), in language learning … It has often been supposed that conditions on applications of rules must be quite general, even universal, to be significant, but that need not be the case if establishing a ‘parametric’ condition permits us to reduce substantially the class of possible rules.’ (Chomsky 1976: 315) • Why then? Kim (1976) showed that Korean obeys a form of the Tensed-S-Condition, even though Korean does not distinguish formally between tensed and non-tensed clauses. WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 10 An inspiration for parameters — the work of Jacques Monod and François Jacob (Monod 1972 and Jacob 1977). JACQUES MONOD, 1910-1976 FRANÇOIS JACOB, 1920-2013 WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 11 Slight differences in timing and arrangement of regulatory mechanisms that activate genes could result in enormous differences: ‘Jacob’s model in turn provided part of the inspiration for the Principles and Parameters (P&P) approach to language …’ (Berwick and Chomsky 2011: 28) WHERE, IF ANYWHERE, ARE PARAMETERS? 12 MY GOALS IN THIS TALK: To outline the approaches to parameters since the late 1970s. To discuss their strengths and their weaknesses. To conclude that a non-parametric approach is best. APPROACHES TO PARAMETERS 13 P1: Macroparametric approaches P1a: Parameters are properties of universal principles P1b: Parameters are properties of entire grammars P2: Microparametric approaches P2a: Parameters are restricted to the idiosyncratic properties of lexical items P2b: Parameters are restricted to the inflectional system P2c: Parameters are associated with functional heads P3: Parameters are stated at the interfaces P3a: Parameters are stated at the PF interface P3b: Parameters are stated at the C-I interface P4: Parameters are not part of UG. Much of variation is a ‘third factor’ effect P4a: Grounded approaches P4b: Reductionist approaches P4c: Epigenetic approaches P5: Parameters are not part of UG. Languages differ from each other in terms of the rules that they possess. Possible rules are constrained by both UG and ‘third factor’ considerations P1: MACROPARAMETRIC APPROACHES 14 I’ll call any approach that partitions languages into broad typological classes ‘macroparametric’. P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 15 This is the core idea of the P & P approach. Both the principles of UG and the possible parameter settings are part of our genetic endowment: ‘[W]hat we ‘know innately’ are the principles of the various subsystems of S0 [= the initial state of the language faculty — FJN] and the manner of their interaction, and the parameters associated with these principles. What we learn are the values of these parameters and the elements of the periphery …. The language that we then know is a system of principles with parameters fixed, along with a periphery of marked exceptions.’ (Chomsky 1986: 150-151) P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 16 The original idea was that there are a small number of parameters and small number of settings. This allowed two birds to be killed with one stone. Parametric theory could explain the rapidity of acquisition, given the poor input, and explain the crosslinguistic distribution of grammatical elements. P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 17 All of the subsystems of principles have been assumed to be parameterized. Many examples from work in GB: P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 18 BINDING (Lasnik 1991). Principle C is parameterized to allow for sentences of the form Johni thinks that Johni is smart in languages like Thai and Vietnamese. HOWARD LASNIK P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 19 GOVERNMENT (Manzini and Wexler 1987). The notion ‘Governing Category’ is defined differently in different languages. MARIA-RITA MANZINI KENNETH WEXLER P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 20 BOUNDING (Rizzi 1982). In English, NP and S are bounding nodes for Subjacency, in Italian NP and S’. LUIGI RIZZI P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 21 X-BAR (Stowell 1981). In English, heads precede their complements; in Japanese heads follow their complements. TIM STOWELL P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 22 CASE and THETATHEORY (Travis 1989). Some languages assign Case and/or Theta-roles to the left, some to the right. LISA TRAVIS P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 23 Fewer and fewer parameterized principles have been proposed in recent years. Why? Because there are fewer and fewer principles! The thrust of the MP — to reduce the narrow syntactic component and to reinterpret broad universal principles as economy effects of efficient computation. P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 24 And economy principles are generally assumed not to be parameterized. The ‘Strong Uniformity Thesis’ (Boeckx 2011): Principles of narrow syntax are not subject to parameterization; nor are they affected by lexical parameters. CEDRIC BOECKX P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 25 Chomsky has explicitly disparaged the search for universal principles: ‘[T]ake the LCA (Linear Correspondence Axiom) [Kayne 1994]. If that theory is true, then the phrase structure is just more complicated. Suppose you find out that government is really an operative property. Then the theory is more complicated. If ECP really works, well, too bad; language is more like the spine [i.e., poorly designed — FJN] than like a snowflake [i.e., optimally designed]’ (Chomsky 2002: 136). P1A: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES 26 So if no UG principles and hence no parameters associated with them, then where to handle variation and the parameters that capture it? Two diametrically opposed hypotheses: 1. Parameters are properties of entire grammars. 2. The sorts of elements that can be parameterized are very restricted. P1B: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF ENTIRE GRAMMARS 27 There has always been the sense that there is something right about the idea that parameters are broad and global, rather than tied to particular functional categories. Parameters from the beginning have been proposed that are not tied to specific UG principles. Rather they seem to be a fact about the language as a whole. P1B: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF ENTIRE GRAMMARS 28 Whether or not V moves to I in a particular language (Emonds 1978; Pollock 1989) JOSEPH EMONDS P1B: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF ENTIRE GRAMMARS 29 Whether V moves to C (to derive V2 order) (den Besten 1977/1983) HANS DEN BESTEN, 1949-2010 P1B: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF ENTIRE GRAMMARS 30 Whether N incorporates into V (Baker 1988) MARK BAKER P1B: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF ENTIRE GRAMMARS 31 If you hypothesize that parameters are ‘macro’ in scope and at the same time diminish the number of UG principles, then it follows that parameters have to be properties of entire languages. The Parameter Hierarchy of Mark Baker’s Atoms of Language is the best known example of treating parameters as properties of entire languages. (Baker 2001) 32 P1B: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF ENTIRE GRAMMARS 33 Some other recent macroparameters: Snyder (2001) Compounding parameter. The grammar [disallows*, allows] formation of endocentric compounds during the syntactic derivation. [*unmarked value] WILLIAM SNYDER P1B: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF ENTIRE GRAMMARS 34 Boskovic and Gajewski (2011) NP/DP macroparameter. NP languages lack articles, permit left-branch extraction, scrambling, and NEG-raising; DP languages do not. ŽELJKO BOŠKOVIĆ JON GAJEWSKI P1B: PARAMETERS ARE PROPERTIES OF ENTIRE GRAMMARS 35 Huang (2007) points to many features that distinguish Chinese-type languages from English-type languages, including: a generalized classifier system no plural morphology extensive use of light verbs no agreement, tense, or case morphology no wh-movement radical pro-drop etc. JAMES HUANG P2: MICROPARAMETRIC APPROACHES 36 P2a: Parameters are restricted to the idiosyncratic properties of lexical items P2b: Parameters are restricted to the inflectional system P2c: Parameters are associated with functional heads What they have in common is that parametric variation is quite localized. This idea is often referred to now as the ‘Borer-Chomsky Conjecture’. P2: MICROPARAMETRIC APPROACHES 37 Hagit Borer, in Parametric Syntax (Borer 1984), made two proposals, which she may or may not have regarded as variants of each other (P2a and P2b): HAGIT BORER P2A: PARAMETERS ARE RESTRICTED TO THE IDIOSYNCRATIC PROPERTIES OF LEXICAL 38 ITEMS ‘Interlanguage variation would be restricted to the idiosyncratic properties of lexical items..’ (Borer 1984: 2-3) Borer gave an example of a rule that inserts a preposition in Lebanese Arabic, that does not exist in Hebrew: f ------> 1a / [PP … NP] P2A: PARAMETERS ARE RESTRICTED TO THE IDIOSYNCRATIC PROPERTIES OF LEXICAL 39 ITEMS Manzini and Wexler (1987) pointed to language-particular anaphors that have to be associated with parameters: cakicasin and caki in Korean; sig and hann in Icelandic. MARIA RITA MANZINI KENNETH WEXLER P2A: PARAMETERS ARE RESTRICTED TO THE IDIOSYNCRATIC PROPERTIES 40 OF LEXICAL ITEMS Every language has thousands of lexical items. But nobody entertained the possibility that every lexical item might be a locus for parametric variation. So P2A gave way to P2B: Parameters are tied to the inflectional system. P2B: PARAMETERS ARE RESTRICTED TO THE INFLECTIONAL SYSTEM 41 ‘It is worth concluding this chapter by reiterating the conceptual advantage that reduced all interlanguage variation to the properties of the inflectional system.’ (Borer 1984: 29) The problem is that not all lexical items are part of the inflectional system and not all inflections are lexical. Here Borer took ‘inflectional’ in a pretty broad sense: Case and agreement relations, theta-role assignment, etc. P2B: PARAMETERS ARE RESTRICTED TO THE INFLECTIONAL SYSTEM 42 But even Borer recognized that inflectional parameters could not handle some of the best known cases of parameters — head-order and subjacency, for example. Another important point: for Borer inflectional rules are not provided by UG: ‘If all interlanguage variation is attributable to [the inflectional] system, the burden of learning is placed exactly on that component of grammar for which there is strong evidence of learning: the vocabulary and its idiosyncratic properties. We no longer have to assume that the data to which the child is exposed bear directly on universal principles …’ (Borer 1984: 29) In this view, parametric variation was not only localized, it was idiosyncratically language-particular. P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 43 Borer was writing before the lexical/functional category distinction was elaborated. P2b gradually morphed into P2c: Parameters are associated with functional heads. P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 44 Fukui (1988): The Functional Parameterization Hypothesis posits that only functional elements in the lexicon (that is, elements such as Complementizer, Agreement, Tense, etc.) are subject to parametric variation. Fukui himself exempted ordering restrictions from this hypothesis. P2c is not a simple extension of P2b. There have been countless functional categories proposed that have nothing to do with inflection, no matter how broadly ‘inflection’ is interpreted: adverbs, topic and focus, and so on. P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 45 Confusingly — lexical parameterization and functional-category parameterization are often used interchangeably. I’ll adopt the term ‘microparameter’ to cover all of P2 — the idea that parameterization is localized in functional elements, whether categories or features. Mark Baker has repeatedly stressed that once you adopt the Borer- Chomsky Conjecture you are led inevitably to microparameters. That is, we end up characterizing small points of variation with few if any global effects. This point has been disputed by Roberts and Holmberg, but microparameters seem to entail few of the massive clustering effects associated with macroparameters. P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 46 Chomsky has often asserted that microparameters are necessary in order to solve ‘Plato’s Problem’: ‘Apart from lexicon, [the set of possible human languages] is a finite set, surprisingly; in fact, a one-membered set if parameters are in fact reducible to lexical properties. … How else could Plato’s problem [the fact that we know so much about language based on so little direct evidence — FJN] be resolved?’ (Chomsky 1991: 26) P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 47 There’s a widespread (but not universal!) opinion that microparameters have both conceptual and empirical advantages over macroparameters (Kayne 2000; Roberts and Holmberg 2010; Thornton and Crain 2013): RICHARD KAYNE IAN ROBERTS ANDERS HOLMBERG ROSALIND THORNTON STEPHEN CRAIN P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 48 ARGUMENTS FOR MICROPARAMETERS: • 1. They impose a strong limit on what can vary: Crosslinguistic differences can now be reduced to differences in features. • 2. They restrict learning to the lexicon (which has to be learned anyway). • 3. Microparameters allow ‘experiments’ to be constructed comparing two closely-related variants, to pinpoint the possible degree of variation (Kayne 2000). • 4. Given the finite number of functional categories, we can calculate the number of parameters. P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 49 There are a number of ways that the assumptions of the Minimalist Program have entailed a rethinking of parameters and the division of labour among the various components for the handling of variation. The take away line of the MP is well known: ‘We hypothesize that FLN only includes recursion and is the only uniquely human component of the faculty of language.’ (Hauser, Chomsky, and Fitch 2002: 1569) MARK HAUSER NOAM CHOMSKY TECUMSEH FITCH P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 50 I assume that by ‘recursion’ HCF mean the Merge operation, and not sentential embedding. Under the strictest interpretation of this quote, there’s no place for handling variation in the narrow syntax at all. P2C: PARAMETERS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH FUNCTIONAL HEADS 51 So where would parameterization be in this conception? At the interfaces: P3: Parameters are stated at the interfaces P3a: Parameters are stated at the PF interface P3b: Parameters are stated at the C-I interface P3: PARAMETERS ARE STATED AT THE INTERFACES 52 Under this perspective, lexical items are subject to a process of generalized late insertion of semantic, formal, and morphophonological features after the syntax. All variation is captured at that point. It’s not at all clear how the mechanics of this would work — in particular taking bare unlabelled and featureless trees as input to the PF and C-I. P3: PARAMETERS ARE STATED AT THE INTERFACES 53 It’s also not clear that Chomsky’s position is as strong as Boeckx’s. When you get over the shock value of the recursion-only quote, you realize that for Chomsky there is a lot more to both FLN and/or UG than recursion: ‘UG makes available a set F of features (linguistic properties) and operations CHL … that access F to generate expressions.’ (Chomsky 2000: 100) That would seem to allow for parametric variation to be handled in the journey towards the interfaces. P3: PARAMETERS ARE STATED AT THE INTERFACES 54 In fact, Chomsky has continued to attribute much more to FLN/UG than just recursion: ‘[FLN] includes phonology, formal semantics, the structure of the lexicon (morphology, words), etc., insofar as they are language-specific …’ (Chomsky, Hauser, and Fitch 2005: np) P3: PARAMETERS ARE STATED AT THE INTERFACES 55 As far as parametric variation in the narrow syntax is concerned, Holmberg and Roberts (2014) construct an argument that the differences between answers to yes-no questions in Finnish vs. English/Swedish are not a matter of vocabulary choice or morphological rules, including spell-out rules. Instead, the syntactic construction of the universal structure proceeds quite differently in the two cases, employing Agree and Internal Merge in different ways. P3: PARAMETERS ARE STATED AT THE INTERFACES 56 There has also been some debate as to whether there is parametric variation at the C-I interface. • Some have argued that the idea is inconceivable. P3: PARAMETERS ARE STATED AT THE INTERFACES 57 But for Ramchand and Svenonius (2008) the narrow syntax provides a ‘basic skeleton’ to C-I, but languages vary in terms of how much their lexical items explicitly encode about the reference of variables like T, Asp, and D. GILLIAN RAMCHAND PETER SVENONIUS THE PRINCIPAL PROBLEMS WITH PARAMETERS 58 No macroparameter has come close to working. ‘Microparameter’ is just another word for ‘language-particular rule’. There would have to be hundreds, if not thousands of parameters. Nonparametric differences among languages undercut the entire parametric program. NO MACROPARAMETER HAS COME CLOSE TO WORKING 59 This fact has fuelled the retreat to microparameters. The clustering effects are simply not there: ‘History not been kind to to the Pro-drop Parameter as originally stated.’ (Baker 2008b:352) ‘In retrospect, [subjacency effects] turned out to be a rather peripheral kind of variation. Judgments are complex, graded, affected by many factors, difficult to compare across languages, and in fact this kind of variation is not easily amenable to the general format of parameters …’ (Rizzi 2014: 16) ‘MICROPARAMETER’ IS JUST ANOTHER WORD FOR ‘LANGUAGE-PARTICULAR RULE’ 60 Let’s say that we observe two Italian dialects one with a do-support-like structure and one without. We could posit a microparametric difference between the dialects — maybe one with an attracting feature that leads to do-support and one that doesn’t. But how does that differ in substance from saying that one dialect has a rule of do-support that the other one lacks? ‘MICROPARAMETER’ IS JUST ANOTHER WORD FOR ‘LANGUAGE-PARTICULAR RULE’ 61 ‘Thirty years ago, if some element moved in one language but not in another, a movement rule would be added to one language but not to the other. Today, a feature ‘I want to move’ (‘EPP’, ‘strength’, etc.) is added to the elements of one language but not of the other. In both cases, variation is expressed by stipulating it. Instead of a theory, we have brute force markers.’ (Starke 2014: 140) MICHAL STARKE THERE WOULD HAVE TO BE HUNDREDS, IF NOT THOUSANDS, OF PARAMETERS 62 Tying parameters to functional categories was a strong conjecture when it was proposed, since there were so few functional categories. And early quotes reflected that idea: There are just ‘a few mental switches’ (Pinker 1994: 112) STEVEN PINKER THERE WOULD HAVE TO BE HUNDREDS, IF NOT THOUSANDS, OF PARAMETERS 63 There are about 30 to 40 parameters (Lightfoot 1999: 259) DAVID LIGHTFOOT THERE WOULD HAVE TO BE HUNDREDS, IF NOT THOUSANDS, OF PARAMETERS 64 ‘There are only a few parameters’ (Adger 2003: 16) DAVID ADGER There are between 50 and 100 parameters (Roberts and Holmberg 2005) THERE WOULD HAVE TO BE HUNDREDS, IF NOT THOUSANDS, OF PARAMETERS 65 Janet Fodor (2001) observes that ‘it is standardly assumed that there are fewer parameters than there are possible rules in a rule based framework; otherwise, it would be less obvious that the amount of learning to be done is reduced in a parametric framework’. JANET D. FODOR THERE WOULD HAVE TO BE HUNDREDS, IF NOT THOUSANDS, OF PARAMETERS 66 Are there fewer parameters than rules? I doubt it. There has never been a consensus on any small set. Hundreds and hundreds of parameters have been proposed. THERE WOULD HAVE TO BE HUNDREDS, IF NOT THOUSANDS, OF PARAMETERS 67 Gianollo, Guardiano, and Longobardi (2008) propose 47 parameters for DP alone on the basis of 24 languages [[only 5 are non-IE, representing only 3 families]]. Longobardi and Guardiano (2011) up the total to 63 binary parameters in DP. GIUSEPPI LONGOBARDI THERE WOULD HAVE TO BE HUNDREDS, IF NOT THOUSANDS OF PARAMETERS 68 One way to get around this problem would be to posit non-parametric differences among languages, thereby keeping a small number of parameters. The problem is that nonparametric differences undercut the entire parametric program. NONPARAMETRIC DIFFERENCES AMONG LANGUAGES UNDERCUT THE ENTIRE PARAMETRIC PROGRAM 69 Are all morphosyntactic differences among languages due to differences in parameter setting? Generally that has been assumed not to be the case. Outside of core grammar are: ‘… borrowings, historical residues, inventions, and so on, which we can hardly expect to — and indeed would not want to — incorporate within a principled theory of UG’ (Chomsky 1981: 8-9) NONPARAMETRIC DIFFERENCES AMONG LANGUAGES UNDERCUT THE ENTIRE PARAMETRIC PROGRAM 70 In other words, from the beginning it has been assumed that some language-particular features are products of extraparametric language particular rules. There are many examples (word order in Hixkaryana; picture noun reflexives and preposition stranding in English; etc.) If all syntactic differences were to be handled by a difference in parameter setting, then, extrapolating to all of the syntactic distinctions in the world’s languages, there would have to be thousands — if not millions — of parameters. That’s obviously an unacceptable conclusion. NONPARAMETRIC DIFFERENCES AMONG LANGUAGES UNDERCUT THE ENTIRE PARAMETRIC PROGRAM 71 And then there’s PF syntax: Some syntactic phenomena that have been attributed to PF: a. extraposition and scrambling (Chomsky 1995) b. object shift (Holmberg 1999; Erteschik-Shir 2005) c. head movements (Boeckx and Stjepanovic 2001) d. the movement deriving V2 order (Chomsky 2001) e. linearization (i.e. VO vs. OV) (Chomsky 1995; Takano 1996; Fukui and Takano 1998; Uriagereka 1999) NONPARAMETRIC DIFFERENCES AMONG LANGUAGES UNDERCUT THE ENTIRE PARAMETRIC PROGRAM 72 f. Wh-movement (Erteschik-Shir 2005) NOMI ERTISCHIK-SHIR NONPARAMETRIC DIFFERENCES AMONG LANGUAGES UNDERCUT THE ENTIRE PARAMETRIC PROGRAM 73 Nobody has any clear idea about which syntactic differences should be considered parametric and which should not be. Needless to say, if learners need to learn rules anyway, nothing is gained by positing parameters. MINIMALISM AND PARAMETERS 74 In standard approaches to both macro- and microparameters, the possible parameters and their possible settings are part of innate UG. That idea is utterly incompatible with the minimalist program: ‘… if minimalists are right, there cannot be any parameterized principles, and the notion of parametric variation must be rethought.’ (Boeckx 2011: 206) MINIMALISM AND PARAMETERS 75 ‘Minimalism is probably not the best framework to investigate parameters …’ First, because theoretical apparatus has been reduced to a minimum, second because the Galilean style has replaced interest in variation (Gallego 2011: 550). ANGEL GALLEGO MINIMALISM AND PARAMETERS 76 Well, all of this is part of what one might call the ‘Galilean style’: the dedication to finding understanding, not just coverage. Coverage of phenomena itself is insignificant’. (Chomsky 2002: 102) Accounting for variation was at the heart of GB. Now it has become ‘insignificant’. P4: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. MUCH OF VARIATION IS A ‘THIRD FACTOR’ EFFECT 77 Chomsky’s three factors in language design: 1. Genetic endowment 2. Experience 3. Principles not specific to the faculty of language The lack of a place for parameters in ‘1. Genetic endowment’ has led researchers to look to 2. and to 3. as a locus for language variation. But 2. has often been taken to mean language-particular and hence uninteresting. So there has been a concerted effort to resituate parameters in principles not specific to language — least-effort and other principles of efficient computation, processing principles, and the like. P4: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. MUCH OF VARIATION IS A ‘THIRD FACTOR’ EFFECT 78 One obvious advantage to this is that not all third- factor effects translate neatly into parameters. That is particularly true for the sorts of crosslinguistic hierarchies proposed mainly in functionalist work. P4: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. MUCH OF VARIATION IS A ‘THIRD FACTOR’ EFFECT 79 Prepositional Noun Modifier Hierarchy (PrNMH): (Hawkins 1983): If a language allows long elements to intervene between a preposition and its object, then it allows short elements. JOHN A. HAWKINS P4: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. MUCH OF VARIATION IS A ‘THIRD FACTOR’ EFFECT 80 It is far from clear how this generalization might be captured by means of parameters, whether macroparameters or microparameters. The same point could be made for other functionally-motivated hierarchies. So let’s look at three ‘third factor’ approaches to parameters. Following the terminology used by Colin Phillips in his work on island constraints and processing, I’ll call the first two ‘grounded approaches’ and ‘reductionist approaches’. I’ll then move to the third type — epigenetic approaches. P4A: GROUNDED APPROACHES 81 A grounded approach is one in which some principle of UG is grounded in — that is, ultimately derived from — some third-factor consideration. A long tradition points to a particular constraint, often an island constraint, and posits that it is a grammaticalized processing principle. P4A: GROUNDED APPROACHES 82 Two examples from Fodor (1978): The XX Extraction Constraint (XXEC): If at some point in its derivation a sentence contains a sequence of two constituents of the same formal type, either of which could be moved or deleted by a transformation, the transformation may not apply to the first constituent in the sentence. The Nested Dependency Constraint (NDC): If there are two or more filler-gap dependencies in the same sentence, their scopes may not intersect if either disjoint or nested dependencies are compatible with the well-formedness conditions of the language. P4A: GROUNDED APPROACHES 83 Another example is the Final Over Final Constraint (FOFC), proposed in Holmberg (2000): One consequence: There are COMP-TP languages that are verb-final, but there are no TP-COMP languages that are verb initial. P4A: GROUNDED APPROACHES 84 Holmberg and his colleagues interpreted this constraint as a parameterizable UG principle. Walkden (2009) points out that the FOFC is accounted for by Hawkins’ processing theory and proposes to build FOFC directly into UG. GEORGE WALKDEN In fact, Mobbs (2014) builds practically all of Hawkins’s parsing theory into UG. IAIN MOBBS P4A: GROUNDED APPROACHES 85 So in this view there are no parameters per se. A UG principle is ‘grounded’ in a parsing principle. And the UG principle itself is underspecified enough to allow for the necessary degree of variation. P4B: REDUCTIONIST APPROACHES 86 A reductionist approach totally removes from UG the burden of accounting for some phenomenon. Rather some ‘third factor’ does all the work. P4B: REDUCTIONIST APPROACHES 87 Returning to the FOFC, Trotzke, Bader, and Frazier (2013) provide evidence that a better motivated account is to remove it entirely from the grammar, since it can be explained in its entirety by systematic properties of performance systems. ANDREAS TROTZKE MARKUS BADER LYN FRAZIER P4B: REDUCTIONIST APPROACHES 88 They also deconstruct the Head-Complement parameter in a similar fashion. ‘[T]he physics of speech, that is, the nature of the articulatory and perceptual apparatus require one of the two logical orders, since pronouncing or perceiving the head and the complement simultaneously is impossible. Thus, the head-complement parameter, according to this approach, is a third-factor effect.’ (Trotzke, Bader, and Frazier 2013: 4) Which option is chosen has to be built into the grammar of individual languages. P4B: REDUCTIONIST APPROACHES 89 Another example: Kayne (1994) provided an elaborate UG-based explanation of why rightward movement is so restricted in language after language. Ackema and Neeleman (2002) argue that the apparent ungrammaticality of certain syntactic structures should not be accounted for by syntax proper (that is, by the theory of competence), but rather by the theory of performance. The latter acts as a filter on possible linguistic representations. P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 90 In an epigenetic approach to variation, parameters are not provided by an innate UG. Rather, parametric effects arise in the course of the acquisition process through the interaction of certain third-factor learning biases and experience. UG creates the space for variation by leaving certain features underspecified. One could also call this an ‘emergentist’ view of parameters. P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 91 There are several proposals along these lines: Gianollo, Guardiano, and Longobardi (2008) Boeckx (2011) Biberauer, Holmberg, Roberts, and Sheehan (2014) (preceded by many papers by the same four authors) P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 92 I’ll focus on Biberauer et al. THERESA BIBERAUER MICHELLE SHEEHAN P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 93 There are no parameters per se — all variation arrives through the acquisition process guided by some third factor assumptions about learning. The child is conservative in the complexity of the formal features that it assumes are needed (Feature Economy) and liberal in its preference for particular features to extend beyond the input (Input Generalization – Superset Bias). The idea is that these principles drive acquisition and thus render parameters unnecessary, while deriving the same effects. P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 94 Here’s their word order hierarchy: P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 95 Let’s say that a language is consistently head-initial except in NP, where the noun follows its complements. However, there is a definable class of nouns in this language that do precede their complements. And a few nouns in this language behave idiosyncratically in terms of the positioning of their specifiers and complements. P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 96 In their theory, the child will go through the following stages of acquisition, zeroing in step-by-step on the adult grammar: 1. First s/he will assume that ALL phrases are headinitial, even noun phrases. 2. Next s/he will assume that ALL NPs are head-final 3. Next s/he will learn the class of exceptions to 2. 4. Finally, s/he will learn the purely idiosyncratic exceptions. Other hierarchies are more complex — they depend on many assumptions about the feature content of particular categories. P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 97 P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 98 There a lot of questions that one can ask about this scenario. Most importantly — is this really the way language acquisition works in real life? Do children go from general to the particular, correcting themselves as they go, gradually zeroing in on the correct grammar? There’s a lot of disagreement among acquisitionists — many argue for precisely the reverse set of steps. P4C: EPIGENETIC APPROACHES 99 Biberauer et al. themselves agree that these steps can be overridden: (a) The early stages may correspond to a pre- production stage (cf. Wexler's very early parameter setting). (b) It is possible that acquirers pass through certain stages very quickly as the counterevidence is so readily available. (c) Frequency effects can distort the smooth transition through the hierarchies. P4B: REDUCTIONIST APPROACHES 100 The second question is how much the child has to know in advance of beginning the entire process. For example, the child has to know to ask ‘Are unmarked phi- features fully specified on some probes?’ That implies a lot of grammatical knowledge. Where does this knowledge come from and how do they match this knowledge with the input? Still, this is a challenging approach that needs to be taken very seriously. P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 101 The microparametric approach to variation has a kernel of reasonableness to it. Even closely related speech varieties can vary from each other in many details. Microparameters capture this fact. But why call them ‘microparameters’? Why not just ‘rules’? P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 102 Of course, I know why there has been resistance to that. ‘Rules’ brings back the ghosts of pre-generative structuralism, where it was believed by many that languages could differ from each other without limit. And they bring back the spectre of early transformational grammar, where grammars were essentially long lists of rules. P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 103 But to call a rule a rule is not to imply that anything can be a rule. Possible rules are still constrained by UG. What’s in UG? Obviously the Merge operation or something analogous — but there’s a lot more than that. P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 104 It’s hard for me to see how the broad architecture of the grammar could be learned inductively, for example. For example, there is very little evidence that the syntax can have access to the segmental phonology. There’s no language with a rule that says that displacement — Internal Merge, if you will — targets only those elements with front vowels, for example. I have no trouble attributing that fact to UG. P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 105 But the biggest constraint on what can be a rule derives from processing. No language has a rule that lowers a filler exactly two clauses deep, leaving a gap in initial position. In keeping with the distinction between what is possible and what is probable, I would say that such a rule, while theoretically possible, is so improbable (for processing reasons) that it will never occur. I first put forward a proposal like this in my 2005 book. P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 106 A quote from Norbert Hornstein that captures the essence of my view of variation: NORBERT HORNSTEIN P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 107 ‘There is no upper bound on the ways that languages might differ though there are still some things that grammars cannot do. A possible analogy for this conception of grammar is the variety of geometrical figures that can be drawn using a straight edge and compass. There is no upper bound on the number of possible different figures. However, there are many figures that cannot be drawn (e.g. there will be no triangles with 20 degree angles). … P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 108 Similarly, languages may contain arbitrarily many different kinds of rules depending on the PLD they are trying to fit. However, none will involve binding relations in which antecedents are c-commanded by their anaphoric dependents or where questions are formed by lowering a Wh-element to a lower CP. Note that this view is not incompatible with languages differing from one another in various ways.’ (Hornstein 2009: 167) P5: PARAMETERS ARE NOT PART OF UG. LANGUAGES DIFFER FROM EACH OTHER IN TERMS OF THE RULES THAT THEY POSSESS. POSSIBLE RULES ARE CONSTRAINED BY BOTH UG AND ‘THIRD FACTOR’ CONSIDERATIONS 109 I’ll be the first to admit that this approach is in some ways a retreat from the marvellous vision presented in Lectures in Government and Binding in 1981. But we all agree that it’s better to start with the most ambitious vision possible and to retreat from that when necessary, than to think small and to stay small. Still the idea that a grammar is composed of language-particular rules constrained by both UG principles and third-factor principles hardly represents a defeat. I personally find it an appealing vision that promises to inform research on crosslinguistic variation in the years to come. 110 THANK YOU!