Presentation Package

advertisement

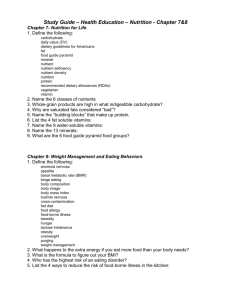

chapter Nutritional 10 Factors in Health and Performance Nutritional Factors in Health and Performance Kristin Reimers, PhD, RD Chapter Objectives • Identify the protein, carbohydrate, and fat recommendations for athletes. • Discern between dietary recommendations for disease prevention and recommendations for performance. • Identify and apply appropriate hydration practices for athletes. • Apply precompetition and posttraining eating strategies and advise athletes on guidelines for weight gain and weight loss. (continued) Chapter Objectives (continued) • Recognize signs and symptoms of eating disorders. • Understand the importance of having an intervention and referral system in place for athletes suspected of having an eating disorder. • Recognize the prevalence and etiologies of obesity. • Assist in the assessment process for obese individuals. Section Outline • Role of the Nutritionist Role of the Nutritionist • Responsibilities of the nutritionist include the following: – Personalized nutritional counseling: weight loss and weight gain, strategies to improve performance, menu planning, dietary supplements – Dietary analysis of food records – Nutritional education: presentations and handouts – Referral and treatment of eating disorders Section Outline • How to Evaluate the Adequacy of the Diet – Standard Nutrition Guidelines – Dietary Reference Intakes How to Evaluate the Adequacy of the Diet • Standard Nutrition Guidelines – Most athletes have two basic dietary goals: • Eating to maximize performance • Eating for optimal body composition How to Evaluate the Adequacy of the Diet • Standard Nutrition Guidelines – Food Guide Pyramid • Used to evaluate appropriate calorie level • Used to evaluate appropriate nutrient levels to prevent nutrient deficiency or toxicity • Developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1992 • Updated to MyPyramid in 2005 MyPyramid • Figure 10.1 (next slide) – Displays recommended types and amounts of food to eat daily – For more information and resources, go to www.mypyramid.gov Figure 10.1 How to Evaluate the Adequacy of the Diet • Standard Nutrition Guidelines – The color bands of MyPyramid represent five food groups that are needed each day for health: • • • • • Grains Vegetables Fruits Milk Meat and beans Key Point • MyPyramid is an excellent starting point from which to evaluate the adequacy of an athlete’s diet. If a diet provides a variety of foods from each group, it is likely adequate for vitamins and minerals. However, if the diet excludes an entire food group, specific nutrients may be lacking. Table 10.1 How to Evaluate the Adequacy of the Diet • Dietary Reference Intakes – In 2005, the DRIs replaced the “Recommended Dietary Allowances.” – The DRI for each nutrient includes the following: • Estimated average requirement and its standard deviation by age and gender • Recommended dietary consumption based on the estimated average requirement • An adequate intake level when a recommended intake cannot be based on an estimated average requirement • Tolerable upper intake levels above which risk of toxicity increases Section Outline • Macronutrients – Protein • Structure and Function of Proteins • Dietary Protein • Protein Requirements – General Requirements – Increased Requirements for Athletes (continued) Section Outline (continued) • Macronutrients – Carbohydrates • • • • • Structure and Sources of Carbohydrates Dietary Carbohydrate Glycemic Index Fiber Carbohydrate Requirements – Lipids • • • • Structure and Function of Lipids Fat and Disease Fat Requirements and Recommendations Fat and Performance Macronutrients • A macronutrient is a nutrient that is required in significant amounts in the diet. • Three important classes of macronutrients are protein, carbohydrates, and lipids. Macronutrients • Protein – Structure and Function of Proteins • More than half of the amino acids can be synthesized by the human body and are commonly called “nonessential” amino acids because they do not need to be consumed in the diet. • Nine of the amino acids are “essential” because the body cannot manufacture them and therefore they must be obtained through the diet. • Proteins provide 4 kcal/g. Table 10.2 Macronutrients • Protein – Dietary Protein • high-quality (complete) protein: A protein with an amino acid pattern similar to that needed by the body. Usually of animal origin. • low-quality (incomplete) protein: A protein that is deficient in one or more of the essential amino acids. Usually of plant origin. Macronutrients • Protein – Protein Requirements • General Requirements – Assuming that caloric intake is adequate and that two-thirds or more of the protein is from animal sources, the recommended intake for protein for adults is 0.8 g/kg (0.36 g/pound) of body weight for both men and women. – Expressed as a percent of daily caloric intake, a common protein intake recommendation is 10% to 15%. Key Point • Recommendations to increase or decrease protein intake should be made on an individual basis after the normal diet has been analyzed and caloric intake considered. A mixed diet is the best source of high-quality protein. Strict vegetarians must plan their diet carefully to ensure an adequate intake of all essential amino acids. Macronutrients • Protein – Protein Requirements • Increased Requirements for Athletes – Based on current research, it appears that the protein requirements for athletes are between 1.5 and 2.0 g/kg of body weight, assuming that caloric intake and protein quality are adequate. Macronutrients • Carbohydrates – The primary role of carbohydrate in human physiology is to serve as an energy source. – Carbohydrates provide 4 kcal/g. Macronutrients • Carbohydrates – Structure and Sources of Carbohydrates • Monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, and galactose) are single-sugar molecules. • Disaccharides (sucrose, lactose, and maltose) are composed of two simple sugar units joined together. • Polysaccharides, also known as complex carbohydrates, contain up to thousands of glucose units. Macronutrients • Carbohydrates – Dietary Carbohydrate • All types of dietary carbohydrate—sugars as well as starches—are effective in supplying the athlete with glucose and glycogen. • Consumption of a mix of sugars and starches is desirable. Macronutrients • Carbohydrates – Glycemic Index • The GI classifies a food by how high and for how long it raises blood glucose. • The reference food is glucose or white bread (GI = 100). • Foods that are digested quickly and raise blood glucose (and insulin) rapidly have a high GI. • Foods that take longer to digest and thus slowly increase blood glucose (and therefore stimulate less insulin) have a low GI. Glycemic Index (GI) of Various Foods • Table 10.3 (next slide) – The table uses white bread (GI = 100) as a standard. – When variations exist in a food item, the mean is reported. Table 10.3 Adapted, by permission, from Foster-Powell, Holt, and Brand-Miller, 2002. Macronutrients • Carbohydrates – Fiber • The DRI for fiber is 38 and 25 g/day for young men and women, respectively. • This level of fiber may be excessive for some aerobic endurance athletes. – Carbohydrate Requirements • The general recommendation is to consume 50% to 55% of total daily calories as carbohydrate. • Aerobic endurance athletes who train for long durations (90 minutes or more daily) should replenish glycogen levels by consuming maximal levels of carbohydrate, approximately 8 to 10 g/kg of body weight. Key Point • Some aerobic endurance athletes have maximal carbohydrate requirements, up to 10 g/kg per day. Most athletes do not deplete muscle glycogen on a daily basis, however, and therefore have lower carbohydrate requirements. Macronutrients • Lipids – Structure and Function of Lipids • Fatty acids containing no double bonds are saturated. • Fatty acids containing one double bond are monounsaturated. • Fatty acids containing two or more double bonds are polyunsaturated. • Fats provide approximately 9 kcal/g. Macronutrients • Lipids – Fat and Disease • High levels of cholesterol or unfavorable ratios of lipoproteins are associated with increased risk of heart disease. • High levels of HDLs protect against heart disease. • HDLs can be increased by exercise and weight loss. Table 10.4 Macronutrients • Lipids – Fat Requirements and Recommendations • The recommendation for the general public from health organizations such as the American Heart Association is that fat should constitute 30% or less of the total calories consumed. • It is recommended that 20% of the total calories (or twothirds of the total fat intake) come from monounsaturated or polyunsaturated sources and 10% from saturated fats (onethird of total fat intake). (continued) Macronutrients • Lipids – Fat Requirements and Recommendations (continued) • The Sub-Committee on Nutrition of the United Nations recommends an upper limit for fat intake of 35% of total calories for active people. • The American Heart Association and the Sub-Committee on Nutrition of the United Nations recommend that fat provide at least 15% of the total calories in the diets of adults and at least 20% of total calories in the diets of women of reproductive age. Key Point • Fat phobia, or fear of eating fat, can lead to nutrient deficiencies, which harm performance. Athletes who eat very little or no fat should receive nutritional counseling and information. Macronutrients • When Should Athletes Decrease Dietary Fat? – Need to increase carbohydrate intake to support training type • In this case, to ensure adequate protein provision, fat is the nutrient of choice to decrease so that that caloric intake can remain similar while carbohydrate is increased. Macronutrients • When Should Athletes Decrease Dietary Fat? – Need to reduce total caloric intake to achieve weight loss • Because fat is dense in calories and is highly palatable, decreasing dietary fat, if the diet has excess fat, can help reduce caloric intake. – Need to decrease elevated blood cholesterol • Some young athletes are strongly predisposed to heart disease, although this is uncommon. Macronutrients • Lipids – Fat and Performance • Intramuscular fatty acids are more important during activity. • Circulating fatty acids (from adipose tissue or diet) are more important during recovery. • Consumption of high-fat diets may enhance performance and result in longer distance to exhaustion. • The effects of high-fat diets vary, depending on the individual. Section Outline • Micronutrients – Vitamins – Minerals • Iron • Calcium Micronutrients • A micronutrient is a nutrient that is required in small amounts (typically measured in milligram—or even smaller—quantities) in the diet. • Two primary types of micronutrients are vitamins and minerals. Micronutrients • Vitamins – Vitamins are organic substances (i.e., containing carbon atoms) that cannot be synthesized by the body. – They are needed in very small amounts and perform specific metabolic functions. Table 10.5 (continued) (continued) Table 10.5 (continued) Micronutrients • Minerals – Minerals are required for a wide variety of metabolic functions. – For athletes, minerals are important for bone health, oxygen-carrying capacity, and fluid and electrolyte balance. Table 10.6 (continued) Table 10.6 (continued) (continued) Micronutrients • Minerals – Iron • Iron is a constituent of hemoglobin and myoglobin and, as such, plays a role in oxygen transport and utilization of energy. Micronutrients • Minerals – Calcium • Athletes who consume low-calcium diets may be at risk for osteopenia and osteoporosis (deterioration of bone tissue leading to increased bone fragility and risk of fracture). Section Outline • Fluid and Electrolytes – Water • Fluid Balance • Risks of Dehydration • Monitoring Hydration Status – Electrolytes – Fluid Replacement • Before Activity • During Activity • After Activity Fluid and Electrolytes • Water – Water is the largest component of the body, representing from 45% to 70% of a person’s body weight. – Total body water is determined largely by body composition; muscle tissue is approximately 75% water, whereas fat tissue is about 20% water. Fluid and Electrolytes • Water – Fluid Balance • The average fluid requirement for adults is estimated to be 2 to 2.7 quarts (1.9-2.6 L) per day. • Athletes sweating profusely for several hours per day may need to consume an extra 3 to 4 gallons (11-15 L) of fluid to replace losses. Fluid and Electrolytes • Water – Risks of Dehydration • Fluid loss equal to as little as 1% of total body weight can be associated with an elevation in core temperature during exercise. • Fluid loss of 3% to 5% of body weight results in cardiovascular strain and impaired ability to dissipate heat. • At 7% loss, collapse is likely. Key Point • Consuming adequate fluids before, during, and after training and competition is essential to optimal resistance training and aerobic endurance exercise. Fluid and Electrolytes • Water – Monitoring Hydration Status • Each pound (0.45 kg) lost during practice represents 1 pint (0.5 L) of fluid loss. • Signs of dehydration include the following: – – – – Dark yellow, strong-smelling urine Decreased frequency of urination Rapid resting heart rate Prolonged muscle soreness Fluid and Electrolytes • Electrolytes – The major electrolytes lost in sweat are sodium chloride, and, to a lesser extent, potassium. • Fluid Replacement – The ultimate goal is to start exercise in a hydrated state, avoid dehydration during exercise, and rehydrate before the next training session. Fluid and Electrolytes • Fluid Replacement Guidelines – Before a Training Session • Encourage athletes to hydrate properly before prolonged exercise in a hot environment. • Intake should be approximately 16 fluid ounces (0.5 L) of a cool beverage 2 hours before a workout. Fluid and Electrolytes • Fluid Replacement Guidelines – During a Training Session • Provide cool beverages (about 50-70 °F [10-21 °C]). • Have fluids readily available, since the thirst mechanism does not function adequately when large volumes of water are lost. • Athletes need to be reminded to drink. • Athletes should drink fluid frequently—for example, 6 to 8 fluid ounces (177-237 ml) every 15 minutes. Fluid and Electrolytes • Fluid Replacement Guidelines – After a Training Session • Athletes should replenish fluids with at least 1 pint (0.5 L) of fluid for every pound (0.45 kg) of body weight lost. • Weight should be regained before the next workout. • Water is an ideal fluid replacement, although flavored beverages may be more effective at promoting drinking. • The ideal fluid replacement beverage depends on the duration and intensity of exercise, environmental temperature, and the athlete. Section Outline • Precompetition and Postexercise Nutrition – Precompetition Food Consumption • • • • Purpose Timing Practical Considerations Carbohydrate Loading – Postexercise Food Consumption Precompetition and Postexercise Nutrition • Precompetition Food Consumption – Purpose • The primary purpose is to provide fluid and energy for the athlete during the performance. – Timing • The most common recommendation is to eat 3 to 4 hours prior to the event to avoid becoming nauseated or uncomfortable during competition. Precompetition and Postexercise Nutrition • Precompetition Food Consumption – Practical Considerations • It is important for athletes to consume food and beverages that they like, that they tolerate well, that they are used to consuming, and that they believe result in a winning performance. Key Point • The primary goal of the precompetition meal is to provide fluid and energy for the athlete during performance. Precompetition and Postexercise Nutrition • Precompetition Food Consumption – Carbohydrate Loading • Carbohydrate loading is a technique used to enhance muscle glycogen prior to long-term aerobic endurance exercise. Precompetition and Postexercise Nutrition • Postexercise Food Consumption – Data suggest that high-GI foods consumed after exercise replenish glycogen faster than low-GI foods. – Although emphasis is usually placed on carbohydrate, in practical terms, consuming a balanced meal ensures the availability of all substrates for adequate recovery, including amino acids. Section Outline • Weight and Body Composition – Energy Requirements • Factors Influencing Energy Requirements • Estimating Energy Requirements – Weight Gain – Weight Loss – Rapid Weight Loss Weight and Body Composition • Energy Requirements – Energy is commonly measured in kilocalories (kcal or calories). – A kilocalorie is the work or energy required to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water 1 °C (or 2.2 pounds of water 1.8 °F). – Energy (caloric) requirement is defined as energy intake equal to expenditure, resulting in constant body weight. Weight and Body Composition • Energy Requirements – Factors Influencing Energy Requirements • Resting metabolic rate • Thermic effect of food • Physical activity Key Point • There is a wide range of energy expenditures and energy intakes among sports due to differences in body mass, intensity of training, work efficiency, and the size of the involved muscle mass. Weight and Body Composition • Energy Requirements – Estimating Energy Requirements • Energy needs can be loosely estimated using the guidelines found in table 10.7. • Athletes can also use food diaries during periods of stable body weight to estimate requirements. Table 10.7 Weight and Body Composition • Weight Gain – If all the extra calories consumed are used for muscle growth during resistance training, then about 2,500 extra kilocalories are required for each 1-pound (0.45 kg) increase in lean tissue. Key Point • Gains in body mass and strength occur when the athlete consumes adequate calories and dietary protein and engages in a progressive resistance training program. Weight and Body Composition • Weight Loss – If all the expended or dietary-restricted kilocalories apply to body fat loss, then a deficit of 3,500 kcal will result in a 1-pound (0.45 kg) fat loss. – The maximal rate of fat loss appears to be approximately 1% of body mass per week. – This is an average of 1.1 to 2.2 pounds (0.5-1.0 kg) per week and represents a daily caloric deficit of approximately 500 to 1,000 kcal. Key Point • The most important goal for weight loss is to achieve a negative calorie balance. Therefore, the types of foods the individual consumes are less important than the portions of those foods. The focus is on calories. Weight and Body Composition • Rapid Weight Loss – For athletes who desire to minimize lean tissue loss, small decreases in caloric intake to achieve gradual weight loss are indicated. Section Outline • Eating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa – Definitions and Criteria – Management and Care • Steps in the Management of Eating Disorders • What Not to Do Eating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa • Definitions and Criteria – Anorexia nervosa is self-imposed starvation in an effort to lose weight and achieve thinness. – Bulimia nervosa is characterized by recurrent consumption of food in amounts significantly greater than would customarily be consumed at one sitting. Figure 10.2 Reprinted, by permission, from American Psychiatric Association, 1994. Figure 10.3 Reprinted, by permission, from American Psychiatric Association, 1994. Eating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa • Definitions and Criteria – Warning Signs for Anorexia Nervosa • Commenting repeatedly about being or feeling fat • Asking questions such as “Do you think I’m fat?” when weight is below average • Dramatic weight loss for no medical reason • Reaching a weight that is below the ideal competitive weight • Continuing to lose weight even during the off-season • Preoccupation with food, calories, and weight Eating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa • Definitions and Criteria – Warning Signs for Bulimia • Eating secretively • Disappearing repeatedly immediately after eating • Appearing nervous if something prevents the person from being alone after eating • Losing or gaining extreme amounts of weight • Smell or remnants of vomit in the rest room or elsewhere • Disappearance of large amounts of food Eating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa • Definitions and Criteria – Warning Signs for Both Disorders • • • • • • • • Complaining frequently of constipation or stomachaches Mood swings Social withdrawal Relentless, excessive exercise Excessive concern about weight Strict dieting followed by binges Increasing criticism of one’s body Strong denial that a problem exists even when there is hard evidence Eating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa • Management and Care – Steps in the Management of Eating Disorders • • • • Fact finding Confronting Referring Following up Eating Disorders: Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa • Management and Care – What Not to Do • The strength and conditioning professional’s job is not to treat an eating disorder; it is to be aware of warning signs and to refer when a problem is suspected. Section Outline • Obesity Table 10.8 Key Point • Obesity is not the same condition in each individual. Thorough assessment helps determine which treatment is appropriate and, more important, whether the individual is ready for treatment.