eng-310-unit-plan

advertisement

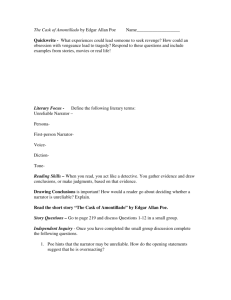

Nicole Willekes English 310- 02 November 30, 2012 Comprehensive Unit Plan Genre: Short stories Grade level: 12th grade Examples of short stories: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. “20/20” by Linda Brewer “The Jewelry” by Guy de Maupassant “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe “Recitatif” by Toni Morrison “A Wall of Fire Rising” by Edwidge Danticat “A & P” by John Updike Backwards Design: Preliminary Plan Stage 1- Desired Results Established Goals: - - Students will be able to produce a short story, “making conscious choices regarding language, form, and style.” Standard 1.5 Students will thoughtfully analyze and study mentor texts and example literature. Standard 2.1 Students will be able to use writing strategies to create “meaning beyond the literal level (e.g., drawing inferences; confirming and correcting; making comparisons, connections, and generalizations; and drawing conclusions).” Standard 2.2 Students will “understand and use the English language effectively” in composing their own short stories. Standard 4.1 Based on MI HSCE, English Language Arts. - Students will be able to “write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences. a. Engage and orient the reader by setting out a problem, situation, or observation and its significance, establishing one or multiple point(s) of view, and introducing a narrator and/or characters; create a smooth - progression of experiences or events. b. Use narrative techniques, such as dialogue, pacing, description, reflection, and multiple plot lines, to develop experiences, events, and/or characters.” W.12.3a/3b Students will be able to “develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific purpose and audience.” W.12.5 Based on CCSS, English Language Arts Essential Questions: - How does one create narrative prose? How are the elements of a narrative (characters, setting, etc…) deepened and made realistic to a reader? What can novice writers learn about the process of drafting short stories from a mentor short story? Understanding: Students will understand that… - The plot in narrative writing must be sequenced and shaped in a way that engages an audience and shapes their story. Narration and point of view must be given substantial consideration when writing with style, tone, and voice. Characters need to be well-developed and realistic. Setting can set the situation, mood, and even character, as well as set the stage for foreshadowing, symbolism and other literary devices. Symbolism can turn narrative prose into a metaphorical treasure hunt by deepening the story into multiple, rich layers for the reader’s interpretation. Knowledge: Students will know… - The elements of a good narrative are plot, narration and point of view, characters, setting, and symbolism. The process one puts into composing a narrative consists of extensive planning, revising, editing, and rewriting. Ability: Students will be able to… - Compose narratives using the elements learned throughout the unit. Make these elements believable and realistic. Proofread, revise, and edit multiple drafts of a narrative. Read mentor texts analytically, annotate, and apply observed concepts. Stage 2- Assessment Evidence Performance Tasks: - Write, proofread, revise, and edit a short story Read and annotate mentor texts Respond to peer work Other evidence: - Journal entries Class discussion Group discussion (Literature circles) Stage 3- Learning Plan Learning Activities: WHERETO W: This design will help students know WHERE the unit is going by giving them preliminary activities, such as reading short stories out loud and for homework. They will know WHAT is expected by examining mentor texts closely, studying the literary devices and techniques that established writers used to write short stories. The teacher will know WHERE the students are coming from by asking for reflective writing in their journals after various class periods. H: This design will HOOK all students and HOLD their interest by exploring previously published short stories with engaging plots, characters, settings, and themes. They will be asked to replicate literary devices and compose, drawing them into the unit and holding their interest with the principle of choice as the great motivator: students will able to choose any topic they wish for their own short story. E: This design will EQUIP all students with a knowledge of commonly used and effective literary devices and strategies through the guided instruction of the teacher (annotating mentor texts as a class, learning through writing, and watching the teacher write). The students will EXPERIENCE the key ideas and EXPLORE the issues in their journal writing and in their own short story, which will be the culminating experience in this unit. R: This design will provide opportunities to RETHINK and REVISE their understandings and work through several peer-reviews, one-on-one conferences with the teacher, and individual revising and editing processes. E: This design will allow students to EVALUATE their work and its implications by sharing it with a small group and discovering the effect that it has on an audience. They will be given chances to self-evaluate by being asked to put themselves into someone else’s shoes (ex. “Pretend you are mother with three children, pretend you are a 13-year old, etc…Read your story. React through the mind of another.) T: This design will be TAILORED (personalized) to the different needs, interests, and abilities of all learners by offering a wide and diverse range of mentor texts that the students can connect too. The students will be allowed to choose their topic and theme for their final short story, allowing students to choose topics that they are comfortable in and know about. It also allows higher-achieving learners to challenge themselves by choosing more difficult topics or weaving new and unfamiliar literary strategies into their writing. O: This design will be ORGANIZED to maximize initial and sustained engagement as well as effective learning by alternating the activities to accommodate high school attention spans. Reading and writing will be varied, as well as activities within a “reading day”. Mentor texts chosen will be interesting, unique, and offer many opportunities for analysis on a literal and metaphorical level. Month-Long Calendar of My Unit: Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 MON TUES WED THURS FRI Writing Lesson Plan 1: Intro to short stories. Study “20/20”Writing: What do we notice? Reading “The Jewelry” by Guy de Maupassant Writing Study examples of genre: “The Jewelry”. Writing: Plot READING?? Lesson Plan 2: “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allen Poe Writing How to incorporate plot and other elements we noticed into our writing. Journal writing. Writing How to create colorful, round characters. Journal writing. Writing Lesson plan 3: Demonstrating the writing process Literature circles. Free write. Reading Writing “Recitatif” by Lesson plan 4: Toni Morrison Demonstrating the writing Literature process circles. Free write Writing Lesson plan 5: Hands-on activity (understanding and skill) Reading “A & P” by John Updike Writing Lesson plan 6: Specific mechanics lesson for editing purposes Writing One-on-one conferences w/ teacher. Writing One-on-one conferences w/ teacher. At the same time… At the same time… Group work checking symbolism and characters Group work checking symbolism and characters. Hw:Final Draft Writing Draft short stories Literature circles. Free write Literature circles. Free write. Reading “A Wall of Fire Rising” by Edwidge Danticat Literature circles. Free write Writing Draft short stories Finish draft as homework Presenting: Read short story to class (Peer review for two other classmates) Writing Share short stories within small groups. Check for plot and narration Presenting: Read short story to class (Peer review for two other classmates) Lesson Plan 1: Introduction to Short Stories Week 1, Monday Materials: Journals, pens, copy of Linda Brewer’s 20/20 for all students, Copy of 20/20 for teacher’s overhead projector, whiteboard, markers. Connection (0-2 minutes): “Good morning class! We just finished learning about the genre of poetry a couple of days ago and today we are beginning a journey into a new genre: narrative writing. We will focus on short stories in this unit and towards the end of this unit we will work on composing our own short stories!” Active Engagement (2-20 minutes): “We are going to begin with an immersion into the genre. I want you all to read carefully and notice elements of this short story as you go. Go ahead and get your journals off the shelf for this activity.” Students will know what their journals are; they will have had them for the whole year in this class. Journals always stay in the classroom. “I am going to hand out a short story entitled ‘20/20.’ Some of you may have read this story before. It is a very short piece, but it is loaded with meaning. Read it through once without stopping, and then go back and read it slowly a second time. On your second time around, I want you to write down things that you notice about this short story. For example, tell me something about the characters in this short story. What do you notice about these characters? Don’t forget to put the date at the top right-hand corner of your new journal entry.” Teacher will pass out printed copies of Linda Brewer’s short story, “20/20.” (Handout #1: included at end of unit plan) Students will read as teacher circulates, reading over shoulders, keeping students on track. “Alright class, what did you think of the story?” Teacher will call on a few students. “What did you notice?” Teacher will allow students to share some of the things that they noticed and wrote in their journals. Teacher will put overhead copy of ‘20/20’ up so that all students can see the teacher copy. Teacher will guide and discuss the items that students share while marking the observations on the overhead copy, in order to model annotation of a mentor text for students. If students do not cover all the points, the teacher will bring them up before moving on to the lecture. Following are examples of points that, ideally, students will bring up, and teacher will discuss if they do not: “The plot of “20/20” is very unique. It begins right in the middle of an action, going on a road trip. We see a turning point in the story, which also happens to be Bill’s only piece of dialogue, when he takes over driving. He sees something here that he did not know before. The story ends in the middle of an action, just like the beginning: “Bill decided to let it ride” (Brewer, 21). Who is telling this story? It appears to be someone who is not actually in the story. The narrator refers to the characters in third person and uses the past tense. We also notice some casual language; it almost seems as if Bill is talking. Bill seems to be the main character. The characters are from interesting places: rural Ohio and the East Coast. We notice that Bill seems to be the focal character and the way he judges Ruthie makes him feel superior. He is proud of his ability to argue, while Ruthie is observant. The story is also dependent on setting because the sights that Ruthie sees are humorous because of the unlikely locations: ‘a white buffalo bear Fargo’ (Brewer, 21). There are many points that we can observe about this short story, however, these are all specifics things that we observed about just this one particular story. So let’s talk about short stories in a broader setting than just this one and see if we can put names to some of the concepts we just discussed. What makes up a short story? What are the elements of a good short story? Teaching Point (20-30 minutes): Teacher will give an introduction of short story unit with a mini-lecture which provides a brief overview of the components of a short story. Teacher will write main points on the whiteboard to help the students take notes. “First off, we are going to talk briefly about what a short story is. As we progress through the unit, we will be looking at a variety of short stories that show us all the elements of a good narration. So what makes up a short story? What components go into a good, or well-written short story? There are five main parts of a short story that we are going to focus on. First, we are going to learn about plot and how to recognize this throughout short stories. Plot itself consists of 5 main parts: Exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. The exposition sets the stage for the story. This can be anywhere from one sentence long to multiple paragraphs. It tells us the ‘where’ and ‘when’ and introduces us to our characters. What is the situation? What is the information that we need to make sense of this story? That is what we will learn in as much detail as the author allows through the exposition. The rising action is the ‘building action.’ The story is building up to something big. Maybe the tension is mounting or emotion is growing. Conflict is being introduced in the characters lives. Often we refer to the ‘inciting incident,’ just a fancy term for conflict which has been introduced. The climax is the ‘big moment’ of a story. It is ‘the moment of greatest emotional intensity’ (Booth & Mays, 64). The plot’s outcome and the character’s fate are decided at the climax. Next we have the falling action. The falling action begins to bring the story to a close and moves the plot towards the final resolution. The tension built up at the climax begins to diffuse. Finally, the story ends with the conclusion. The conflict is solved (not always to the satisfaction of the readers) and there is a certain aspect of closure. Often, the conclusion disappoints the characters as well as the readers. So that was a summary of the 5 main parts of a plot. Are there any question regarding this? Ok, great. Secondly, we will focus on narration and point of view. Who is telling the story? Do they know everything? Can they see inside the character’s heads or are they just another character? Point of view is a great place to start. If the story is told from an “I” character, we are getting a first person narrator. A third person narrator gives us the point of view from the outside; all the characters can be referred to in third person (he, she, they, etc…). When speaking of third-person narration, we have a few different types. An omniscient narrator can see inside the characters’ heads and read thoughts and perceptions of these characters. This narrator can also be called an unlimited narrator, and despite its abilities, will often choose to focus on a few characters. A limited narrator cannot read thoughts. These types of narrators usually only have access to one point of view, and may even be a character in the story. We can also encounter an objective narrator, which does not give us insight into any one characters’ head, but rather states things as they are and leaves it to the reader to figure out the rest. Once in awhile, we also encounter the unreliable narrator. For example, the story might be told in first-person because the narrator is a character in the story, but as a human, he or she might stretch the truth, or even lie. Character is my personal favorite element of short stories. Like all the elements that we will study in this unit, characters are extremely important to the life and breathe of every short story. There are so many ways that you can tell about your characters without explicitly stating their characteristics and it is fun to make these inferences as we read a text as well! When we have a character that acts in a manner that is predictable and stereotypical we refer to that as a flat character. The opposite of this would be a round character. A round character is much more complex and has more unpredictable, varied responses than does a flat character. However, we need to remember that sometimes, a flat character can be just as good and memorable as a round character. For example, if we give them one or two individual traits, and for the most part they are a ‘stock’ character, this may stick in the reader’s mind longer than a very complex character (Booth & Mays, 124). Has anyone here ever read Oliver Twist? By Charles Dickens? That is a great example of flat, yet memorable characters. I recommend that book to all of you. Another way we can classify characters is by whether or not they are dynamic or static. A dynamic character is one that changes through the course of the story. A static character will remain the same; uninfluenced by the events or experiences that the story presents. Our fourth main element for this unit is symbolism. Incorporating symbolism into a story can enhance the depth and the meaning of the story. As readers, we are constantly searching for symbols and interpreting them. As writers, we need to be thinking ahead and planning if we want to have rich symbolism throughout our work. A symbol is an object or concept that, below the surface, has another meaning; it signifies something else. But each and every one of you is already an expert on symbolism since we already studied symbolism in our poetry unit! I know that you guys already know this stuff! The last element that we are going to study in this unit is setting. Setting provides the time and place of the story. Setting answers the questions of where and when the story takes place. Setting may seem insignificant to a story, but ‘in good fiction, setting always functions as an integral part of the whole’ (Booth & Mays, 159).” Teaching Point (30-32 minutes): “Alright, so now we have done a formal overview of the elements in short stories. I would like you to go back now and read over what you have written about 20/20. Start on the next clean page of your journal and re-write your observations using the terms and ideas that we just talked about with short stories. Put your notes right alongside your journals and don’t be afraid to refer to them frequently! If you still have time after you have re-written your observations using the terms we just discussed, look back through your notes and see if there is anything that you neglected to discuss about 20/20. Can you pinpoint the climax in this story? What type of narrator do we have? Is Bill a dynamic or a static character? Write about everything that you can discover in this story!” Active Engagement (32-57 minutes): Students will work in their journals for about 20-25 minutes, re-writing and writing about 20/20. Teacher will walk around and read over students’ shoulders, offering advice or help. Closing (57-60 minutes): “Alright let’s pack it up for the day. You all did great work today with 20/20 and I look forward to working on more short stories with you! I enjoyed seeing the enthusiasm in your writing and in our discussion today! Read through The Jewelry once for homework; we will be working on that story tomorrow.” Formative Assessment: Teacher will go over the students’ journals to make sure they understand the concepts introduced in the day’s lecture. ????????IS THIS A READING OR WRITING DAY?????? Lesson Plan 2: Discussing and reacting to: “The Cask of Amontillado” Week 1: Thursday Materials: Students will have their anthologies, video projector for teacher’s copy, pens for annotating, whiteboard, markers, and student journals. Connection (0-2 minutes): “Good morning class! I hope you all enjoyed reading “The Cask of Amontillado” for homework last night. I know this story can be a little dark, but it is well-written and entertaining to read. Plus, it has a lot of great writing strategies for us to notice and apply to our own writing.” Active Engagement (2-20 minutes): “Alright, let’s go ahead and get into our literature circles for the day! You all know which circle you are in already for today so let’s start some useful discussion here.” Literature circles will have been established at the beginning of the week for students so they know what to do here. Each literature circle is made up of 5 different students. Groups are changed around every Monday. Students are to take notes as they read during homework and come to class prepared to discuss the reading in their small group and as a class. When students are in their groups, teacher will give further instructions. “Today, after you all discuss your own notes that you took, I want you to take a special look at the narrator. Who is the narrator? What type of narrator is speaking in ‘The Cask of Amontillado’?” As students confer in their small group, teacher will walk around the room and check in with each group. If students are having trouble staying on task or finding ideas for discussion, teacher will offer hints and/or provoking questions. Teaching Point/ Whole class discussion (20-40 minutes): “As I circulated the room, I noticed that you all brought up great points in your small groups. Let’s bring it back together as a whole class now and share some of these ideas! First of all, I would like to cover our main point of discussion for the day. What type of narrator do we have in ‘The Cask of Amontillado’?” This designed to be a discussion with meaningful interaction between students and teacher. Teacher will take notes on and annotate a copy of the short story on the video projector to model annotation for students. Following are examples of points that, ideally, students will bring up, and teacher will discuss if they do not: “So let’s start out with a look at the narrator of this story. As we can see already in the very first sentence, this is a first-person narrator. His name is Montresor and he is a character in the story, the main character to be precise. Is he a reliable narrator? Why or why not? He is an unreliable narrator. As you discovered, he ends up walling Fortunato into a hole in his basement and leaving him there. But why does he do that? The narrator gives us his rationale right away in the exposition: “The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as best I could, but when he ventured upon insult I vowed revenge” (Poe, 107). So naturally, we say to ourselves, ‘oh, Fortunato is a terrible person and he has done awful deeds!’ But we must not be quick to jump to wrong conclusions just because that is what our narrator is telling us. We don’t actually even know what Fortunato has ever done to Montresor. Perhaps he has murdered his puppies, but we don’t know that. Fortunato’s ‘injuries’ to Montresor could simply be glances the Montresor is misinterpreting. We, as readers, are hesitant to give him the benefit of the doubt when we discover that he lures another human being down to his basement and buries him alive. A sneaky little hook that Montresor uses in this piece is to address the reader directly: “You, who know so well the nature of my soul, will not suppose, however, that I gave utterance to a threat” (Poe, 107). What is the narrator doing here with the use of ‘you?’ He is attempting to build a rapport with the reader by addressing him or her directly. This pronoun is directed right at the reader, engaging them in the story and bringing them to his side. Montresor confides in the reader, begging them to side with him and see the story from his point of view. What else can we learn about the narrator from this story? We see that he is great at deceiving people because Fortunato had no idea that he was going to be walled up down in the vaults. Montresor managed to keeps his grievances and woes to himself, up until he kills Fortunato. We can see that when he says ‘it must be understood that neither by word nor deed had I given Fortunato cause to doubt my good will. I continued, as was my wont, to smile in his face, and he did not perceive that my smile now was at the thought of his immolation’ (Poe, 108). If Montresor is so good at deceiving Fortunato, what stops him from deceiving us as the readers? This is just further proof to us, as readers, that Montresor is unreliable and deceptive. Through this story, we also get a sense that Montresor is bitter. As the men descend into the basement, he alludes to once having been rich when addressing Fortunato: ‘you are rich, respected, admired, beloved; you are happy, as once I was’ (Poe, 109). He mentions here that Fortunato has all these traits and riches that he once had. Once can imagine Montresor saying this in his head with great bitterness and jealousy, while on the outside, he is all smiles and friendship with Fortunato. The text also tells us that Fortunato has servants and we can see the depth and size of the basement cavern that the two men enter because of how long it takes them to reach the pre-appointed place of the murder. Fortunato even remarks that ‘these vaults…are extensive’ (Poe, 11). This lifestyle by no means denotes poverty to us. If this is Montresor’s life while he is no longer ‘rich’, like Fortunato, what does this tell us about Fortunato’s current state of possessions, money, etc…? Through these textual inferences that Poe gives us, we can conclude that Fortunato was indeed a man of great fortune. Montresor also tells us that Fortunato was ‘a man to be respected and even feared’ (Poe, 108). Was this because of his riches and therefore his power? The narrator leaves us to infer conclusions about these indirectlystated ideas with the implications which are planted throughout the text.” Teacher will ensure that the text has been annotated and discussed for this information about the narrator. If there is still discussion time left over after a thorough discussion about the narrator, teacher will ask students to bring up other items that they noticed and took notes on during their reading of the text. Students can also discuss ideas that came up within their small-group discussions at the beginning of class. Active Engagement (40-58 minutes): “Alright let’s switch gears now. Go ahead and pull out your journals and we are going to do some journaling on ‘The Cask of Amontillado.’ React, as a writer, to the discussion we just had. Go ahead and use your notes. Why does Poe use Montresor as the narrator in this story? How is making Montresor the narrator more effective to this story than a different type of narrator, such as an omniscient one? What devices and ways of writing do you see in this story that you may use in your own short story? Think about these questions and react to this short story as the great writers that you all are!” Students will write for about 20 minutes in their journals. Teacher will circulate the classroom to help students that are struggling or have questions. Closing (58-60 minutes): “Ok, we are going to pack it up for the day. We had a great discussion today on this short story and I look forward to reading your journal responses to see what you all, as writers, took away from Edgar Allan Poe’s writing. I am gearing you guys towards writing your own short stories so I want you to always be focusing on reading as a writer, not just a reader! Great work today.” Formative Assessment: Teacher will look over students’ journals to make sure that they are reading and responding as writers, and thinking ahead to how they could incorporate ideas that they are seeing in mentor texts to their own writing. If students are struggling to make the leap from reading as readers to reading as writers, teacher will ask to see them one-on-one after class to make sure they stay kept up with the rest of the class. Lesson Plan 3: Demonstrating the Writing Process Week 2: Monday Materials: Students’ journals, pens, overhead video projector Connection (0-2 minutes): “Good morning class! Last weekend we finished class working on how to incorporate