The Grotesque in Theory

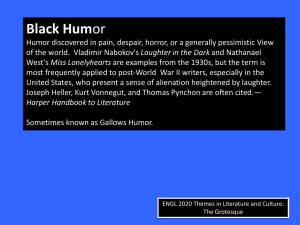

advertisement

English 2020-24 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Spring 2015 100-225 | PH 308 The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque The true iconoclast is the image itself which explodes . . . allegorical meanings, releasing new insights. Thus the most distressing images in dreams and fantasies, those we shy away from for their disgusting distortion and perversion, are precisely the ones that break the allegorical frame of what we know about this person or that, this trait of ourselves or that. The “worst” images are the best, for they are the ones that restore a figure to its pristine, numinous, power. . . . James Hillman, Re-Visioning Psychology The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque There is a nature that is grotesque within The boulevards of the generals. Why should We say that it is man’s interior world Or seeing the spent, unconscious shapes of night, Pretend they are shapes of another consciousness? The grotesque is not a visitation. It is Not apparition but appearance, part Of that simplified geography, in which The sun comes up like news from Africa. Wallace Stevens, “A Word with Jose Rodriguez-Feo” The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Philip Thomson, The Grotesque A DEFINITION The preceding discussion of the role of the abnormal in the grotesque should not be allowed to dominate our notion of the phenomenon as a whole. The abnormal is a secondary factor, of great importance but subsidiary to what I have outlined as the basic definition of the grotesque: the unresolved clash of incompatibles in work and response. It is significant that this clash is paralleled by the ambivalent nature of the abnormal as present in the grotesque: we might consider a secondary definition of the grotesque to be 'the ambivalently abnormal'. The Grotesque by Philip Thomson ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque The Grotesque in Theory As William J. Free reminds us, the grotesque is multifaceted. In a discussion of the grotesque in Fellini’s I Clowns (1972), Free argues that the grotesque’s “fanciful and sinister” nature actually has two distinct faces, perhaps best represented visually in the paintings of Pieter Brueghel and Hieronymous Bosch. Free, William J. “Fellini’s I Clowns and the Grotesque.” Federico Fellini: Essays in Criticism. Ed. Peter Bondanella. NY: Oxford UP, 1978: 188-201. The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque For Free, Brueghel’s art exemplifies an essentially comic “irreverent attitude toward his subject” and conveys “the artist’s joy at contemplating the hurly-burly confusion of life which swallows up any attempt of history to impose meaning on it” . . . The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque The Peasant Dance The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque . . . which Bosch’s “terrifying grotesque,” on the other hand, exhibits an “insanely demonic world peeping from beneath the order of life and threatening to destroy it in disgusting violence” (Free 191). The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque The Grotesque in Theory Christ Carrying the Cross ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque According to Wolfgang Kayser in The Grotesque in Art and Literature, the grotesque is The expression of the estranged or alienated world . . . . [it] is a game with the absurd, the sense that the grotesque artist plays, half laughingly, half horrified, with the deep absurdities of existence. The grotesque is an attempt to control and exorcise the demonic elements of the world. (185). The “unity of perspective” attained by all grotesque art thus has its source, as Kayser would insists, in the belief that “the divinity of poets and the shaping force of nature have altogether ceased to exist” (186). The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Mary Cass Canfield declares that the grotesque testifies that “The artist is ill. Life is too literal and he takes to his fancy. Life is too pervasively discordant and so his fancy does not soar, does not sanely and safely create beautiful rhythms, but becomes infected with unrest, turns ape to the actual, is rebellious slave to what it would be free from” and claims that all “grotesques are damned” (9-10; my emphasis); Canfield’s diction is itself a revelation: the grotesque prevents the artist form “soaring” (presumably above the earth, as Guido, seeking to escape his earthly fate, erroneously tried to do in 8 1/2’s famous opening scene) condemning him to the mimicking or “aping” of the actual, from which Canfield’s Northern (and Platonic) mind-set feels he should be free. Canfield’s ascensionism is, however, strangely correct. The grotesque is, as she insists, a revelation of immanence; it is stamped “on the observe of the medal of idealism” (3). The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque In the bed the writer had a dream that was not a dream. As he grew somewhat sleepy but was still conscious, figures began to appear before his eyes. He imagined the young indescribable thing within himself was driving a long procession of figures before his eyes. You see the interest in all this lies in the figures that went before the eyes of the writer. They were all grotesques. All of the men and women the writer had ever known had become grotesques. The grotesques were not all horrible. Some were amusing, some almost beautiful, and one, a woman all drawn out of shape, hurt the old man by her grotesqueness. When she passed he made a noise like a small dog whimpering. Had you come into the room you might have supposed the old man had unpleasant dreams or perhaps indigestion. For the procession of grotesques passed before the eyes of the old man, and then, although it was a painful things to do, he crept out of bed and began to write. Some one of the grotesques had made a deep impression on his mind and he wanted to describe it. The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque At his desk the writer worked for an hour. In the end he wrote a book which he called "The Book of the Grotesque." It was never published, but I saw it once and it made an indelible impression on my mind. The book had one central thought that is very strange and has always remained with me. By remembering it I have been able to understand many people and things that I was never able to understand before, The thought was involved but a simple statement of it would be something like this: That in the beginning when the world was young there were a great many thoughts but no such thing as a truth. Man made the truths himself and each truth was a composite of a great many vague thoughts. All about in the world were the truths and they were all beautiful. The old man had listed hundreds of the truths in his book. I will not try to tell you all of them. There was the truth of virginity and the truth of passion, the truth of wealth and of poverty, of thrift and of profligacy, of carelessness and abandon. Hundreds and hundreds were the truths and they were all beautiful. The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque The old man had listed hundreds of the truths in his book. I will not try to tell you all of them. There was the truth of virginity and the truth of passion, the truth of wealth and of poverty, of thrift and of profligacy, of carelessness and abandon. Hundreds and hundreds were the truths and they were all beautiful. And then the people came along. Each as he appeared snatched up one of the truths and some who were strong snatched up a dozen of them. It was the truths that made the people grotesques. The old man had quite an elaborate theory concerning the matter. It was his notion that the moment one of the people took one of the truths to himself, called it his truth, and tried to live his life by it, he became a grotesque and the truth he embraced became a falsehood. The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque You can see for yourself how the old man, who had spent all of his life writing and was filled with words, would write hundreds of pages concerning this matter. The subject would become so big in his mind that he himself would be in danger of becoming a grotesque. He didn't, I suppose, for the same reason that he never published the book. It was the young thing inside him that saved the old man. Concerning the old carpenter who fixed the bed for the writer, I only mentioned him because he, like many of what are called very common people, became the nearest thing to what is understandable and lovable of all the grotesques in the writer's book. The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque François Rabelais (1494-1553). French priest and author The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque François Rabelais The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque François Rabelais The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque François Rabelais The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Gustave Doré (1832-1883). French illustrator The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Gustave Doré’s Rabelais Illustrations The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Gustave Doré’s Rabelais Illustrations The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Gustave Doré’s Rabelais Illustrations The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Gustave Doré’s Rabelais Illustrations The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, Mister Rogers, and Me Sunday, March 25, 2007 Mister Rogers Seeing an image of the late Fred Rogers (1928-2003) on the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences website reminded me that I have meant to record here my two encounters with this gentle, wonderful man. The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, Mister Rogers, and Me Mister Rogers I was on a plane flight in the early eighties from Atlanta to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and was surprised to find Fred Rogers sitting across the aisle from me, but it was not the first time our paths had crossed. The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, Mister Rogers, and Me A decade before I was standing in a bookstore in downtown Pittsburgh (I grew up in Oil City, PA, about fifty miles north of the Steel City), drooling at the most comprehensive collection of books I had ever seen at the time, when behind me I heard an unmistakable voice asking the information desk if the store had "Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel." As luck would have it, I was standing in front of the medieval literature section, and I pulled the book off the shelf and handed it to Mister Rogers. The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, Mister Rogers, and Me Years later, the sketch in Kentucky Fried Movie--at least I think that was the movie (1977)--in which the host of a children's television show pleads with the kids at home to get their parents out of the room so he can read them another chapter of Lady Chatterley's Lover made me remember the moment. Mister Rogers, of course, would never have actually read to visitors to his neighborhood the profane, grotesque masterpiece (written by a French priest) which I handed him that day many years ago. But it says everything about him that he had sought it out as his own essential reading. He was a man of great depth and humanity with the profound gift of seeming profoundly simple and transcendentally kind. Only a deranged academic like Willow's mom would think otherwise. The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel Ribald and Bawdy Erudite Picaresque Folkloric Humanist Grotesque The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Wherever men laugh and curse, particularly in a familiar environment, their speech is filled with bodily images. The body copulates, defecates, overeats, and men's speech is flooded with genitals, bellies, defecations, urine, disease, noses, mouths, and dismembered parts. Even when the flood is contained by norms of speech, there is still an eruption of these images into literature, especially if the literature is gay or abusive in character. . . . This boundless ocean of grotesque bodily imagery within time and space extends to all languages, all literatures, and the entire system of gesticulation; in the midst of it the bodily canon of art, belles lettres, and polite conversations of modern times is a tiny island. This limited canon never prevailed in antique literature. In the official literature of European peoples it has existed only for the last four hundred years. . . --Mikhail Bakhtin The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque In Rabelais and His World, Bakhtin shows that in the past four hundred years a preoccupation with politeness, taste, manners, and rational, institutional values has eclipsed an earlier, pre-modern fascination with the "grotesque body," imposing a "bodily canon" on expression and on perception itself. This earlier wonder at the "earthy"—created and sustained by folkloric imagination—is readily apparent, according to Bakhtin, as the shaping force behind the exuberant but thoroughly grotesque genius of the French priest.* The "grotesque" body depicted in pre-Renaissance art in general and Gargantua and Pantagruel in particular is one which, according to Bakhtin, unashamedly "fecundates and is fecundated, that gives birth and is born, devours and is devoured, drinks, defecates, is sick and dying.“ The "bodily canon," however, asserts instead that human beings exist outside the hierarchy of the cosmos. It stresses The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque that we are finished products, defined characters, and in its reductionism attempts to seal off the bodily processes of organic life from any interchange with the external world. The bodily canon therefore seeks to: 1) close all orifices; 2) stop all mergers of the body with the external world; 3) hide all signs of inner life processes and bodily functions (hence, for example, prohibitions against farting or belching in public); 4) ignore all evidence of fecundation and pregnancy; 5) eliminate protrusions; 6) present an image of a completed, rational, individual body. As a flight from the reality of human embodiment, the anality described by culture critics from Sigmund Freud to Ernest Becker and Norman O. Brown (who argued for the essential anality of capitalism's pursuit of "filthy lucre") is thus thoroughly modern, both cause and effect of the bodily canon. The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Rabelaisian man, if Bakhtin's thesis is correct, possessed "true . . . fearlessness" in the face of the human condition. Because he felt his own body to contain within it the presence of the cosmos, because he experienced his embodiment as "a point of transition in a life eternally renewed, the inexhaustible vessel of death and conception," Rabelaisian man found himself at home in the world in a way that modern man finds difficult to imagine. Before the censure of the bodily canon, Bakhtin insists, even urine and dung could appear to be "gay matter, which degrades and relieves at the same time, transforming fear into laughter" and not as memento mori. ("In the modern image of the individual body," Bakhtin reminds, "sexual life, eating, drinking, and defecation have radically changed their meaning: they have been transferred to the private and psychological level where their connotation becomes narrow and specific, torn away from the direct relation to the life of society and to the cosmic whole. In this new connotation they can no longer carry on their former philosophic functions.") The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. Repression of the bodily—the achievement of centuries—is now efficiently accomplished in a single childhood. All parents, myself included, pass on the bodily canon to our progeny. It's the least we can do. Children have in the space of a few years to attain the advanced level of shame and revulsion that has developed over many centuries. Their instinctual life must be rapidly subjected to the strict control and specific molding that give our societies their stamp, and which The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque developed very slowly over centuries. In this the parents are only the (often inadequate) instruments, the primary agents of conditioning; through them and thousands of other instruments it is always society as a whole, the entire figuration of human beings, that exerts its pressure on the new generation, bending them more or less perfectly to its purpose. The Grotesque in Theory: Mikhail Bakhtin ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque In Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Marco Polo regales Kublai Khan with the story—one of five in the book designated as tales of “Cities & the Sky”—of Perinthia, a metropolis which, from its very inception, had been intended as a utopia, its ordering cosmologically inspired. In Perinthia, we learn, all aspects of the city are laid out according to the highest wisdom of astrology and astronomy. Buildings, for example, are cited in such a way as to receive “the proper influence of the favoring constellations. The astronomers who oversaw Perinthia’s development from the ground up guaranteed the city that it would, without question, “reflect the harmony of the firmament.” Reality, of course, turns out to be anything but ideal. For, Marco Polo informs us, The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque In Perinthia’s streets and squares today you encounter cripples, dwarfs, hunchbacks, obese men, bearded women. But the worse cannot be seen: guttural howls are heard from cellars and lofts, where families hide children with three heads or six legs. (144) Such grotesques bring the astronomer/architects of Perinthea to an intellectual impasse, one that crops up all through Calvino’s splendid fictions/thought experiments: Either they must admit that all their calculations were wrong and their figures are unable to describe the heavens, or else they must reveal that the order of the gods is reflected exactly in the city of monsters. (145) The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque For the grotesque at its best the second alternative seems the only viable one. It celebrates the revelation that “the order of gods is reflected exactly in the city of monsters.” It brings us “news from Africa.” The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Bibliography Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1984. Bazin, André. “Cabiria: The Voyage to the End of Neo-Realism.” What is Cinema? Vol. II. Ed. and Trans. Hugh Gray. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971: 83-92.. Calvino, Italo. Invisible Cities. Trans. William Weaver. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1972. Canfield, Mary Cass. Grotesques and Other Reflections on Art and the Theatre. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1972. The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Bibliography Cox, Harvey. “The Purpose of the Grotesque in Fellini’s Films.” Celluloid and Symbols. Ed. John C. Cooper and Carl Skrade. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1970: 92-101. Fiedler, Leslie. Freaks: Myths and Images of the Secret Self. NY: Simon and Schuster, 1978. Free, William J. “Fellini’s I Clowns and the Grotesque.” Federico Fellini: Essays in Criticism. Ed. Peter Bondanella. NY: Oxford UP, 1978: 188-201. Hillman, James. “Psychology: Monotheistic or Polytheistic.” In The New Polytheism. Ed. David L. Miller. Dallas: Spring Publications, 1981: 109-42. ___. Revisioning Psychology. NY: Harper and Row, 1975. The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque Bibliography ___, with Laura Pozzo. Inter Views. NY: Harper and Row, 1983. Kayser, Wolfgang. The Grotesque in Art and Literature. Bloomington: Indiana U P, 1963. Stevens, Wallace. The Collected Poems. NY: Knopf, 1954. Thomson, Philip. The Grotesque. Critical Idiom Series. London: Methuen, 1972. The Grotesque in Theory ENGL 2020 Themes in Literature and Culture: The Grotesque