Measuring Efficiency in the Presence of Head-to

advertisement

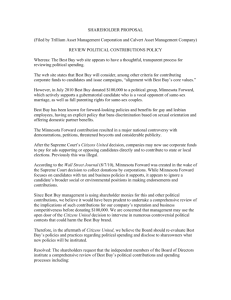

Measuring Efficiency in the Presence of Head-to-Head Competition Thomas R. Sexton, Ph.D., College of Business, Stony Brook University Herbert F. Lewis, Ph.D., Department of Technology and Society, Stony Brook University Background Political campaign finance reform has received much attention in recent years. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (McCain-Feingold Act) placed new limits on who can contribute, and how much they can contribute, to political campaigns. Campaign managers must pay greater attention to the efficiency with which campaign funds are spent. 2 The Traditional DEA Model The traditional Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model, which measures the relative efficiency of operational units that consume multiple inputs to produce multiple outputs, is not well suited for this challenge. Fails to incorporate the head-to-head nature of political campaigns in which a candidate spends money not only to increase the number of votes he or she receives but also to reduce the number of votes that his or her opponents receive. 3 Head-to-Head Competition Head-to-head competition is common in sports. ◦ Zak et al. (1979), Mazur (1994), Anderson and Sharp (1997), Sueyoshi et al. (1999), Lozano et al. (2002), Haas (2003), Fried et al. (2004), and Cooper et al. (in press). ◦ However, none of these explicitly incorporates the head-to-head nature of individual contests. ◦ Sexton and Lewis (2003), and Lewis and Sexton (2004a, 2004b) apply DEA to baseball and formulate models in which a team uses its resources both to score runs and to inhibit their opponents from doing the same. ◦ However, their models analyze season-long data rather than individual contests. 4 Our Paper: Political Campaigns We present a new DEA model that explicitly incorporates the head-to-head nature of political campaigns. We apply the model to the U.S. Congressional races in New York State in 2002, 2004, and 2006. ◦ We identify races in which the loser would have won had he or she been efficient. ◦ We identify incumbents as being particularly wasteful in their campaign spending. ◦ We explore how campaign efficiency and the aggregate amount of wasteful spending have evolved over this period. 5 Earlier Studies Earlier studies have addressed the topic of whether spending by an incumbent or a challenger is more efficient. ◦ Jacobson (1978) and Abramowitz (1988) claim that spending by a challenger is more efficient and produces larger gains than does spending by an incumbent. ◦ Others argue that campaign spending by incumbents and challengers are both efficient while still others think that neither incumbent spending nor challenger spending is efficient (Levitt 1994, Gerber 1998, and Erikson and Palfrey 2000). See also Palda (1996), Gerber (2004), Mangee (2002), Palda (2002), Goodliffe (2004), and Primo (2004). 6 DEA Methodology Linear programming-based methodology first introduced by Charnes, Cooper, and Rhodes (1978). DEA is an extreme point method that compares each producer with only the “best” producers. It has been applied in many fields: criminal justice (Lewin et al. 1982), electricity production (Fare and Primont 1984 and Norton et al. 2002), public financing for school bus transportation (Sexton et al. 1994), retail store management (Anderson 1996), campaign financing (Coates 1999), and blood centers (Pitocco and Sexton 2005). 7 The DEA Approach Collection of DMUs, each of which consumes multiple inputs to produce multiple outputs. Allows for site characteristics: factors that affect efficiency but lie beyond control of the DMU. Establishes the efficient frontier based on the observed best performance among all DMUs. Evaluates the efficiency of each DMU relative to this frontier. The best producers lie on the efficient frontier and can be used as a reference set for the inefficient DMUs that do not lie on the frontier. 8 Campaign DEA Model Consider an election in which there are nt candidates competing in period t. ◦ We exclude candidates who are unopposed, those who spend less than $5000, and those who receive no votes in the general election. Let xjt = money spent by Candidate j and x'jt = total money spent by all of Candidate j’s opponents combined. Let yjt = number of votes cast for Candidate j and let y'jt = total number of votes cast for all of Candidate j’s opponents combined. 9 One Candidate xjt Candidate j yjt x'jt Candidate j’s Opponent(s) y'jt 10 Standardized Spending and Votes Candidate j Candidate j’s Opponent(s) 11 Candidate Status Define three binary variables: ◦ Let Ijt = 1 if Candidate j is an incumbent, with Ijt = 0 otherwise. ◦ Let Cjt = 1 if Candidate j is a challenger, with Cjt = 0 otherwise. ◦ Let Sjt = 1 if Candidate j is running for an open seat, with Sjt = 0 otherwise. We consider candidate status to be a site characteristic. 12 Maximize target’s vote differential subject to Target spends less money Target’s opponents spend more Target gets more votes Target’s opponents get fewer votes Variable returns to scales Target has same status Nonnegativity 13 Target Spending and Votes 14 Three Efficiency Measures : Own spending : Own votes : Opponents’ votes 15 Candidate's Votes Received Thousands If All xj Were Equal . . . 1000 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 Candidate A 100 0 0 200 400 600 800 1000 Thousands Opponents' Votes Received 16 Candidate's Votes Received Thousands If All xj Were Equal . . . 1000 900 800 Candidate B 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 0 200 400 600 800 1000 Thousands Opponents' Votes Received 17 Candidate's Votes Received Thousands If All xj Were Equal . . . 1000 900 800 700 600 500 400 Candidate C 300 200 100 0 0 200 400 600 800 1000 Thousands Opponents' Votes Received 18 Data We obtained data on votes received and on campaign spending from the Federal Election Commission web site (http://www.fec.gov/). We chose to analyze the congressional districts in New York State because they are designed to each incorporate, as closely as possible, precisely the same population. In addition, New York has a large number of congressional districts (29) and candidates, which is desirable in any DEA model. 19 Candidates and Races Two-Way ThreeYear Candidates Races Way Races 2002 40 17 2 2004 46 20 2 2006 32 16 0 All 118 53 4 20 Efficient Candidates Efficiency Measure Year Candidates * 2002 40 2004 46 2006 32 All 118 Own Spending 23 (57.5%) 31 (67.4%) 25 (78.1%) 79 (66.9%) P-value = 0.0808 in a chi-square test. Opponents’ Own Votes Votes* 18 (45.0%) 23 (50.0%) 17 (53.1%) 58 (49.2%) 10 (25.0%) 19 (41.3%) 16 (50.0%) 45 (38.1%) 21 The Consequences of Inefficiency In 6 of the 57 races (10.5%), a losing candidate would have won had he or she been efficient. In each case, the losing candidate’s target candidate would have been a winner, would have spent less money than the losing candidate, and would have faced an opponent who spent more than the losing candidate’s opponent did. One of the six was a challenger, two were incumbents, and three were running for an open seat. 22 Election Outcome Reversals Actual Spending Votes If Loser Efficient Spending Votes 1.000 $958,545 80,886 $958,545 49,408 1.000 0.611 $1,399,768 78,465 $739,234 78,465 1.000 1.000 1.000 $1,908,440 156,354 $1,923,967 153,723 Manger (C) 1.000 1.332 0.983 $1,367,904 121,855 $1,367,904 162,280 Higgins (O) 1.000 1.000 1.000 $1,332,162 143,332 $1,332,162 118,792 Naples (O) 0.761 1.000 0.829 $1,581,433 139,558 $1,204,117 139,558 Hall (C) 1.000 1.000 1.000 $1,602,865 100,119 $1,602,865 67,445 Kelly (I) 0.920 1.318 0.674 $2,519,164 95,359 Arcuri (O) 1.000 1.000 1.000 $2,192,558 109,686 $2,192,558 82,485 Meier (O) 1.000 1.021 0.752 $1,586,397 91,504 Kuhl (I) 1.000 1.000 1.000 $1,475,375 106,077 $2,351,018 98,845 Massa (C) 1.000 1.017 0.932 $1,445,525 100,044 $1,445,525 101,725 Year CD Candidate 2002 2004 2004 1 1 27 2006 19 2006 24 2006 29 EX θy Ey’ Bishop (O) 1.000 1.000 Grucci (O) 0.528 Bishop (I) $2,316,985 125,678 $1,586,397 93,397 23 Savings and Vote Increases Total Spending Year * Total Votes Candidates Actual If All Efficient % Reduction* Actual If All Efficient % Increase 2002 40 $20,316,640 $9,546,383 53.0% 2,722,205 3,335,012 22.5% 2004 46 $32,501,954 $23,742,105 27.0% 5,002,315 5,877,840 17.5% 2006 32 $40,392,018 $35,687,382 11.6% 2,799,557 3,119,584 11.4% All 118 $93,210,612 $68,975,870 26.0% 10,524,077 12,332,437 17.2% P-value = 0.0366 in Kruskal-Wallis one-way nonparametric ANOVA. 24 Spending and Votes per Candidate Year Spending per Candidate If All Actual Efficient Votes Received per Candidate If All Actual Efficient 2002 $507,916 $238,660 68,055 83,375 2004 $706,564 $516,133 108,746 127,779 2006 $1,262,251 $1,115,231 87,486 97,487 All $789,920 $584,541 89,187 104,512 25 Spending per Vote Received Spending per Vote Received Year * Actual If All % Efficient Reduction* 2002 $7.46 $2.86 61.7% 2004 $6.50 $4.04 37.8% 2006 $14.43 $11.44 20.7% All $8.86 $5.59 36.9% P-Value = 0.0157 in Kruskal-Wallis one-way nonparametric ANOVA. 26 Incumbents Much Less Likely to be Efficient Spenders Ex = 1 Ex < 1 Total % Ex = 1* Incumbents 15 37 52 28.8% Challengers 55 0 55 100.0% Open Seat 9 2 11 81.8% All 79 39 118 66.9% * P-value < 0.00005 in a chi-square test. 27 Conclusions About two-thirds of Congressional candidates in NYS in 2002, 2004, and 2006 spent campaign funds efficiently. However, about half could have received more votes and more than 60% could have kept more votes away from their opponents. Campaigns spend more, but more efficiently. ◦ Campaign spending per candidate and spending per vote roughly doubled from 2002 to 2006. ◦ Inefficiency accounted for more than half of campaign funding in 2002 but only about 10% in 2006. 28 Conclusions More than 10% of losing candidates would have won had they been efficient. Effect of inefficiency is dominated by incumbency status. ◦ Challengers and candidates running for an open seat are much more likely to be efficient in their spending. ◦ Yet incumbents won over 96% of elections. ◦ One possible explanation is that incumbents are likely to have more money on hand. ◦ Given the limited uses for campaign funds, incumbents have little choice but to spend the money on campaign activities. 29