Accounting for the Differences among the Witnesses: A Disciplined

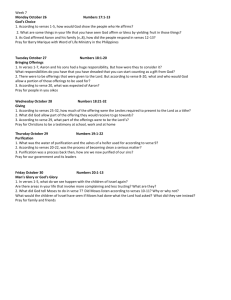

advertisement

Textual Criticism and Its Application: Recollecting the Experience in Editing SN I for PTS G.A. Somaratne Co-Director – Dhammachai Tiptaka Project 1 This Presentation • I edited the SN I for PTS in the years 1994 and 1995 at Oxford. • How did I account for the differences among the witnesses in my effort to retrace the steps of the ancient scribes in recovering the text of SN I at least several steps closer to the original? – G.A. Somaratne, The Saṃyuttanikāya of the Suttapiṭaka, Volume I: The Sagāthavagga, PTS: Oxford, 1998. 2 What is Textual criticism? • a scientific method of restoring the original text. • a disciplined and a creative process. • Its “rules” tell how the textual critic applies the common sense with good judgment and insight, to a group of corruptions accrued in the given text through its successive transcription over a period of time. 3 What is a Text? What is a Manuscript? • Text is the intangible content or the wording of a given text. • Text can be copied. • The copy so produced perishes but the text survives, if it has been copied again. • A particular copy of the text so produced is a manuscript. • The same text may be written down in many different manuscripts. 4 No copy of an ancient text is perfect. Why? • “A text is a traveler who goes from one inn to another, losing an article of luggage at each halt”. • When producing a new copy, the scribe naturally adds errors to the text. • Copying is a source of both survival and corruption. • The very process that preserves the text, that is, copying, also exposes it to danger. • When writing is done on perishable materials, the survival of a text over a long period of time is possible, only if it is copied many times. • Such a text is especially liable to corruption. 5 Witnesses to the Text • The surviving copies are the witnesses to the text. • They bear witness in determining the text’s hypothetical original form. • The copies deviate from the hypothetical earlier text. • In recovering the original form of the words, the textual critic should account for the differences among the witnesses. • He should retrace the steps of the ancient scribes. 6 Collation • Collation is the assembly of data into a standard order. • The critic collates the copies in order to draw conclusions about the divergences in them. • The goal of collation is to recover an earlier, more authentic, and therefore superior, form of the text. • Such restoration is known as a critical recension. 7 Recencio & Emendacio • Two main processes of the method: • (1) Recension (recencio): – the process to select the most trustworthy evidence (manuscripts) on which to base the text that which stands nearest to the original. – This selection is only possible after a thorough examination of all the available evidence. • (2) Emendation (emendacio): – the process to eliminate errors that are found even in the best manuscripts. – It is a deliberate but systematic attempt to overrule the manuscript evidence. 8 Structure of the Text and Sutta Titles • The uddānagāthās provide a structure to a text. • The Sutta titles and section titles are given in the uddānagāthā. • These verses are often metrically corrupt or they are poorly composed to fit every name of the vagga in the order of their appearance into one verse. • I followed Be supported by uddānagāthā when giving titles to the suttas. • The title of the sutta 3 of the Kosalasaṃyutta: jarāmaraṇa goes against the uddānagāthā that reads rājā, apparently a corruption due to metathesis of jarā. • In the Mārasaṃyutta sutta 2 title hatthirājavaṇṇa goes against the uddānagāthāta’s nāgo. 9 Suttas and Vaggas • SN I contains 271 suttas divided into 28 vaggas. • Uddānagāthās of 8 vaggas have no vagga fixing word like dasamo, vaggo, dasa, pañcakaṃ, dvādasa, cuddassa. I call them open vaggas, not closed. • The order of appearance of each sutta is fixed in the uddānagāthā as each name occurs. • In two places navamaṃ and navamo are read in the uddānagāthā further fixing the order. • Four vaggas have 5 Suttas each, 3 vaggas have 12 Suttas each, and one vagga comes with 14, and another with 11. • The rest, 19 Vaggas, contain 10 Suttas each, which is normally the standard number of suttas for a vagga. 10 Manuscripts • The witnesses to our text were: – the palm leaf manuscripts of SN in the scripts of Sinhala, Burmese, and Lanna – some existing editions and the variants recorded in them. • In this purification process, six manuscripts of the text were used. • Readings of these witnesses were recorded manually by writing down all variants against the base text (Feer’s edition), one by one. (= collation) • Léon Feer, The Saṃyutta-nikāya of the Sutta-piṭaka, Volume I, PTS: London, 1984. • This helped identify the corruptions, mistakes and intentional deviations accumulated in the transmitted text over the period of its transmission. 11 S4: Sinhalese – India Office • Two Sinhalese: S4. S5. (S2, that Feer had used only half was read for the other half). • S4 : The India Office Library of the British Library, London: Or. 6599 (40) – 454 ola-leaves (each leave cm.5.8 x cm.60.5) with 10 lines per page; page numbering: both 1,2,3,4 etc and ka-kaḥ (16 folios), kha-khaḥ etc; Sagāthavagga constitutes the first 58 leaves, from ka to gḷ – Buddhist era 2434 (A.D. 1890/1); Dambaliyadde Rājaguru Mudiyanselāge Ukkurāla Näkätrāla – namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammāsambuddhassa. evam me sutaṃ. ekaṃ samayaṃ bhagavā (the first sutta) …. saccasaṃyuttaṃ samattaṃ … (more personal things continue) 12 S5: Sinhalese - Colombo • The Colombo National Archives? The Colombo Museum Library? – A microfilm copy of the Sagāthavagga portion, JOB NO 93/148. 3/3/2/172/93. SAṂYUTTA NIKĀYA. MF-P; not Colombo Museum Library no. 70 (D.2); could be 71(A.R.I). – Numbering: ka-kaḥ, kha-khaḥ etc; 8 lines per page. Sagāthavagga = pages ka to cā – Date & Scribe: unknown (beautifully written) – namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammāsambuddhassa. evam me sutaṃ (the first sutta). …. – ekādasasaṃyuttaṃ samattaṃ. sagāthavaggo. devatā devaputto … vāsavo ti. evam me sutaṃ ekaṃ samayaṃ …. saḷāyatanapaccayā phasso phassapaccayā. 13 B2: Burmese – India Office • two Burmese: B2. B3 • B2: The India Office Library of the British Library; Phayre Collection 10; catalogue number: IOL I.O.PALI 10 – The first three Vaggas of the Saṃyuttanikāya; 264 ola-leaves; Numbering: ka to tāḥ – Sakarāj 1203 (= A.D. 1841) – More details: JPTS Vol. 1 (1882) 14 B3: India Office • The India Office Library of the British Library; catalogue number: IOL I.O.MAN.PALI 100 – ka-kaḥ (12 leaves), kha-khaḥ etc.; 244 ola-leaves from ka to pī; 9 lines per page; a folio cm 6.5x49. gold plated. – Contains two separate sections: sagāthavagga: namo tassa bhagavato … evaṃ me sutaṃ (first sutta) … sagāthavaggo paṭhamo. (some writing in Burmese). – nidānavagga: namo tassa bhagavato … evaṃ me sutaṃ (first sutta of the vagga) … nidānavaggasaṃyuttaṃ samattaṃ. Some writings in Burmese (2 leaves). 15 L1: Northern Thai • two Northern Thai (Lanna): L1. L2. • A Northern Thai manuscript of the Commentary (C3) • L1: A photo-copy supplied by Prof. Oskar von Hinuber; film number: 04-017-00. – ka-kaḥ (12 leaves), kha-khaḥ etc; 5 lines per page; 5.0x56.5cm; ka—tho – A.D. 1549 by Javanapañña – subhamatthu svasḍī jayas tu antarāyaṃ. namo tassa bhagavato … evam me sutaṃ (the first sutta) … sagāthavaggo ekādasa saṃyutto samatto pariniṭṭhito. pāṭhasagāthāvaggavaṇṇanā niṭṭhitā. 16 L2: Northern Thai • Microfilm number: 100.00. title no. 7 of film no. 14 of Vat Lai Hin microfilms. Contents: no. 95-101.8. (accompanies a commentary) – ka-kaḥ (12 leaves), kha-khaḥ etc; ka to ḍā (follios ga to jaḥ are missing). – A.D. 1543 – First part (ka to khaḥ): sakkatvā buddharatanaṃ sakkatvā dhammaratanaṃ sakkatvā saṅgharatanaṃ. namo tassa bhagavato … evam me sutaṃ (first sutta) … kismiṃ loko samuppanno kismiṃ ku. – Second part: ti idaṃ hi na jāyati na jiyyati …. sakko devānamindo sudhammāya sabhāyaṃ deve tāvatiṃse a. C3 • In the same microfilm of L2 – Spk I 31—89 (PTS); Spk I 122—315 (PTS). – The rest of the text is missing. 17 Printed Editions • Four editions of the text and the PTS commentary were used throughout: • R = Léon Feer’s PTS Edition (1884) & the variants recorded in it: B1 (Paris), S1 (Copenhagen), S2 (British Musem), S3 (Dr. Morris); • Se = Sinhalese Buddha Jayanti Tipiṭaka Granthamālā edition (1960), and its two manuscripts: Ss1 (Pälmaḍulla) and Ss2 (Galle); • Sa = Sinhalese edition by Bandaramulle Amarasiha Thera (1926) of Alutgama. This was used only up to the end of Kosalasaṃyutta as its readings agreed with our Se and S4 and S5; 18 • Be = Burmese Chaṭṭhasaṅgāyanā edition (1957). This edition is based on: Sī = sīhaḷapotthake, Syā = syāmapotthake, Kaṃ = kambojapotthake, I = iṅgalisapotthake, Ka = katthaci marammapotthake, Ṭha = aṭṭhakathā; ? = siyā nu kho porāṇapāṭho ti takkitapāṭho; • Te = King Rāma V Memorial Thai Edition (1926—28). On the title page we read: ahiṃsakattherena medhādhammarasena ādo sodhito Tissadhammattherena dhammapiṭakena puna sodhito rājappamukhena syāmaraṭṭhavāsinā mahājanena muddāpito. • C1 = The PTS commentary, Sāratthappakāsinī Saṃyuttanikāya-aṭṭhakathā, edited by F.L. Woodward (1929), and its variant recorded from C2 Thai (Khmer) manuscript (Paris). 19 Abbreviations • For convenience and to reduce the bulkiness of footnotes, some abbreviations as shown below were adopted: • L = L1.L2; S = Se.S1.S2.S3.S5; B = Be.B1.B2.B3. More examples: • S1-5 = S1.S2.S3.S5; S15 = S1.S5; S12 = S1.S2; S1-3 = S1.S2.S3; S13-5 = S1.S3.S4.S5; B13 = B1.B3; B23 = B2.B3; C13 = C1.C3; C1-3 = C1.C2.C3 20 Corruptions in the Text • We edit a text because we believe that there are errors. • If you can imagine an error, a scribe has probably made it. • Some likely errors that scribes add to the text have been classified into: – visual and psychological, – accidental and deliberately made, – involuntary, semi-voluntary and voluntary, etc. • I will highlight a few that I came across in the SN I. 21 Careless Reading and Careless Writing • A group of errors generated through either careless reading of the exemplar or careless transcribing of letters. • Letters which resemble one another are often subjected to this error. • In our text, the confusions between va and ca, yo and so (p.183), manāpapariyantiṃ and manappariyantiṃ (p.183), uppanno and upapanno (p.208), pahāta- and bahūta- (p.212), and sahassaṃ > saṃgassaṃ (S1.S3.S4) (v.708) belong to this category. • Such confusions could also occur when the exemplar manuscript is in an unfamiliar writing. • For example, nhā- of nhāna- could be from Sinhalese nahā(e.g. nahāna-) or vice versa for in the Sinhalese script conjunct consonants are placed side by side, rather than one hanging below the other. 22 Writing style that lacks word breaks • • • • – a bold correction to SN I The puzzling words, nāgavatā, sīhavatā, ājānīyavatā, nisabhavatā, dhorayhavatā and dantavatā (Sutta no. 38) The commentator innovated the meaning nāvgavatā ti nāgo viya. A Lannā manuscript reads: sīho vatā. Emended the text to: nāgo va, tā ca pan’ uppannā sārīrikā vedanā …adhivāseti; sīho va, tā …. • Later correction: just adding a space to read: nāga va, tā ca …. • The Commentator who misread and misinterpreted is the culprit. He should have glossed: nāvgavā ti nāgo viya. 23 Grammar Correction • corrected rāja-kosaṃ to rājā kosaṃ. • The corrected sentence (p.207) reads: <tass’ eva kammassa vipākāvasesena idaṃ sattamaṃ aputtakaṃ sāpateyyaṃ rājā kosaṃ paveseti> – [By the remaining maturation of that same action, this is the seventh time that he has had no children and the king enters his property into the treasury]. • Only S4 reads <rājā kosalaṃ>; others rāja-kosaṃ. Here the corruption process was rājākosaṃ (no word break) > rājakosaṃ. • The variants for paveseti are Te.L1.B2 pavesenti; B1.B3 pavesanti; S4 pasevaseti; others paveseti. – Paveseti > pavesenti (bad memory)> pavesanti (dropping diacritic) – Paveseti > pasevaseti (metathesis and correction) 24 Phonetic Confusions via Mishearing • Phonetic confusions occur when a copyist transcribes his manuscripts at someone else’s dictation. • The variant jaṅgamānaṃ pāṇānaṃ [moving animals] for jaṅgalānaṃ pāṇānaṃ [forest animals] (p.195). • The writing of non-aspirate for aspirate, dental for retroflex, and vice versa also belongs to this category of mistakes. • See p. 225: nippoṭhento [crushing] (Be.Ce) > nipphoṭhento (Sa.C1), nippothento (Te.B2.B3), nipphothento (B1.L1.C3), nipphoṭento (R.S4.S5), and p. 211: khañjo [lame] > kañjo (S4). 25 Unfamiliar to Familiar Words • Substituting synonyms or familiar words for unfamiliar ones corrupts the archaistic character of the text. • Notice subhagiyā of v. 409c: tādisā subhagiyā putto [son of such a noble woman] having subhariyā (R.Te.B2.B3) and bhariyā (L1) as variants. • Another example: in the verse 28, brahāraññaṃ [great forest] has the variant mahāraññaṃ. 26 Haplography • The omission of words or syllables with the same beginning or ending. • mama bhattābhihāre [while I am taking my dinner] has the variant mamābhihāre [at my offering]. • the long ā of bhattā- and bh of both bhattā- and – bhihāre have contributed in generating this error or variant. • On p. 211, the variant lohitamālā vā lohitamālā gaccheyya (S4) for lohitamālā vā lohitamalaṃ gaccheyya. • When copying the second lohitamalaṃ, the copyist read the lohita- and took another look and read the ending of the first -mālā again. 27 Missing Superscripts • Omission of letters and the superscript vowel signs is a frequent error type which sometimes breeds further corruptions. • v. 517: gotamā ti has the variant: gomā ti (O cattle owner) which also corrupts the metre. • On p. 207, three readings could be line up as seṭṭhittaṃ > seṭṭhattaṃ (S2.S3.S4) (loss of diacritic)> seṭṭhaggaṃ (B1.B2.B3), last being the second stage of corruption. • Such errors could be due to faulty hearing as well. 28 Missing One or Two Syllabic Words • Omissions or insertions of seemingly unimportant words such as ca, pi, kho, ati, adhi, etc could also be noticed. 29 Glosses Coming into the Text • The insertion of interlinear or marginal glosses or notes. • v. 256d: sucetaso asito tadānisaṃso ti has a variant anissito for asito. • Tuṭṭhubha metre requires asito here. • the word anissito could be an interlinear or marginal gloss coming into the text. 30 False Recollections • When the scribe sees a familiar word or phrase or passage in his exemplar, it may suggest to him something else and then what he writes down is what is in his mind, rather than what is before his eyes. • p. 277, we read: atha kho ragā ca māra-dhītā bhagavato santike imaṃ gāthaṃ abhāsi. • the variants: gāthāya ajjhabhāsi (Be.Te); imāya gāthāya ajjhabhāsi (B2.B3); imā gāthāyo abhāsi (L2). • v. 514d reads: acchejja nessati maccu[rāja]ssa pāran ti. • Tuṭṭhubha detects detects –rāja- of maccurājassa does not fit here, and so we could decide that the original reading was maccussa. 31 Transposition • Transposition of one or more syllables, words, phrases, lines or passages. • the copyist finds he has accidentally omitted a line and then writes the omitted portion in the margin, usually adding a sign to show where it should come. • The succeeding copyist overlooks this sign and permanently misplaces the portion of the text. • verse 397: naḷhaṃ na taṃ (B2) appears for na taṃ daḷhaṃ. • The copyist first copied na of na taṃ but then positioned his eyes on ḷhaṃ of the exemplar and copied ḷhaṃ and then again he positioned his eyes on na taṃ and copied na taṃ creating this corruption. 32 Orthographic Spellings • We also find the copyists making their choice between two orthographic spellings: • nahāyeyya <> nhāyeyya (Te.S5.B2.B3) (p.204), • byādhayissanti <> vyādhayissanti (R.S4.S5) (v. 709c). 33 Metre as a Tool • • • • • • • • • The Suttapiṭaka contains over 20,000 verses SN I has 945 verses. a text with verses (sagāthaka). 731 (77%) verses in the simple Śloka (vatta) metre with its several variations known as vipulā. 124 (13%) in Tuṭṭhubha. The rest (10%): Vetālīya (22 verses), Vegavatī (9), Tuṭṭhubha-Vatta (5), Tuṭṭhubha-Jagatī (16), Jagatī-Vatta (1), Brahati-Vatta (2), Ariyā (Āryā) (4), and Panti (2). At the time I noted from the classical metrical point of view, 21 verses as metre unknown. Norman points out their meters are known. I now agree with some of his identifications. 34 Vatta Metre • consists of 4 (sometimes 6, rarely 5) pādas with 8 syllables (akkhara) in each line, organized in dissimilar pairs (prior and posterior) which are repeated to make up a verse. • 9 syllables possible due to resolution (two shorts in the reading counted as one long). • The prior line: (1) U or ― or UU (2) U or ― (3) U or ― (4) U or ― (5) U (6) ― (7) ― (8) U or ―; • the posterior line: as before except the cadence (5) U (6) ― (7) U (8) U or ―. • In the prior line (2) U (3) U (4) U as well as (2) U (3) U (3) ― are avoided. • The posterior line also follows the same rule and in addition, it avoids also (2) ― (3) U (4) ―. 35 Meter as a trustworthy guide The verse 52 reads: • sattiyā viya omaṭṭho - ḍayyamāno va matthake ―U―U/U――― ―U――/U―U― • sakkā-diṭṭḥi-pahānāya - sato bhikkhu paribbaje ti. ―――U/U――U U――U/U―U― – [A monk should wander about as if pricked by a dagger, as if his head were on fire, mindful, in order to give up the personality belief]. • Its pāda c has 6 variants: L1: sakkā-diṭṭhi-pahānāya; L2: sakkādiṭṭhi-ppahānāya; S2.S4: sakkāya-diṭṭhi-ppahānena; B2.B3: sakkāya-diṭṭhi-pahānena; R.Te.Se.S5.Be: sakkāya-diṭṭhi-pahānāya; Thag: bhava-rāga-pahānāya. • Sakkāya does not scan as Vatta (normal); so the truncated form sakkā (-āya > -ā, see von Hinuber #142) was chosen, and the reading is found in L1.L2. • This verse and what goes before (51) are found in Thag 39—40, 1162—3 with the reading bhava-rāga-pahānāya in 40c and 1163c. 36 Tuṭṭhubha-Jagatī mixture • The verse 54: yo appaduṭṭhassa narassa dussati - suddhassa posassa anaṅganassa ――U――UU―U―U― (12) ――U――UU―U―― (11) tam eva bālaṃ pacceti pāpaṃ - sukhumo rajo paṭivātaṃ va khitto. U―U――UU―U―― (11) ――U―UU――U―― (11) – [Whoever offends against an unoffending man, a purified man without blemish, the evil rebounds upon that self-same fool, like fine dust thrown against the wind]. • Its pādas bcd scan as Tuṭṭhubha, with c scanning pacceti UU―U (pati-eti) and d scanning sukhumaṃ ―― (sukhumaṃ); but pāda a scans as Jagatī. 37 Change or Not? • The issue is whether to keep the pāda a as Jagatī or change it to a Tuṭṭhubha. Here we find the same verse in Dhp 125, Thag 783, Sn 662, Ja III 203, Pv 24, Vism 301—2, and also a parallel in Udv 28:9 where pāda a scans as Jagatī: • yo hy apraduṣṭasya narasya duṣyate - śuddhasya nityaṃ vigatāṅganasya, ――U――UU―U―U― (12) ――U――UU―U―― (11) • tam eva bālaṃ pratiyāti pāpaṃ - kṣiptaṃ rajaḥ prativātaṃ yathaiva. U―U――UU―U―― (11) ――U―UU――U―― (11) • Further, nearly 16 verses in this combination of Tuṭṭhubha-Jagatī are found in SN I, a variation, as noted by A.K. Warder, that we find in the middle period of the formation of the Pāli canonic texts. So we cannot change the last word of pāda a to suit to Tuṭṭhubha line. 38 • Tuṭṭhubha = 11 syllables to a line: (1) U or ― or UU (2) ― (3) U (4) ― (5) U or ― (6) U (7) U or ― (8) ― (9) U (10) ― (11) U or ―; • Jagatī = as Tuṭṭhubha but has an extra short syllable in penultimate positing: (11) U (12) U or ―. 39 Confirming the Readings • The metre helps confirming the readings in the manuscripts. • The verse 403 is in Vetālīya, a mattāchandas, which is not so common metre in SN I: • manujassa sadā satīmato - mattaṃ jānato laddhabhojane UU―UU/―U―U― (14) ―――UU/―U―U― (16) • tanu tassa bhavanti vedanā - saṇikaṃ jīrati āyu pālayan ti. UU―UU/―U―U― (14) UU――UU/―U―U― (16) – [If a man is always mindful, and knows moderation in the food he takes, his pains diminish, and the food is digested slowly, preserving his longevity]. • The metre confirms that we should read satīmato not the variant satimato; o of jānato should be read short though it is an open syllable. • Though the Ja II 294 reads tanū tassa in line c, here we should read tanu tassa. • The variant tanukassa is definitely due to the familiar word tanuka [very small] and also due to the careless handwriting making it difficult to distinguish between ta and ka. 40 Vegavati and Vetālīya • A rare metre in SN I is Vegavatī and it differs from Vetālīya only with reference to the cadence. Notice the verse 712 where again o of open syllable should be read short. aratiñ ca ratiñ ca pahāya - sabbaso gehasitañ ca vitakkaṃ UU―UU/―UU―― (14) ―UU―UU/―UU―― (16) vanathaṃ na kareyya kuhiñci - nibbanato arato sa hi bhikkhu. UU―UU/―UU―― (14) ―UU―UU/―UU―― (16) – [Giving up liking and disliking entirely, and thought connected with the householder’s life, one should not crave for anything. For he is a monk who is without craving, without delight.]. – Notice Thag 1214d: nibbanathā avanatho sa hi bhikkhu. 41 The words that do not scan • Certain Pāli words create metrical problems. For example, aparaddho (verse 446; see Sn 891b and Thag 78b) does not scan. 42 Parallel Readings • Parallels were used as a support in editing the text. – Parallels of SN I are found in Six Jātaka volumes, Suttanipāta, Theragāthā, Therigāthā, Dhammapada, Itivuttaka, Udāna, Vinaya I and II, Aṅguttaranikāya I, II, III, and V, Majjhimanikāya II and III, Dīghanikāya II, Saṃyuttanikāya II and Milindapañha. – Further, parallels in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit texts: Udānavarga and the Mahāvastu, are also found. • I have added <no> to read v. 523a: itthibhūto <no> kiṃ kayirā [what difference does it make to be a woman?, no of nu, emphatic and interrogative particle], going against all manuscript evidence but following Thīg 61. • As it is in Pathyā vatta verse, we should read <no> short (U), perhaps <nu> and disregard the svarabhakti vowel of kayirā to have ――. 43 Repetitions • Within the SN I, the following two verses appear in four different suttas: – • kiṃsu jhatvā sukhaṃ seti kiṃsu jhatvā na socati kissassa eka-dhammassa vadhaṃ rocesi Gotamā ti. – • (1) As conversation between a deity and the Buddha (Sutta 71); (2) between Māgha (a god) and the Buddha (84); (3) between Bhāradvājagotta (a brahmin) and the Buddha (187); (4) between Sakka and the Buddha (267). [After killing what does one sleep well? After killing what does one not grieve? O Gotama, what is one thing which you approve of killing?] kodhaṃ jhatvā sukhaṃ seti kodhaṃ jhatvā na socati kodhassa visamūlassa madhuraggassa devate/ vatrabhū/brāhmaṇ/ vāsava vadhaṃ ariyā pasaṃsanti taṃ hi jhatvā na socati. – – [After killing anger, one sleeps well; after killing anger, one does not grieve. O deity, noble ones praise the killing of anger which has poison at its root and honey on top; indeed after killing it, one does not grieve.] In GDp 288—9: ki nu jatvā suho śayadi – ki nu jatvā na śoyadi, kisa nu ekadhamasa – vadha royeṣi godama. kodhu jatvā suha śayadi – kodhu jatvā na śoyadi, kodhasa viṣamulasa – masuragasa bramaṇa, vadha ari’a praśajadi – ta ji jatva na śoyadi. See Brough’s note on these verses at GDp where he says that jhatvā is a synonym of hantvā and questions PED’s connecting jhatvā with jhāpeti (to burn). Cf. Ja V 141: kiṃ sū vadhitvā na kadāci socati …; kodhaṃ vadhitvā na kadāci socati … 44 Introductory Passage • Introductions are mostly repetitive. Sometimes the same verses are repeated in two suttas differing only the introductions (see for example, the suttas 250 and 251 occurring in the Sakkasaṃyutta). 45 Two New Verses • Two verses found in Lanna manuscripts were placed in the SN I for the first time in an edition. • The verse 70 (parallel at Ja II 233) is one. • gharā nānīhamānassa gharā nābhaṇato musā gharā nādiṇṇadaṇḍassa paresaṃ anikubbato evaṃchiddaṃ durabhibhavaṃ ko gharaṃ paṭipajjhatī ti. – [There is no home for him who makes no effort; no home for the one who does not lie; no home for him who does not use violence towards others or cheat them. Who would like to follow home life with such defects, hard to sustain?] • This constitutes a question put to the Buddha by a deity, but lost in the other manuscript traditions. • Other traditions made one verse from the answer a question by changing the word te to ke or ko. 46 The verse 138 • The verse 138 was added to the text, though I now somewhat regret. • jīvitaṃ byādhi kālo ca deha-nikkhepanaṃ gati pañc’ ete jīva-lokasmiṃ animittā na ñāyare. – (Life, sickness, time of death, laying down the body, passing to the next life, these five things in this world of the living are not recognized because they come unheralded.). • This verse was also added based on the two Lanna manuscripts. A parallel is found at Ja II 58. 47 Verse 2 • • corrected going against all mss except L2. nandībhavaparikkhayā saññāviññāṇasaṅkhayā vedanānaṃ nirodhā ca upasanto carissatī ti. evaṃ khvāhaṃ āvuso jānāmi sattānaṃ nimokkhaṃ pamokkhaṃ vivekan ti. – [Through extinction of delight and becoming, through destruction of apperception and consciousness, and through stopping sensation, one will live tranquil. That is how I understand the deliverance, freedom, detachment of beings.] • • • Of pāda c, L2: vedanānaṃ nirodhā ca upasamā; L1.R.Se.Be.Te.B3.S1-5.N: vadenānaṃ nirodhā upasamā; B1.B2: vedanā nirodhā upasamā. Pāda d, L2: esa upasanto carissatī ti. All others omit. The verse here is corrupt; hence the metre is difficult to restore. Further, the last pāda is very doubtful since it is found only in L2. The parallel with Sn 175c, suggests emendation of pāda a to nandībhavaparikkhīṇo. The word parikkhayā could be due to the influence of -saṅkhayā in the next pāda. 48 Conclusion: What My Editing Experience Taught Me • The editor of the Pāli canonic texts should not attempt to see a coherency and consistency throughout the text; rather he should collect all the existing variants that appear in the most trustworthy and representative manuscripts and use his or her common sense to visualize the process of corruption in the existing variants in order to select the plausible earliest reading that which has given rise to others. • Trying to apply one or a fixed set of rules to edit the whole text with the aim of putting together a coherent piece of text would be disastrous to a Pāli canonic text that is multifarious, flexible, dynamic and creative in terms of its structure, language, and the content. 49 • For example, the SN I is a geyya text consisting both prose and verse, and considering its inclusion of verses in early metres, particularly the Vatta, it is reckoned as one of the earliest texts, perhaps that could be placed just below the Aṭṭhaka and the Pārāyana Vaggas of Suttanipāta, of the Pāli canon. – As Warder’s Pāli Metre suggests, these verses demonstrates the transition period from early Vedic metres to classical ones. • SN I is a collection of Suttas containing verses, arranged under different groups known as saṃyuttas, compiled into one text over a period of time. – This is evident from its imbalanced size of different saṃyuttas. • Pāli language bears close affinity to a few vernacular dialects at the time, and the SN I contains also some eastern characteristics such as bhikkhave (vocative plural), sa, nāga (nominative singular) etc. • Much of its content is about prescribed rules of law, good actions, and good behavior (dhamma) that are in tune with the profound laws of nature, the continuity of processes by way of arising and ceasing, with no everlasting entities (dhamma). 50