Educause presenation

advertisement

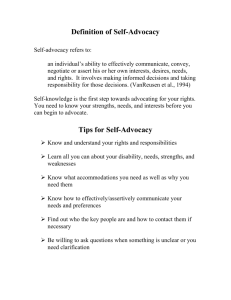

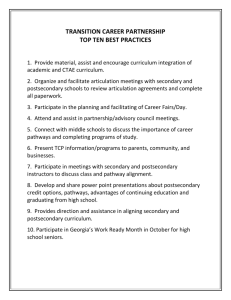

Opportunities for Postsecondary Success for College Students with Intellectual Disabilities AHEAD Conference July 15, 2011 Cathy Schelly, M.Ed., OTR/L; Assistant Professor Director, Center for Community Partnerships PI, OPS Project Julia Kothe, M.Ed. Assistant Director, Center for Community Partnerships Self-Advocacy Coordinator Project Opportunities for Postsecondary Success Who we are… Center for Community Partnerships — a service and outreach arm of the Department of Occupational Therapy at Colorado State University …Supporting the inherent dignity, potential and full participation of all people. DOE, OPE-Funded Program Focus Areas Opportunities for Postsecondary Success (OPS) — student supports Student Self-Advocacy leading to success for students with ASD UDL, AT and SA instruction and technical assistance Program evaluation, dissemination, replication Universal Design for Learning: 3 Principles 1. Instructors represent information and concepts in multiple ways (and in a variety of formats). 2. Students are given multiple ways to express their comprehension and mastery of a topic. 3. Students engage with new ideas and information in multiple ways. Represent Graphic of merging UDL and SA Till the cows come home… Instructors can implement UDL and best teaching practices until the cows come home... But until students become aware of how they learn, what they need to be successful in the college environment, and how to put strategies and resources in place to promote success—until they become self-advocates— we’re only half-way to our goal. Self-Advocacy “Self-advocacy is the ability to understand one’s own needs and effectively communicate those needs to others.”* OPS Self-Advocacy Definition* Knowing yourself Knowing what you need and want Strengths, interests, challenges Available resources, accommodations Knowing how to get what you need and want Taking action Self-Advocacy Skill Development for Postsecondary Success Why Promote Self-Advocacy? Academic Persistence! Self-advocacy is a key predictor of student success. Strong self-advocates (self-responsible learners) tend to experience greater academic satisfaction, higher grades, and have an increased level of ability to succeed in college and in life.* 1 The problem… “Too many students with disabilities exit high school with limited selfdetermination and self-advocacy skills because school and parents assume responsibility for advocating for educational needs rather than fostering the development of these skills in students.”* Differences between high school and college/university High School (IDEA) College (504 and ADA) Class sizes are usually small Class sizes may be large Students receive reminders and support for assignments Students expected to complete their work independently Child Find Student must take initiative to seek out accommodations Indiv. Education Plans (IEPs) Self-advocacy Students’ time is managed for them Time management skills needed Teachers are available for assistance and questions during and after class Professors are available during office hours The solution... UDL + Self-Advocacy = ACCESS Inclusive instruction through UDL implementation makes learning accessible to all students. Becoming an effective self-advocate is critical for success in postsecondary education – for all students, and especially those with ASD! Self-advocacy skill development is the foundation of support strategies for students with ID, including ASD and TBI/ABI! ACCESS Leads to Questions and Program Development Who are the students who are ‘falling through the cracks?’ Why are they struggling? How can we best support high-risk students with ID (including ASD and TBI) to promote success in achieving their postsecondary dreams? Office of Postsecondary Education provided the potential answer to our questions. Transition Program Funding Priority Authorized by Higher Education Opportunities Act (HEOA) Reauthorization in 2008 (PL 110-315) IHEs funded to develop comprehensive transition and postsecondary programs for students with disabilities that impact their cognitive functioning Transition Program Funding Priority HEOA focus: Students with learning/academic functioning impairments, characterized by significant limitations in cognitive functioning and/or adaptive behavior as expressed in conceptual, social, and/or practical adaptive skills, including students with ASD Addressing a need identified at CSU, FRCC, PSD and beyond OPS supports and services – enhanced program OPS focuses on supporting successful postsecondary transition outcomes for students with disabilities who need additional support above and beyond academic accommodations provided through the Resources for Disabled Students Office at Colorado State University. What types of services? Weekly goal-setting and strategizing meetings with a Transition Coordinator and/or a Peer Mentor Individualized assessment for identification of challenges, needs, strengths, interests and goals Connecting students to campus resources Identifying and implementing compensatory strategies and/or accommodations that promote self-advocacy and academic and campus life success Modeling and practicing of social and interpersonal skills as needed Critical skill development - time management, organization, communication, problem-solving, decision making, stress management, study and test taking skills, career path planning, recreation resources, etc. Center for Community Partnerships Implementing OPS CCP partnering with: OT faculty CSU Assistive Technology Resource Center CSU Student Disability Office Student Affairs Residential Life Local Community College Colorado School Districts Developmental Disability System (CCB) Division of Vocational Rehabilitation City Adaptive Recreation Program OPS Goals Transition supports, with a SA focus Transition Coordination Peer Mentoring UDL, AT, and SA training and technical assistance Evaluation of program outcomes Who are the students ‘falling through the cracks’ of higher education? TBI Facts Who is at highest risk for TBI? Males are about 1.5 times as likely as females to sustain a TBI. The two age groups at highest risk for TBI are 0 to 4 year olds and 15 to 19 year olds. Certain military duties (e.g., paratrooper) increase the risk of sustaining a TBI. African Americans have the highest death rate from TBI. The Brain Injury Alliance of Colorado, June, 2011 BI Facts The leading causes of BI are: Falls (28%) Motor vehicle-traffic crashes (20%) Struck by/against (19%) Assaults (11%) Blasts are a leading cause of TBI for active duty military personnel in war zones. Illness, cancer, stroke, congenital conditions, etc. (ABI) The Brain Injury Alliance of Colorado, June, 2011 Possible Physical Changes Following BI Fatigue – longest residual symptom Motor speed and coordination, balance Depression Sleep disruption Appetite, diet, exercise changes Bladder, bowel control Regulation of body temperature Medication side effects Sensory/perception Slowed, slurred speech Seizures Paralysis, spasticity Pain Possible Cognitive Changes Following BI Difficulties with: Problem solving, word finding Variable abilities/performance Initiation, sequencing, followthru, self monitoring New learning, abstract principles Receptive, expressive language Attention, concentration Mental processing Short term memory (fatigue, time of day, stress, overstimulation…) Adapting to changes in life Organization, planning, time management Impulsivity, impaired judgment, safety awareness Multi-step directions Possible Social-Behavioral Changes Following BI Difficulties with: Personality changes Emotional regulation Self-awareness Depression, lethargy, stress, withdrawal Impulse control, distractibility Lack of inhibition, inappropriate behaviors Interpretation of social cues (facial, verbal, sarcasm, figures of speech…) Awareness of others Self concept/esteem – “I just want to be like I was before!” Inflexible thinking Anxiety, irritability, aggression Dependency – other people, drugs, alcohol BI Scenario Josh is referred to the OPS program as a sophomore because he is experiencing difficulties with his ichthyology and wildlife management classes. He experienced a brain injury when he was in elementary school and as a result, has short-term memory challenges, takes medication for headaches every night, becomes fatigued after an hour and half of studying, and has poor balance. Upon meeting with Josh you find out the following: He did well in high school and maintained a 3.0 as a freshman in college. He looked into assistive technology accommodations, but never followed through. He is getting a D in his ichthyology and wildlife management classes. He has not met with the professors of these two classes. He is embarrassed by his disability and doesn’t want other students to find out about his brain injury. He described a situation with his ichthyology class when the class was collecting samples from a stream. Several times he almost fell into the water due to his unstable balance. He is lonely and feels isolated. Recommendations? What recommendations do you have for this student? What are we hoping to accomplish? Is it just academic support that this student needs? Support from the Transition Coordinator? Support from the Student Mentor? Taking a close look at the college student with ASD Coming to universities and colleges in record numbers IEPs in high school (or 504 plans) High functioning re: academic skills Potential difficulties with activities of daily living, relationships, socialization IHEs feeling sense of urgency in determining how to best support these students Through OPS, we are develop support strategies as well as institutional accommodations to address the needs of this growing student population! Strengths that students with ASD may have* Cognitive abilities similar to neurotypical or gifted individuals Excellent vocabulary, strong verbal skills Focused, diligent Honest to a fault Strong desire to excel Creative, unique ways of thinking Passionate about unique interests Concrete literal Challenges that students with ASD may experience1 Difficulty with change, transitions Poor ability to read/learn unwritten rules and procedures Frequent situational anxiety Difficulty with communication, relationships, reciprocal social interaction including body language, eye contact, and spatial awareness. (e.g. roommates, classmates, group assignments, class presentations) Presence of stereotyped behavior, interests or activities Sensory processing disorders2 Concrete literal Very ConcreteLiteral Possible areas of confusion What is the difference between three and four credits? What does it mean to add/drop a course vs. withdraw from a course? What are the unwritten rules? Why can’t I keep texting my roommate? What do I do with the assignment when I’m finished? What am I supposed to do when a class is cancelled? ASD Scenario In the second semester of her freshman year, Sally, a student with Asperger’s, is referred to the OPS program because she is experiencing a lot of anxiety and is struggling academically. She is especially worried about her grade in Chemistry. Upon Meeting Sally you find out the following: She did well in high school. She took engineering classes first semester on a pass/fail basis and passed these classes. She has not been attending her Chemistry class or lab. At the beginning of the semester she had a university conduct hearing for stalking behaviors. She is worried that she will be kicked out of school. She is also worried that her family will stop supporting her. She is connected with the disability service office and a university case manager. She would like to have a boyfriend. Recommendations? What recommendations do you have for this student? What are we hoping to accomplish? Is it just academic support that this student needs? Support from the Transition Coordinator? Support from the Student Mentor? If you know a student with BI or ASD… …you know a student with BI or ASD! Addressing Problem Areas Organization Selecting Courses Social Life Living in the Residence Halls Daily Living Prepare in Advance Sensory Issues Self-advocacy Addressing Problem Areas Supports for eligible HS students who are headed to college/university Transition Coordinators/Peer Mentors assist with: Connection and familiarization with campus locations and resources (individualized) Introduction to residence hall, RA – identification of residential support needs Learning the ropes: signing up for classes, understanding add/drop/withdrawal rules, course management system Development of compensatory strategies Development of self-advocacy skills Supports for eligible college students Transition Coordinators/Peer Mentors assist with: Development of relationship/friendship with roommate, classmates Socialization guidance, role playing Development of skills for group assignments Identification of ‘triggers’ – coming up with crisis management strategies Connection to recreation, activities Career exploration Development of compensatory strategies Development of self-advocacy skills Finding, Getting and Keeping a Job: An OPS Focus Area Preparing for an internship interview Shaking hands properly Looking and acting professional Eye contact Hygiene Research company in advance Positive answers to boilerplate questions… Tell me about your strengths… What to say, what not to say… Describe how you are as a team player a. Teams are kind of bad. Sometimes people don’t know what they’re doing. Sometimes everyone is working on the same thing. And sometimes one person does all the work. b. I have been on many teams, working on group assignments in some of my classes. I do well on teams when I know what my role is – then I can get my part done and contribute to the team effort. c. I’d rather work by myself. d. Teams are not my favorite thing, but I’ll be on a team if I have to. Why should we hire you? a. I have taken numerous courses in topics that relate to your business and received a good grade in all of those courses. b. I am guessing that I am the smartest applicant. c. Because I read about this stuff for fun. I love it. This is what I do, what I think, what I know. I love it. d. Because I turned in my application on time and now I’m here for the interview. How can we establish and document measurable goals with college students? Why establish measurable goals? Accountability To determine if intervention is effective To make improvements in services based on data To allow students to realize that improvements are occurring To prove that these students CAN be successful as college students, with the right supports in place! How can we establish and measure goal attainment? Goal Attainment Scaling Goal Attainment Scaling Goal attainment scaling (GAS) is an individualized approach for measuring the achievement of goals (King et al., 1999). GAS was originally developed to assess adults in a community mental health setting, but has since been applied to numerous practice areas, including education, health, and social work (MacKay, Somerville, & Lundie, 1996). Original goal attainment scaling method The original GAS scale uses a 5-point scale, ranging from -2 to +2, with zero representing the expected level of performance after intervention. Levels Kiresuk, Smith, & Cardillo (1994) -2 Much less than expected outcome -1 Somewhat less than expected outcome 0 Projected level of performance +1 Somewhat more than expected outcome +2 Much more than expected outcome Applying GAS in practice Involves… 1. Identifying the overall objective 2. Identifying the specific problem areas that should be addressed 3. Specifically identifying the behaviors or events that will indicate improvement in each area 4. Determining the methodology that will be used to collect the desired information 5. Identifying outcomes for scaling 6. Determining the client’s current status and how progress will be documented What is the overall objective? Set the expected level of outcome or the desired goal to be attained by the student, as well as the timeframe for goal attainment Goals should be: Student driven Realistic What are the specific problem areas? This requires prioritizing areas of concern and formulating goals that are SMART When goals are prioritized they are also given a weight, which is used to convert the scale score into a standard score What are SMART goals? Specific= a specific goal has a much greater chance of being achieved. It is the who, what, where, when, which, and why of the goal. Measurable=establish concrete criteria for measuring progress. Attainable=help client’ set goals that are meaningful to them and that they want to achieve. Relevant=a goal must represent an objective toward which you are both willing and able to work. Time-specific=a goal should be grounded within a time-frame. Tips for scaling goals… Select the expected level of performance Identify the least favorable outcome and the most favorable outcome Identify the intermediate levels of performance Set goals that are SMART Establish a scale with measurable intervals GAS example Goal Area: Career exploration Current level of attainment 0 Baseline: Has no idea of what field/career to pursue. Much less than expected 1 Has not chosen any preferred fields, but has done exploration Somewhat less than expected 2 One or more fields chosen, but no planning Expected level of outcome 3 Selected one or more fields with plans for achieving at least one Somewhat more than expected 4 Has followed through with a plan Much more than expected 5 Acquired internship or job in a selected field or related area Goal Attainment Scaling Exercise Establishing SMART goals for Josh Establishing SMART goals for Sally Josh Goal Area: Current level of attainment 0 Baseline: Much less than expected 1 Somewhat less than expected 2 Expected level of outcome 3 Somewhat more than expected 4 Much more than expected 5 Sally Goal Area: Current level of attainment 0 Baseline: Much less than expected 1 Somewhat less than expected 2 Expected level of outcome 3 Somewhat more than expected 4 Much more than expected 5 Advantages of using GAS with the OPS project Provides a quantitative measure of outcome Can be used to compare a student’s progress over time Can be used to compare performances across students in the same program (Ottenbacher & Cusick, 1989). Allows for a collaborative approach-working with the student to set realistic goals Provides flexibility for measuring diverse outcomes (Brown, 2009). Limitations of GAS It is important to be aware of the potential limitations prior to implementation Scaling can be a time-consuming process Biases can occur in goal setting, scaling, and rating Temptation to modify goals throughout the course of intervention Conclusion As educators, it is our responsibility to support and empower students with disabilities who are coming to college, seeking employment, pursuing their dreams… With the supports we are providing these students, we are facilitating their… …opportunities for postsecondary success Self-Advocacy Resources accessproject.colostate.edu ccp.colostate.edu UDL Modules Universally designed Word, PowerPoint, HTML and PDF SA Resources Disability Information for Faculty SA Handbook for College Students with Disabilities (helpful information for students, parents, secondary education teachers and counselors, university faculty) Transition Checklist Thank you! Cathy Schelly catherine.schelly@colostate.edu 970-491-0225 Julia Kothe julia.kothe@colostate.edu 970-491-3469 References Barnhill, Hagiwara, Myles & Simpson (2000). Asperger syndrome: A study of the cognitive profiles of 37 children and adolescents. Forum on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15(3), 146-153. Burgstahler & Cory (2008). Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press. Field, Sarver & Shaw (2003). Self-Determination: A Key to Success in Postsecondary Education for Students with Learning Disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 24(6), 339-349. Glennon (2001). The stress of the university experience for students with Asperger Syndrome. Work, 17, 183-190. References Izzo & Lamb (2002). Self-determination and career development: Skills for successful transition to postsecondary education and employment. A white paper for the Post-School Outcomes Network of the National Center on Secondary Education and Transition (NCSET) at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. http://www.ncset.hawaii.edu/Publications/ King, G.A., McDougal, J., Palisano, R.J., Gritzan, J., & Tucker, M.A. (1999). Goal attainment scaling: its use in evaluating pediatric therapy programs. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, p. 3152. Kiresuk, T.J., Smith, A., & Cardillo, J.E. (1994). Goal Attainment Scaling: Application, Theory, & Measurement. Hilldale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Lotkowski, Robbins, Noeth (2004) The Role of Academic and Nonacademic Factors in Improving College Retention. ACT Policy Report. References Mailloux, Z., May-Benson, T.A., Summers, C.A., Miller, L.J., BrettGreen, B., Burke, J.P., et al. (2007). The Issue Is-Goal Attainment Scaling as a measure of meaningful outcomes for children with sensory integration disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 254-259. McKay, G., Somerville, W., & Lundie, J. (1996). Reflections on goal attainment scaling (GAS): cautionary notes and proposals for development. Education Research, 38,2, 161-172. National Center for Education Statistics, 2008 Ottenbacher, K.J. & Cusick, A. (1990) Goal attainment scaling as a method of clinical service evaluation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 44, 6, 519-525. References Rose, D., et al. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19(2), 135-151. Schelly, C., Davies, P., & Spooner, C. (2011). Student Perceptions of Faculty Implementation of Universal Design for Learning. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24(1), 17-28. Shore, S. (2010). Helping your child to help him/her self: Beginning self-advocacy (Autism Asperger.net). Retrieved 3/7/11 from http://www.autismasperger.net/writings_self_advocacy. Steenbeek, D., Ketelaar, M., Galama, K., & Gorter, J.W. (2007). Goal attainment scaling in pediatric rehabilitation: a critical review of the literature. Dev Med Child Neurol, 49, 550-556. References Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the cause and cures of student attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago. Turner-Stokes, L. & Williams, H. (2010). Goal attainment scaling: a direct comparison of alternative rating methods. Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation, 24, 66-73. U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2009. VanBergeijk, E., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F. (2008). Supporting more able students on the autism spectrum: College and beyond. Journal of Autism Developmental Discord, 38, 1359-1370.