File

advertisement

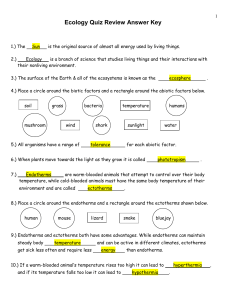

Controlling Body Temperature Body Temperature and Homeostasis For muscles to operate quickly and efficiently, for example, their temperature can neither be too low nor too high. If muscles are too cold, they may contract slowly, making it difficult for the animal to respond quickly to events around it. If an animal gets too hot, on the other hand, its muscles may tire easily and other body systems may not function properly. Because most chordates are vertebrates, and mechanisms for controlling body temperature are well developed among vertebrates, this section will focus exclusively on that group. The control of body temperature is important for maintaining homeostasis in vertebrates, particularly in habitats where temperature varies widely with time of day and with season. Vertebrates have a variety of ways to control their body temperature. All of these ways incorporate three important features: a source of heat for the body, a way to conserve that heat, and a method of eliminating excess heat when necessary. In terms of how they generate and control their body heat, vertebrates can be classified into two basic groups: ectotherms and endotherms. Ectothermy Ectotherm—An animal whose body temperature is controlled from within. Birds and mammals are endotherms, which means they can generate and retain heat inside their bodies. Endotherms have relatively high metabolic rates that generate a significant amount of heat, even when they are resting. Birds conserve body heat primarily through insulating feathers, such as down. Mammals have body fat and hair for insulation. Mammals can get rid of excess heat by panting, as dogs do, or by sweating, as humans do. Comparing Ectotherms and Endotherms Each strategy has advantages and disadvantages in different environments. For example, endotherms move around easily during cool nights or in cold weather because they generate and conserve their own body heat. That's how musk ox live in the tundra and killer whales swim through polar seas. But the high metabolic rate that generates that heat requires a lot of fuel. The amount of food needed to keep a single cow alive would be enough to feed ten cowsized lizards! Ectothermic animals, such as the gila monster, need much less food than similarly sized endotherms. In environments where temperatures stay warm and fairly constant most of the time, ectothermy is a more energy-efficient strategy. But large ectotherms run into trouble in habitats where temperatures get cold at night or stay cold for long periods, such as boreal forest biomes. It takes a long time for a large animal to warm up in the sun after a cold night. Most large lizards and amphibians live in warm areas such as tropical rain forest biomes. Evolution of Temperature Control There is little doubt that the first land vertebrates were ectotherms. But there is some doubt as to when endothermy evolved. Although modern reptiles are ectotherms, some biologists hypothesize that at least some of the dinosaurs were endotherms. Others hypothesize that endothermy evolved a long time after the appearance of the dinosaurs, so that all the dinosaurs were ectotherms. Evidence suggests that endothermy has evolved more than one time. It developed once along the evolutionary line of reptiles that led to birds and once along the evolutionary line of reptiles that led to mammals.