Opioid Management - Minnesota Pharmacists Association

advertisement

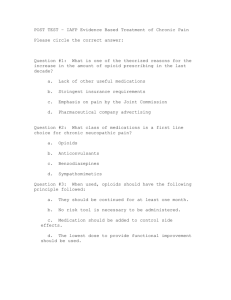

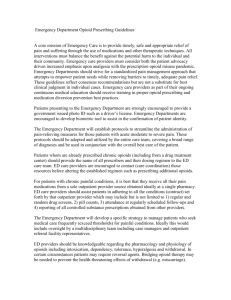

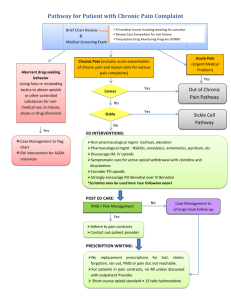

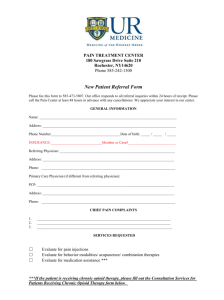

MPhA MTM Fall Symposium Kathryn Perrotta, PharmD, MBA, BCPS November 16, 2012 Define the health economic impact of the use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of pain Apply evidence based guidelines in moderate to severe chronic non-cancer pain management Address abuse, misuse and diversion reduction strategies (proper disposal options and PMP) Explore the role of ambulatory care pharmacists in primary care pain management and opportunities for collaboration with other professionals in the health care team Concern: significant increase in opioid prescriptions Sales of opioids quadrupled between 1999 and 2010 (government statistics) The annual cost associated with all types of pain, both direct and indirect costs, is estimated to be in the range of $560 to $635 billion annually in the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492. ~60 million Americans have some type of chronic nonmalignant pain ~40% of patients do NOT receive adequate pain relief Detailed History ◦ Onset, duration, quality, character of pain ◦ Ameliorating and provoking factors Pain Rating ◦ Patient self report: most reliable indicator of pain ◦ Numerous assessment tools available for pain in adults Numeric rating scales (1-10) Assessment ◦ Is pain due to reversible etiology? ◦ Identify cause of pain Reason for specialist? Rheumatoid arthritis, knee pain, headache, etc. Acute vs. Chronic Pain ◦ Has pain persisted longer than 6 weeks? IAP defines chronic pain as “pain that persists beyond normal tissue healing time, which is assumed to be 3 months” Determine Pain Mechanism (3 general types) ◦ Somatic ◦ Visceral ◦ Neuropathic Different symptoms Different treatment indicated www.icsi.org Assessment and Management of Acute Pain guidelines and Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain Guidelines. Fifth Edition, November 2011. Result of tissue damage Release of chemicals from injured cells that mediate pain and inflammation via nociceptors Typically recent onset and well localized Description of Somatic Pain Sharp Aching Stabbing Throbbing Examples Lacerations Sprains Fractures Dislocations www.icsi.org Assessment and Management of Acute Pain guidelines and Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain Guidelines. Fifth Edition, November 2011. Result from visceral nociception ◦ Solid and Hollow organs Fewer nociceptors ◦ Result in poorly localized, diffuse and vague complaints Description of Visceral Pain Examples Generalized ache/pressure Autonomic symptoms: Ischemia/necrosis Ligamentous stretching Hollow viscous or organ capsule distension N/V, hypotension, bradycardia, sweating www.icsi.org Assessment and Management of Acute Pain guidelines and Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain Guidelines. Fifth Edition, November 2011. Injury to a neural structure leading to aberrant processing Typically chronic pain caused by damage to peripheral nerves Description of Neuropathic Pain Radiating Burning Tingling “Electrical Like” www.icsi.org Assessment and Management of Acute Pain guidelines and Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain Guidelines Examples Diabetes Shingles MS Herniated discs From radiation/chemo Determine Patient’s Pain Goals ◦ If chronic pain patient may need to counsel on expectations of pain relief ◦ Assess for risk of substance abuse, misuse, or addiction Avoid Unrealistic Expectations in Chronic Pain Patients ◦ Improvement with opioids generally average < 2-3 points on average 0-10 scale ◦ Concentrate on quality of life and improving therapeutic goals Stress importance of utilizing other modalities ◦ Medications that are multi-modal in treating pain Alternative therapies www.icsi.org Assessment and Management of Acute Pain guidelines and Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain Guidelines. Fifth Edition, November 2011. Somatic Pain Visceral Pain Neuropathic Pain •acetaminophen •cold packs •corticosteroids •lidocaine patches •NSAIDs •opioids •tactile stimulation •corticosteroids •intraspinal local anesthetic •NSAIDs •opioids •gabapentin •pregabalin •corticosteroids •neural blockade •NSAIDs •opioids •TCAs •duloxetine www.icsi.org Assessment and Management of Acute Pain guidelines and Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain Guidelines. Fifth Edition, November 2011. 3. Perception of Pain McCaffery M, Pasero C. Pain Clinical Manual. 1999:21. Ascendin g input Spinothalamic tract Opioids 2 -agonists Pain Centrally acting analgesics Anti-inflammatory agents (COX-2 selective inhibitors, nonselective NSAIDs Descending Local anesthetics modulation Opioids Dorsal 2-agonists horn COX-2 selective Dorsal root inhibitors ganglion Local anesthetics Peripheral nerve Trauma Peripheral nociceptor s Opioids Local anesthetics Anti-inflammatory agents (COX-2 selective inhibitors, nonselective NSAIDs) Adapted by Dr. Todd Hess (United Pain Center) from Gottschalk et al. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1979-1984. 100 Repetitive stimulation of spinal neurons evokes an increasing level of response neuron response 80 60 40 20 0 |----0.5 Hz----| NMDA receptor antagonists block this effect Intense pain worsening over time Causes: most frequently trauma to extremity or surgery/infection Pathophysiological mechanism of CRPS is ongoing nociceptor input from periphery to CNS. ◦ Characterized by hyperalgesia, allodynia, vasomotor changes, abnormal regulation of blood flow and sweating, joint stiffness, localized skin edema Treatment of CRPS can be difficult; ◦ Often misdiagnosed and can be irreversible if undiagnosed ◦ Recommended that combined analgesic regimens (multimodal analgesia) be used to prevent CRPS • Reuben, S. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1215-1224. Burns, A. J Orthop Surgery. 2006; 14(3):280-3. A variety of different and integrated disciplines: ◦ Pharmacologic Complementary/synergistic mechanisms of action to inhibit effects of pain mediators and enhance the effects of pain modulation Non-opioids used in combination with opioids can decrease the total amount of opioid needed for pain control ◦ Acetaminophen Cox-2s, NSAIDs Modulating agents ◦ Duloxetine, TCAs, tramadol, etc. Topical agents ◦ Lidocaine patches Gabapentin ◦ neuropathic pain prevention and treatment A variety of different and integrated disciplines: ◦ Non-Pharmacologic: Exercise Massage Acupuncture Reiki Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Physical Therapy TENS therapy A) B) C) Incomplete Cross tolerance of opioids: A physiological phenomenon following use of opioids for > 2 weeks State of adaptation in which exposure to a drug decreases its effect over time Due to the different molecular entities of opioids, a person on an opioid for a long perioid of time will not be as tolerant to the effects of a new opioid Adjunctive Therapy Options Assess if the opioid is right for patient ◦ Effectiveness ◦ Adverse Effects: N/V, puritis, constipation, respiratory depression ◦ Renal metabolism/use in liver failure Be aware of incomplete cross tolerance effect of opioids ◦ Tolerance may develop to the opioid in use but may not be as marked relative to other opioids fentanyl synthetic to non-synthetic hydromorphone, hydrocodone oxycodone morphine, codeine Oxycodone Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) Tramadol Onset of Action (minutes) 10-15 (IR) 60-90 (CR) 15-30 60 Peak Response 1 hour 60-90 mins 2-3 hours Duration of Effect (hours) 4-6 (IR) 8-12 (CR) 4-6 4-6 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Renal Elimination Prolonged in Hepatic Failure Opioid Oral Onset of action Duration of Action Codeine 200 mg 15-30 min 3-4 hrs Hydrocodone 30 mg 15-30 min 4-8 hrs Hydromorphone 7.5 mg 15-30 min 4-6 hrs Methadone Varies* 30-60 min Varies Morphine 30 mg 15-60 min 3-6 hrs Morphine ER 30 mg 60-90 min 8-12 hrs Oxycodone 20 mg 10-15 min 4-6 hrs Oxycodone CR 20 mg 60-90 min 8-12 hrs *Consult APS Guidelines Hyperalgesia, myoclonus Morphine liver Analgesia M-6-G, normorphine M-3-G kidney Confusion, Sedation, Respiratory Depression Methadone Clinical Aspects ◦ 1/3 of opioid related overdose deaths while only a few percent of total opioid prescriptions ◦ Do NOT use for mild, acute or “break through pain” ◦ NOT for opioid naïve patients ◦ Long and unpredictable ½ life ◦ Multiple drug interactions ◦ QT prolongation ECG before starting and when doses >200mg/day Switching from another opioid: 70-90% reduction of equianalgesic dose Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(26):493-497. © 2012 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Transdermal system ◦ Onset of action: 12-18 hours, used Q 48 or 72 hrs ◦ Chronic, stable pain only ◦ Elimination after patch removal: 13-22 hrs ◦ Fever can result in up to 30% ↑ in drug levels ⊘ Heating pad or hot tub ◦ Not best option for catechetic pt weighing <50kg; unpredictable absorption +/or elimination Opioid Rotation: Change in opioid drug with the Indications for Opioid Rotation: goal of improving outcomes ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Occurrence of intolerable adverse effects Poor analgesia despite aggressive dose titration Change in clinical status Financial or drug availability consideration Deciding Next Specific Opioid: ◦ Past experience with different opioids, sensitivities, efficacy, etc. Fine, G. Opioid Rotation: Definition and Indications. Pain Management Today eNewsletter series. American Pain Foundation. , Quadrant HealthCom Inc. ; 2010: (1): 9. http://newsletter.qhc.com/JFP/JFP_pain032411.htm Opioid Rotation Guidelines: ◦ Calculate equianalgesic dose of new opioid ◦ Identify automatic dose reduction of 25-50% lower than calculated equianalgesic dose 50% reduction if high current opioid dose, elderly, nonwhite, or frail 25% reduction if patient not above ◦ Strategy to frequently assess initial response and titrate new dose ◦ Supplemental “rescue” dose for prn: calculate 5-15% and administer at appropriate interval Fine, G. Opioid Rotation: Definition and Indications. Pain Management Today eNewsletter series. American Pain Foundation. , Quadrant HealthCom Inc. ; 2010: (1): 9. http://newsletter.qhc.com/JFP/JFP_pain032411.htm Standard Opioid-PO Opioid Parenteral Hydrocodone 30mg NA Hydromorphone 7.5mg Hydromorphone 1.5mg Oxycodone 20mg Methadone: Consult Expert Morphine 30mg Morphine 10mg American Pain Society (APS). Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain, 6th edition. 2008. Glenview, IL 60025. 51 year old white female patient with chronic pain due to MVA Current Medications: MS Contin 30mg TID Hydrocodone/APAP 5/500 1-2 tabs qid prn (patient states she take 6 tabs/day) Atenolol 50mg qday Senokot-S 1 tab bid MD asks you to convert this patient to oxycodone due to recent increased itching and ineffective control of pain. 1) Conversion: Total oxycodone equivalent/day: 90mg morphine + 30mg hydrocodone 90mg morphine = 30mg hydrocodone = 60mg oxycodone + 20mg oxycodone 80mg (total oxycodone dose) 2) Should we suggest the total oxycodone dose or reduce? 2) Reduction of Dose: Total oxycodone equivalent/day: 80mg 80mg x 0.25 = 20 mg so reducing by 25% the total daily dose would be 60mg oxycodone 3) How do we want to give the oxycodone 60mg? Slow versus immediate release? 3) How do we want to give the oxycodone 60mg? ◦ Oxycontin 15mg TID plus oxycodone 510mg tid prn (start with 5mg) ◦ Patient would be taking 45mg + 15-30mg = 60-75mg ◦ Could switch morphine to oxycodone, keep on hydrocodone prn dose for first few days, reassess then switch to oxycodone Other considerations: 1. What other medications may this patient benefit from? 2. How would you have established this? 3. Does patient need high dose of opioid? 4. Has patient tried other modes of therapy such as stretching (Physical therapy involvement), massage, TENS unit or cognitive behavioral therapy (non-drug methods)? Essential to identify if: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Patient successful Patient might benefit more with restructuring of treatment Need treatment for addiction Benefits outweighed by harm Frequency of monitoring: ◦ Patient on stable doses ◦ Every 3-6 months After initiation of therapy, changes in opioid doses, with a prior addictive disorder, psychiatric conditions, unstable social environments Weekly basis may be necessary Chou, R, Fanciullo, G, Fine, P, et. al. Opioid Treatment Guidelines: Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: an update of Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. The Journal of Pain. 2009 Feb;10(2):113-130. Should include: ◦ Assessment and documentation of pain severity and functional ability ◦ Progression towards achieving therapeutic goals ◦ Presence of adverse effects ◦ Clinical assessment and detailed documentation for aberrant drug related behaviors, substance use and psychological issues If suspect above may need to implement: Pill counts Urine drug screening Family member/caregiver interviews Use of prescription monitoring plans Chou, R, Fanciullo, G, Fine, P, et. al. Opioid Treatment Guidelines: Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: an update of Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. The Journal of Pain. 2009 Feb;10(2):113-130. Most predictable factor for drug abuse, misuse, or other aberrant drug related behavior: ◦ Personal or family history of alcohol or drug abuse Other factors associated with aberrant drug related behaviors: ◦ Younger age ◦ Presence of psychiatric conditions Opioid therapy in these patients requires intense structured monitoring and management by professionals with expertise in both addiction medicine and pain management ***DOCUMENT*** Chou, R, Fanciullo, G, Fine, P, et. al. Opioid Treatment Guidelines: Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: an update of Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. The Journal of Pain. 2009 Feb;10(2):113-130. Assessment ◦ ◦ ◦ Tools Available: Webster's Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) DIRE Tool Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients in Pain (SOAPP®) Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM ) Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ) Screening Tool for Addiction Risk (STAR) Screening Instrument for Substance Abuse Potential (SISAP) ◦ Pain Medicine Questionnaire (PMQ) ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ TM www.icsi.org Assessment and Management of Acute Pain guidelines and Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain Guidelines. Fifth Edition, November 2011. Pseudoaddiction to Opioids: A) B) C) A drug seeking behavior occurring in patients who are receiving inadequate pain control State of adaptation in which exposure to a drug decreases its effect over time Characterized by behaviors that include impaired control over drug use and continuation despite harm to self or others Repeated Opioid Dose Escalations: When repeatedly occur, evaluate for potential causes: ◦ Assess for treatment control (pseudoaddiction?) ◦ Possible marker for substance abuse disorder or diversion Theoretically no maximum or ceiling ◦ High dose definition = >200mg po morphine/day AAP Opioid Consensus Panel Some studies suggest higher doses of opioids lead to: ◦ Hyperalgesia ◦ Neuroendocrinologic dysfunction ◦ Possible immune suppression Chou, R, Fanciullo, G, Fine, P, et. al. Opioid Treatment Guidelines: Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: an update of Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. The Journal of Pain. 2009 Feb;10(2):113-130. Weaning/Tapering Off Opioids: Institute when: ◦ ◦ ◦ Patient engages in serious or repeated aberrant drug-related behaviors or diversion Experience of intolerable side effects Making no progress towards meeting therapeutic goals Approaches to Weaning Opioid: ◦ ◦ ◦ Slow: 10% dose reduction per week Rapid: 25-50% reduction every few days Slower rate may help reduce unpleasant symptoms of opioid withdrawal Chou, R, Fanciullo, G, Fine, P, et. al. Opioid Treatment Guidelines: Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: an update of Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. The Journal of Pain. 2009 Feb;10(2):113-130. Diagnosing Addiction in Patients Taking Opioids: Evidence of compulsive drug use, characterized by: ◦ Unsanctioned dose escalation ◦ Continued dosing despite significant side effects ◦ Use to treat for symptoms not targeted by therapy ◦ Use during periods of no symptoms Evidence of one or more associated behaviors: ◦ Manipulation of MDs or medical system to obtain additional opioids ◦ Acquisition of drugs from other medical sources or non-medical sources ◦ Drug hoarding or sales ◦ Unapproved use of other drugs (alchohol or other) Hojsted, J, Sjogren, P. Addiction to Opioids in Chronic Pain Patients: A Literature Review. European Journal of Pain. 2007;11:490-518. Consider for patient not well known and/or higher risk of misuse Example of components of opioid agreement: ◦ Specified the conditions under which opioids would or would not be prescribed ◦ Patient responsibilities Only receive opioids from Dr. ________ Will not give medications to anyone else If my prescription runs out early for any reason; have to wait until next prescription is due. Example of an Opioid Management Agreement: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1 829426/figure/Fig1 Random urine drug screening performed if recommended by the physician to monitor adherence and possible use of illicit substances. Patients informed that the agreement would be discontinued if patient responsibilities were not met. Responsibilities of the physician and/or clinic staff included providing monthly prescriptions on the due date, monitoring the effects of therapy, and providing ongoing care. Patient signs agreement Pharmacies licensed by the MN Board of Pharmacy and other dispensing facilities are required to report the dispensing of controlled substances listed in the state’s Schedules II-IV. ◦ Data is submitted electronically. Patient controlled substance prescription history is available to prescribers and pharmacists Available 24/7, 365 days a year, with information such as: ◦ Quantity and dosage of controlled substance dispensed, ◦ Pharmacy that dispensed the prescription ◦ In some cases, the practitioner Assists in checking for potential drug interactions, patterns of misuse, potential diversion or abuse and generally to assist in determining the appropriateness in dispensing. For pharmacist access: http://pmp.pharmacy.state.mn.us/pharmacist-rxsentryaccess-form.html Rational Use 1. Reassure patients prescribed opioids or benzos are taking as directed, evidenced by positive results 2. Make sure not being misused Stockpiling or selling to unauthorized others Evidenced by negative results 3. Detect presence of illicit non-prescribed drugs Heroin, cocaine, non-prescribed opioids, etc. Tenore, P. Advanced Urine Toxicology Testing. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 2010;29:436448. Two types of tests used: 1. Immunoassay ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Classify drug as present or absent Any response above the cutoff is deemed positive Any response below the cutoff is negative Subject to cross-reactivity Some detect specific drugs, while others classes, i.e. opioids Gourly D, Helt H, Yale C. Urine Drug Testing in Clinical Practice: The Art and Science of Patient Care. Stanford, CT: California Academy of Family Physicians, PharmaCom Group, Inc; 2010. Immunoassay Pearls: Human urine has a creatinine concentration greater than 20 mg/dL. In the clinical setting it is important that 300 ng/mL or less be used for initial screening of opiates (Food stuff and poppy seed can make +); Confirm with laboratory test Opiate Class; lower sensitivity to hydromorphone , hydrocodone, oxycodone , oxymorphone, fentanyl, meperidine, and methadone Gourly D, Helt H, Yale C. Urine Drug Testing in Clinical Practice: The Art and Science of Patient Care. Stanford, CT: California Academy of Family Physicians, PharmaCom Group, Inc; 2010. Gourly D, Helt H, Yale C. Urine Drug Testing in Clinical Practice: The Art and Science of Patient Care. Stanford, CT: California Academy of Family Physicians, PharmaCom Group, Inc; 2010. Immunoassay Pearls (continued): Amphetamine/methamphetamine are highly crossreactive ◦ may detect other ephedrine and pseudoephedrine ◦ Further testing may be required by a more specific method, i.e. GC Opiate class: morphine and codeine Ability of opiate immunoassays to detect semisynthetic/ synthetic opioids varies among assays because of differing cross-reactivity patterns. Specific immunoassay tests for some semisynthetic/ synthetic opioids may be available (eg, oxycodone, methadone). Gourly D, Helt H, Yale C. Urine Drug Testing in Clinical Practice: The Art and Science of Patient Care . Stanford, CT: California Academy of Family Physicians, PharmaCom Group, Inc; 2010. 2. GC/MS (Laboratory Testing) Generally, a more definitive laboratory-based procedure Identify specific drugs; may be needed: (1) Specifically confirm the presence of a given drug; i.e. morphine is the opiate causing the + IA response (2) to identify drugs not included in an immunoassay test (3) when results are contested. Gourly D, Helt H, Yale C. Urine Drug Testing in Clinical Practice: The Art and Science of Patient Care. Stanford, CT: California Academy of Family Physicians, PharmaCom Group, Inc; 2010. Examples of cross-reacting compounds for certain immunoassays Interfering drug Quinolone antibiotics Trazodone Venlafaxine Quetiapine Efavirenz Promethazine Dextromethorphan Proton pump inhibitors Immunoassay affected Opiates Fentanyl Phencyclidine Methadone THC Amphetamine Phencyclidine THC Gourly D, Helt H, Yale C. Urine Drug Testing in Clinical Practice: The Art and Science of Patient Care. Stanford, CT: California Academy of Family Physicians, PharmaCom Group, Inc; 2010. Approximate windows of detection of drugs in urine Detection time Drug in urine Amphetamines Up to 3 days THC (Single use) 1 to 3 days (Chronic use) Up to 30 days Cocaine use 2 to 4 days Opiates (morphine, codeine) 2 to 3 days Methadone Up to 3 days EDDP (methadone metabolite) Up to 6 days Benzodiazepines Days to weeks Gourly D, Helt H, Yale C. Urine Drug Testing in Clinical Practice: The Art and Science of Patient Care. Stanford, CT: California Academy of Family Physicians, PharmaCom Group, Inc; 2010. Consult lab regarding anything unexpected Schedule appointment to discuss with patient ◦ Be positive and supportive Use to strengthen the healthcare professional-patient relationship Support positive behavior change FDA recommendations for disposal ◦ Locate medication take back program in community ◦ Example: Dakota County Sherriff’s Office has a drop box at the Burnseville Police Department and the Hastings Sherriff’s Office where people can drop off their prescriptions anonymously ◦ Many drop box locations in Hennepin county: http://www.hennepin.us/medicine Hennepin County Drop Box Example: http://www.hennepin.us/medicine FDA recommendations for disposal ◦ If no medication take back program Mix medications with unpalatable substance Place mixture in container such as sealed bag Throw container in household trash ◦ Exception: List of meds recommended to dispose by flushing http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/B uyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/Safe DisposalofMedicines/ucm186187.htm FDA recommended for flushing (examples): ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Fentanyl (SL tabs, film, lozenge, patch) Morphine Meperidine Hydromorphone Methadone Oxycodone Tapentadol Others listed on FDA updated website: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/Buyin gUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDispos alofMedicines/ucm186187.htm Federal controlled substance laws and rules prohibit a pharmacy from receiving controlled substances from anyone who is not a registrant of the US DEA. Pharmacists are not allowed to accept controlled substances from patients or members of the public. Assessment of pain is key every time you see a patient Opioids can be part of a comprehensive pain management approach for a non-cancer chronic pain patient; document all assessment and communication regarding opioids each office visit Ensure pain is being treated appropriately with a multimodal approach using the best medications and therapy for the individual patient Utilize expertise of other non-pharmacy professionals for additional therapy to synergistically treat pain Guidelines: Assessment and management of chronic pain. 2005 Nov (revised 2011 Nov). NGC:008967 Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement - Nonprofit Organization. Adult acute and subacute low back pain. 1994 Jun (revised 2012 Jan). NGC:008959 Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement - Nonprofit Organization Diagnosis and treatment of headache. 1998 Aug (revised 2011 Jan). NGC:008263 Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement - Nonprofit Organization Pain (chronic). 2003 (revised 13 May 2011). NGC:008519 Work Loss Data Institute - For Profit Organization. Guideline for the evidence-informed primary care management of low back pain. 2009 Mar. [NGC Update Pending] NGC:007704 Institute of Health Economics - Nonprofit Research Organization; Toward Optimized Practice State/Local Government Agency [Non-U.S.]. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. 2009 Feb. NGC:007852 American Academy of Pain Medicine - Professional Association; American Pain Society. Other References: 1) American Pain Society (APS). Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain, 6th edition. 2008. Glenview, IL 60025. 2) Anderson AV, Fine PG, Fishman SM. Opioid Prescribing: Clinical Tools and Risk Management Strategies. Sonora, CA: American Academy of Pain Management; December 31, 2009. http://www.state.mn.us/mn/externalDocs/BMP/New_Article_on_Pain_Management_020110034248_m onograph_dec_07_final.pdf. Accessed June 2012 3) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492. 4) Chou, R, Fanciullo, G, Fine, P, et. al. Opioid Treatment Guidelines: Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: an update of Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. The Journal of Pain. 2009 Feb;10(2):113-130. 5) Clark LG, Upshur CC. Family medicine physicians’ views of how to improve chronic pain management. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(5):479-482. 6) Evans L, Whitham JA, Trotter DR, Filtz KR. An evaluation of family medicine residents’ attitudes before and after a PCMH innovation for patients with chronic pain. Fam Med. 2011;43(10):702-711 7) Fine, G. Opioid Rotation: Definition and Indications. Pain Management Today eNewsletter series. American Pain Foundation. , Quadrant HealthCom Inc. ; 2010: (1): 9. http://newsletter.qhc.com/JFP/JFP_pain032411.htm 8) Gourly D, Helt H, Yale C. Urine Drug Testing in Clinical Practice: The Art and Science of Patient Care. Stanford, CT: California Academy of Family Physicians, PharmaCom Group, Inc; 2010. 9) Hojsted, J, Sjogren, P. Addiction to Opioids in Chronic Pain Patients: A Literature Review. European Journal of Pain. 2007;11:490-518. 10) Katz NP. Opioid Prescribing Toolkit. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. 11) Leverence RR, Williams RL, Potter M, et al. Chronic non-cancer pain: a siren for primary care—a report from the PRImary care MultiEthnic Network (PRIME Net). J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(5):551561. 12) Matthias MS, Parpart AL, Nyland KA, et al. The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain care: physicians’ perspectives. Pain Med. 2010;11(11):1688-1697 13) The Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines: management of opioid therapy for chronic pain. 2010. Version 2.0-2010. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/COT_312_Full-er.pdf. Accessed June 2012. 14) Patanwala, et. al. Comparison of Opioid Requirements and Analgesic Response in Opioid-Tolerant versus Opioid-Naïve Patients After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28(12):1453-1460 ne 2012. 15) Pizzo PA, Clark NM, Carter-Pokras O, et al; Institute of Medicine Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011:119-120. 16) Project Lazarus. Community-based overdose prevention from North Carolina and the Community Care Chronic Pain Initiative. http://www.projectlazarus.org. Accessed Ju 17) Reuben, S. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1215-1224. Burns, A. J Orthop Surgery. 2006; 14(3):280-3. 18) Tenore, P. Advanced Urine Toxicology Testing. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 2010;29:436-448. 19) Upshur CC, Luckmann RS, Savageau JA. Primary care provider concerns about management of chronic pain in community clinic populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):652-655. 20) Wismer B, Amann T, Diaz R, et al. Adapting Your Practice: Recommendations for the Care of Homeless Adults with Chronic Non-Malignant Pain. Nashville, TN: Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network, National Healthcare for the Homeless Council, Inc; 2011.