Lecture 10 Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1st hour), The School for

advertisement

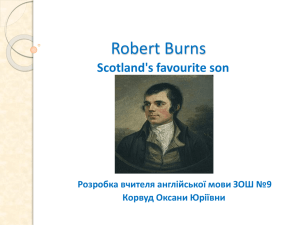

Lecture 10 Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1st hour), The School for Scandal, Robert Burns (2nd hour) • • 18th Century English Drama: The English drama of the 18th century does not reach the same high level as its novel. One of the main reasons is that the Licensing Act of 1737 which drove Fielding out of the theatre restricted the freedom of expression by dramatists. The stage, losing its power as a serious criticism of social life, declined at the same time in its splendour and magnificence as a lofty entertainment, The greatest problem in 18th century English drama is not that of a playwright, but that of a player, David Garrick (1717-1779 ), who created a school of acting that was “ natural” as compared to the more formalized gestures and poses of the past. Garrick was a great popularizer of Shakespeare and in 1769 started the Shakespeare Jubilee at Stratford-on-Avon, an event that established Shakespeare as the national bard of England and Stratford as a permanent tourist attraction.The English drama experienced a brief flowering in the second half of the 18th century for the comedies of Sheridan and Goldsmith. • Life and career • Born: 30-Oct-1751 Birthplace: Dublin, Ireland Died: 7-Jul-1816 Location of death: London, England Cause of death: unspecified Remains: Buried, Westminster Abbey, London, England • Occupation: Playwright, Politician • Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816), the most important English playwright of the 18th century, was born in Dublin. His father was an actor and his mother a novelist: Richard went to study at Harrow in 1762. His mother died when he was 15. In a few years his father brought the family to England settled in Bath. The young man tried Iris hand at literature and wrote some minor works in collaboration with a friend. In 1772 Sheridan fell in love and eloped with Elizabeth Ann Linley, a beautiful singer, after fighting two duels with his rival. After marriage, the Sheridans lived happily in a country cottage. In 1775, Sheridan’s first comedy “The Rivals" was produced at Covent Garden Theatre in London. After it, he wrote several other plays, and “The School for Scandal” (1777) is his masterpiece. In 1776 he became the manager of Drury Lane Theatre. • His first comedy, The Rivals, was produced at Covent Garden on the 17th January 1775. It is said to have been not so favorably received on its first night, owing to its length and to the bad playing of the part of Sir Lucius O'Trigger. But the defects were remedied before the second performance, which was deferred to the 28th of the month, and the piece at once took that place on the stage which it has never lost. His second piece, St. Patrick's Day, or the Scheming Lieutenant, a lively farce, was written for the benefit performance (2nd of May 1775) of Lawrence Clinch, who had succeeded as Sir Lucius. In November 1775, with the assistance of his father-in-law, he produced the comic opera of The Duenna, which was played 75 times at Covent Garden during that season. • School for Scandal opened at the Drury Lane Theatre in London, England, in May of 1777. It was an enormous success. Reviews heralded the play as a "real comedy'' that would supplant the sentimental dramas that had filled the stage in the previous years. While wildly popular in the eighteenth century, the play has not been as successful with contemporary audiences. • One significant problem is the anti-Semitism that runs throughout the play. • “The School for Scandal": • “The School for Scandal” has been called a great comedy of manners. It gives a brilliant portrayal and a biting satire of English high society. In the play, the author contrasts two brothers, Charles Surface and Joseph Surface. Charles seems a reckless • prodigal from all outward appearances but he is frank honest and good-hearted. Joseph seems to be pious, always declaring noble feelings uttering moral speeches and appearing to be a man of honour. But behind his mask he is a hypocrite, a backbiter and a seducer of his friend’s wife. • Charles is in love with Maria. Sir Peter Teazle’s ward, and his affection is returned. Meanwhile, Sir Peter, an elderly gentleman. has married a very young wife. Lady Teazle, coming from 1.he countryside, becomes attracted by the fashionable life in London and leis her in for love affairs beyond the bounds of marriage. So they are at odds with each other. Moreover, the ladies and gentlemen who gather at Lady Sneerwell’s, under her encouragement, put about scandalous stories in high society. These scandal-mongers, who "strike a character dead at every word," make life troublesome for all people. Now Lady Sneerwell, in love with Charles, instigates Joseph to pursue Maria, and Joseph, while making advances to Maria, secretly tries to seduce Lady Teazle. Sir Peter, owing to the fabrications of Lady Sneerwell and Joseph Surface, believes Charles to be the person flirting with his young wife. One day, Lady Teazle foolishly pays Joseph a visit in his own room. He is on the point of corrupting her when Sir Peter arrives unexpectedly. Lady Teazle is forced to hide behind a screen. Then quite unexpectedly, Charles turns up and Sir Peter in turn has to take cover. The climax comes when Charles knocks over the screen and reveal Lady TeazIe. • Thus Sir Peter finds out that it is not Charles but Joseph who has been carrying on an intrigue with his wife. Then it is learned that Sir Oliver Surface, the uncle of Charles and Joseph, has returned to England from the East. Sir Oliver is determined to ascertain for himself the truth about his two nephews. He visits Charles in the guise of a usurer. Charles sells all the family portraits to him but refuses to part with him-- that of his uncle’s. Then Sir Oliver appears before Joseph in the character of a poor relative asking for help, which Joseph refuses to give on the pretext that the “poverty” is brought on by the stinginess of his uncle. This completes the exposure of Joseph. Charles marries Maria. and Sir Peter is reconciled to Lady Teazle. This play. repudiating the high society for its vast, greed and hypocrisy, has been regarded as the best English comedy since Shakespeare. • Robert Burns (1759-1796) • 1. Life and career • Blake, deeply romantic as he is by nature, virtually stands by himself, apart from any movement or group, and the same is equally true of the somewhat earlier lyrist in whom eighteenth century poetry culminates, namely Robert Burns. Burns, the oldest of the seven children of two sturdy Scotch peasants of the best type, was born in 1759 in Ayrshire, just beyond the northwest border of England. In spite of extreme poverty, the father joined with some of his neighbors in securing the services of a teacher for their children, and the household possessed a few good books, including Shakespeare and Pope, whose influence on the future poet was great. His mother had familiarized him from the beginning with the songs and ballads of which the country was full, and though he is said at first to have had so little ear for music that he could scarcely distinguish one tune from another, he soon began to compose songs (words) of his own as he followed the plough. • At the age of twenty-seven, abandoning the hope which he had already begun to cherish of becoming the national poet of Scotland, he had determined in despair to emigrate to Jamaica to become an overseer on a plantation. (That this chief poet of democracy, the author of 'A Man's a Man for a' That,' could have planned to become a slave-driver suggests how closely the most genuine human sympathies are limited by habit and circumstances.) To secure the money for his voyage Burns had published his poems in a little volume. This won instantaneous and universal popularity, and Burns, turning back at the last moment, responded to the suggestion of some of the great people of Edinburgh that he should come to that city and see what could be done for him. • Burns' place among poets is perfectly clear. It is chiefly that of a song-writer, perhaps the greatest songwriter of the world. At work in the fields or in his garret or kitchen after the long day's work was done, he composed songs because he could not help it, because his emotion was irresistibly stirred by the beauty and life of the birds and flowers, the snatch of a melody which kept running through his mind, or the memory of the girl with whom he had last talked. And his feelings expressed themselves with spontaneous simplicity, genuineness, and ease. He is a thoroughly romantic poet, though wholly by the grace of nature, not at all from any conscious intention--he wrote as the inspiration moved him, not in accordance with any theory of art. The range of his subjects and emotions is nearly or quite complete--love; comradeship; married affection, as in 'John Anderson, My Jo'; reflective sentiment; feeling for nature; sympathy with animals; vigorous patriotism, as in 'Scots Wha Hae' (and Burns did much to revive the feeling of Scots for Scotland); deep tragedy and pathos; instinctive happiness; delightful humor; and the others. • My Heart's in the Highlands • My heart's in the Highlands, my heart is not here; My heart's in the Highlands a-chasing the deer; Chasing the wild-deer, and following the roe, My heart's in the Highlands wherever I go. • Farewell to the Highlands, farewell to the North, The birth-place of Valour, the country of Worth; Wherever I wander, wherever I rove, The hills of the Highlands for ever I love. Farewell to the mountains high covered with snow! Farewell to the straths and green valleys below! Farewell to the forests and wild-hanging woods! Farewell to the torrents and loud-pouring floods! • My heart's in the Highlands, my heart is not here; My heart's in the Highlands a-chasing the deer; Chasing the wild-deer, and following the roe, My heart's in the Highlands wherever I go. • A Red, Red Rose • O, my luve’s like a red, red rose, That's newly sprung in June; Oh my luve’s like the melodie That's sweetly play'd in tune. As fair art thou, my bonnie lass, So deep in luve am I; And I will luve thee still, my dear, Till a' the seas gang dry. • Till a' the seas gang dry, my dear, And the rocks melt wi' the sun; And I will luve thee still, my dear, While the sands o' life shall run. • And fare thee weel, my only luve! And fare thee weel a while! And I will come again, my luve, Tho' it were ten thousand mile! • Auld Lang Syne • Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind ? Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and auld lang syne ? • • • • • CHORUS: For auld lang syne, my dear, for auld lang syne, we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet, for auld lang syne. • And surely ye’ll be your pint-stoup ! And surely I’ll be mine ! And we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet, for auld lang syne. • CHORUS • We twa hae run about the braes, and pou’d the gowans fine ; But we’ve wander’d mony a weary fit, sin’ auld lang syne. • CHORUS • We twa hae paidl’d in the burn, frae morning sun till dine ; But seas between us braid hae roar’d sin’ auld lang syne. • CHORUS • And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere ! And gives a hand o’ thine ! And we’ll tak a right guid-willie-waught, for auld lang syne.