What is attitude?

advertisement

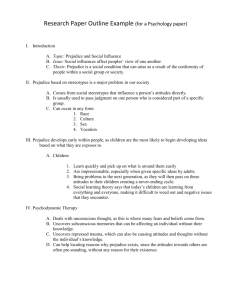

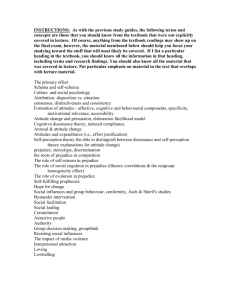

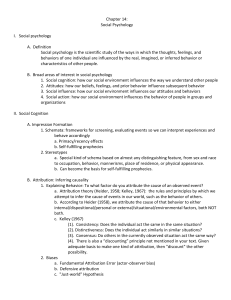

UNIT 2 PSYCHOLOGY – SELF AND OTHERS Area of study 1: Interpersonal and group behaviour Area of study 2: Intelligence and personality CHAPTER SIX – INTERPERSONAL AND GROUP BEHAVIOUR ATTITUDE OBTAINING DATA Measuring attitudes Questionnaires Self-report Rating scale Observation Likert scale Interview COMPONENTS NEGATIVE EMOTIONS Prejudice Discrimination Cognitive component (thoughts) Affective component (emotions) Behavioural component (actions) Sexism Racism Ageism CHANGES IN ATTITUDES Cognitive interventions Reduction in prejudice Equality Mutual interdependence Superordinate goals Sustained contact Attitudes and influence This chapter deals with the relationships between individuals, within groups and the influences of groups on attitudes formation. It is important to notice that when behaviour is measured, several attitudes can be influential and interest does not especially have to be the most important motivator for behaviour. A change in attitude takes time; it needs to be facilitated and must employ strategies that will ensure permanency. What is attitude? Attitudes are intimately woven into our actions and views of the world. Our tastes, friendships, votes, preferences and goals are all influenced by our attitudes. An attitude is a learnt idea about ourselves or others, or objects and experiences. Attitudes cause a person to respond in a positive or negative way. The tri-component model proposes that there are three components that contribute to attitude formation: 1. Feelings (the affective component) 2. Actions (the behavioural component) 3. Thoughts (the cognitive component) Attitudes summarise your evaluation of objects. As attitudes are learned, the effects of experience, personal influence and exposure to the media need to be considered in determining the reason for the formulation of the attitude. The tri-component attitude model is applicable to many situations, such as examining factors that influence customers behaviour, determining what affects the choice of destination when you travel and identifying your choice in music. It does have limitations and it does not provide answers, but insights. The affective component consists of feelings towards the object or person- that is, how you feel. The behavioural component refers to a person’s actions towards various people, objects or institutions- that is, what you do. The cognitive component of an attitude is what a person thinks about an object or person – that is, why you believe this. This is known as the ABC of attitudes. FOR EXAMPLE: Your attitude towards owning guns. You will have an emotional response; finding them attractive and useful or threatening and destructive (THE AFFECT COMPONENT) You will have a tendency to agree or disagree with gun ownership (THE BEHAVIOURAL COMPONENT) You will have thoughts about whether gun control would affect rates of crime or violence (THE COGNITIVE COMPONENT) Attitude formation Sometimes, attitudes come from direct contact (personal experience) with the object of the attitude Such as opposing pollution when a nearby factory blackens and ruins your favourite white shirt hanging on your clotheslines. Attitudes are also learnt through interaction with others – that is, through discussion with people holding a particular attitude. Child rearing (parental values, beliefs and practices applied while caring for a child) also affects attitudes. Many of our attitudes are influenced by our group membership – that is, our association with the people with whom we share common characteristics. Attitudes are also influenced and skilfully manipulated by the media (magazines, television, radio), which reaches large audiences. 99% of Australian homes have a TV turned on for an average of over 7 hours a day. The information that is channelled into homes has a powerful impact. A steady diet of TV violence leads some people to develop a mean worldview, causing them to regard the world as a dangerous and threatening place (Heath & Gilbert, 1996) Chance conditioning Some attitudes are simply formed through chance conditioning, or learning that takes place by chance or coincidence (Olson & Zanna, 1993) People often develop strong attitudes towards cities, restaurants or parts of the country on the basis of one or two unusually good or bad experiences. Attitude change Although attitudes are relatively stable, they do change. Some attitude change can be understood in terms of a reference group. A reference group can be any group a person identifies with and uses as a standard for social comparison. It is not necessary to have face-to-face contact with other people for them to serve as a reference group. It depends instead on whom you identify with or whose attitudes and values you care about. Psychologists refer to persuasion as any deliberate attempt to change attitudes or beliefs through information and arguments. Businesses, politicians and others who seek to persuade us obviously believe that attitudes can be changed. BILLIONS of dollars are spent yearly on advertising in Australia. Persuasion can range from the daily blitz of media commercials to personal discussion among friends. Consumer psychology is an applied field that focuses on how consumers behave. It would appear that people give little thought to the act of purchasing a product but, in fact, consumer behaviour consists of deciding to spend, selecting a brand, shopping, making a purchase and evaluating the product in use. At each step, advertising, packaging and a host of other factors affect our attitudes and, ultimately, our behaviour. Market research is often done. It is a type of public opinion polling, in which people are asked to give their personal impressions of products, services and advertising. A brand image is the mental ‘picture’ that consumers have of a product, especially with regard to its emotional meaning. BMW (high status), V8 Holden (power) and Volvo (conservative). Brand images tend to direct buying behaviour, and they may help explain why many people purchase products for their labels as much as for their performance. Cognitive dissonance theory What happens if people act in ways that are inconsistent with their attitudes or self-image? The contradiction makes them uncomfortable. Such discomfort can motivate people to make their thoughts or attitudes agree with their actions. Cognitive dissonance (‘cognitions’ are thoughts; ‘dissonance’ means clashing.) The influential theory of cognitive dissonance states that contradicting or clashing thoughts cause discomfort – that is, we have a need for consistency in our thoughts, perceptions and images of ourselves. Prejudice – attitudes that hurt Not all attitudes towards people are positive ones. Some are negative and form the basis of prejudice. What is prejudice? Love and friendship bind people together. Prejudice, which is marked by suspicion, fear or hatred, has the opposite effect. In this context, prejudice is a negative emotional attitude held towards members of a specific social group. Prejudice can exist in almost any situation. Stereotypes Most people publicly support policies of quality and fairness. Many people still have lingering biases and negative images of minority groups or women. Patricia Devine, a social psychologist, has shown that making the decision to stop being prejudiced does not immediately eliminate prejudiced thoughts and feelings. Unprejudiced people may continue to respond in an emotionally negative way to members of minority groups. Stereotypes are oversimplifies images of people who belong to a particular group. It places people into categories, almost always causing them to appear more similar than they really are. An example of stereotyping: ‘People over 65 years of age are old and senile’. Grouping them into ‘us’ and ‘them’ categories. They are mainly an expression of a negative attitude towards a group that is used to maintain control over other people. When people have been stereotyped, the easiest thing for them to do is to abide by others’ expectations – even if the expectations are demeaning. Being forced into a small, distorted social ‘box’ by stereotyping is limiting and insulting. Stereotypes rob people of their individuality. Without stereotypes, there would be far less hate, prejudice, exclusion and conflict. Reducing prejudice Attitudes and behaviours can change if we genuinely want them to. Become aware of the factors that work towards reducing prejudice. These factors include: Inter-group contact Sustained contact Superordinate goals Mutual interdependence Equality Inter-group contact One way to reduce prejudice is to increase the intergroup contact between the people who hold the stereotype and those who are the target of the stereotype. Stereotypes can be broken down and replaced with more positive attitudes when the inter-group contact is maintained over a period of time, when meeting the goals for each group requires mutual independence, and when equality exists through equal-status participation. One of the effects of inter-group contact is it positively impacts on the cognitive (belief) component of an attitude. It makes people aware that members of various racial and ethnic groups share the same goals, ambitions, feelings and frustrations as they do, and this has a positive effect on attitudes. The Australian Administrative Appeals Tribunal is committed to creating a working environment that values and utilises the contribution of its employees and members from diverse backgrounds and experiences. Sustained contact Sustained contact means that there should be prolonged and involved cooperative activity rather than a casual and purposelessness contact. Individuals who work together to achieve a shared goal for extended periods of time have an opportunity to get to know the reality of the other groups. Superordinate goals Shared goals, which groups or individuals cannot achieve alone or without the other person or group As members of the groups are forced to cooperate, this can lead to hostilities and prejudices lessening or even disappearing. Cooperation and shared goals seem to help reduce conflict by encouraging people in opposing groups to see themselves as members of a single, larger group. ‘We are all in the same boat’ effect on perceptions of group membership. In order to reduce or remove prejudice, it is important that the common goal is achieved. Mutual interdependence Another inter-group contact goal that is effective in reducing prejudice is mutual interdependence. People must depend on one another to meet each persons goals. When each person’s need are linked to those of others in the group, cooperation is encouraged. Equality (equal-status contact) Equality involves social interaction that occurs at the same level, without obvious differences in power or status. Much evidence suggests that equal-status contact does lesson prejudice. Benefits only occur when personal contact is cooperative and at an equal level. Cognitive interventions 1. 2. 3. 4. Individuals can guard against becoming prejudiced by using cognitive interventions Cognitive interventions are learned skills and behaviours that we can use to combat prejudice. They help us to: Be less susceptible to the manipulation of others Analyse and understand our own attitudes and those of others Predict the behaviour of others Promote pleasant interactions The following seven cognitive interventions may be helpful to overcome prejudice. Beware of stereotypes. Stereotyping is used to control others and make the social world seem more manageable. A good way to reduce stereotyping is to get to know individuals from various racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Seek individuating information. One of the best antidotes for stereotypes is individuating information, or information that helps us see a person as an individual, rather than as a member of a group. Do not fall into just-world beliefs. This is the belief that people generally get what they deserve. This can lead us to assume that minority groups would not be in such positions if they were not inferior in some way. A just-world belief can result in discrimination, which can lead to minority groups occupying lower socioeconomic positions in society. Be aware of self-filling prophecies. A self-fulfilling prophecy is an expectation that prompts people to act in ways that make the expectation come true. People tend to act in accordance with the behaviour expected by others. When you meet someone different from yourself, you may treat them in a way that is consistent with your stereotypes. If the other person is influenced by your behaviour, they may act in ways that seem to match your stereotype, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy and reinforcing your belief in the stereotype. Remember: different does not mean inferior: What can be avoided is unnecessary social competition (rivalry among groups, each of which regards itself as superior to others). The concept of social competition involved some individuals seeking to enhance their self-esteem by identifying with a group. An example is the school environment. Because of social competition, groups tend to view themselves as better than their rivals, so, if we don’t want to promote prejudice we must remember to avoid unnecessary social competition. Look for commonalities. Competition and individual effort can have a negative impact. In some situations competition and a desire to win can also encourage the desire to demean, defeat and dominate those we are competing against. Example: physical intimidation and verbal abuse on the sports field. When we look for commonalities, or things we have in common with others who are different from us, we cooperate with them, and we tend to share their joys and suffer when they are in distress. Develop cultural awareness. Living in a multicultural society such as Australia means becoming more informed about other groups who are different to us. Cultural awareness is one way to combat racism. The more exposure an individual has to different cultures, the better able they are to understand the differences. Discrimination Prejudice leads to discrimination or the unequal treatment of people who should have the same rights as others. Discrimination frequently prevents people from doing things they should have the opportunity to do such as getting a job or buying a house. In 1977 the Anti-discrimination Act 1977 (NSW) came into force to eliminate prejudices such as racism and sexism that had become institutionalised. The Act makes it unlawful to discriminate on grounds of sex, race and marital status in the areas of employment, accommodation, goods and services, and education. In all cases the individual becomes disempowered and less able to achieve the rights and opportunities afforded to others. Sexism Refers to an attitude that is a mixture of negative thoughts and stereotypes, and feelings of fear, envy or hostility, that results in discrimination based on gender. Racism Refers to an attitude that is a mixture of negative thoughts and stereotypes, and feelings of fear, envy or hostility, that results in discrimination based on race. A research study suggested a substantive degree of racism exists in Australia. Ageism It is an attitude that is mixture of negative thoughts and stereotypes, and feelings of fear, envy or hostility, that results in discrimination based on age. The systematic stereotyping against other people termed ‘ageism’ often goes unnoticed and unchallenged. THE BASE OF PREJUDICE Scapegoating How do prejudices develop? One major theory suggests that prejudice is a form of scapegoating (blaming a person or a group for the actions of others or for conditions not of their making). Scapegoating is a type of displaced aggression in which hostilities triggered by frustration are redirected at ‘safe’ targets. Example: when immigrants are blamed for taking jobs and contributing to unemployment for Australians. Direct experience The development of prejudice can be traced to direct experience with members of the rejected group. A child who is repeatedly bullied by members of a particular racial or ethnic group might develop a lifelong dislike for all members of that group. The tragedy is that, once prejudices are established, they prevent us from accepting more positive experiences that could reverse the damage Personal and group prejudice Psychologist Gordon Allport (1958) concluded that there are two important sources of prejudice: personal and group prejudices. Personal prejudice: occurs when members of another racial or ethnic group are perceived as a threat to one’s own interests. Group prejudice: occurs when a person conforms to group norms. This does not necessarily imply that the individual agrees with the views of the group. Long-term membership of a group can cause attitudinal change to the point where it becomes a real belief and not one just for the purposes of group identity. The prejudiced personality People with authoritarian personalities – usually rigid, inhabited and likely to oversimplify things – are more likely to consider their own ethnic or racial group superior to others. Authoritarians are more likely to be prejudiced against almost everyone who is different, including homosexuals. Social and cultural differences Prejudices such as sexism, racism and ageism have become institutionalised; that is, they are reflected in government policy, in schools and so on. This can make it a long process of change to reduce the discrimination experienced by affected individuals and groups. Inter-group contact provides the opportunity for discussion and to find commonalities that exist between cultures. SEXISM Women have suffered historically due to their low positions of power compared with men in employment, government and business. Today in Western culture, women are valued more positively; yet, globally, women still suffer enormous prejudice. In Western culture, four dominant female stereotypes contributing to prejudice can be identified: housewife, sexy women, career women and feminist/athlete/lesbian (Klasen, 1994) Some occupations are labelled ‘women’s work’ and are therefore less valued. Men take home more discretionary pay than women – including overaward payments, bonus payments, profit sharing, service increments and commissions – mostly because of the concentration of women in jobs that do not attract such payments. Much of this can be blamed on society’s expectation of a woman’s working role. Women still carry an inordinate amount of family responsibility, which impacts on earnings because they may not be able to work full-time, or may miss training courses and other career development opportunities. The mass media portrays women as beautiful as well as domestic goddesses. Men are shown as tough, competitive and business-savvy. This tendency also contributes to sexism and therefore to prejudice, by sending the message that women are more important for their physical characteristics than their intellectual capacity, thus perpetuating gender prejudice in our society. ‘Social hierarchy’ allows those with higher power to determine the rights and privileges of others and leads to situations of inequity, discontent and discrimination. Sexism can affect men as well as women. The family policy of governments and employers can affect men in terms of their ability to balance work and family commitments. RACISM Prejudice and discrimination on the basis of cultural differences have been responsible for many wars and horrible acts of violence over the centuries. However, racism is not always so obviously or overtly expressed. Vaughan and Hogg (2002) refer to a new form of racism known as modern or subtle racism. In Australia, the physical, material and spiritual plight, as well as the education and employment prospects, of Indigenous Australians have not improved significantly in recent times, even though overt racism has diminished. A way of reducing conflict between cultural groups due to beliefs or misconceptions is through inter-group contact. This has been promoted in the concept of multiculturalism giving equal status to different ethnic, racial and cultural groups. In providing this equal status, multiculturalism recognises and accepts human diversity. Police work is one area where it is dangerous to harbour prejudices against different races or cultures. AGEISM Ageism is broadly defined as any prejudice or discrimination against or in favour of an age group. It is an attitude that is a mixture of negative thoughts and stereotypes, and feelings of fear, envy or hostility, that results in discrimination. Birthday cards make fun about the advance of age, the images of the aged on TV are rarely positive, and we use many colloquialisms to describe old people. Aged people in some cultures are respected as wise and very important people. In Japan, ageing is seen as positive and greater age brings more status and respect. However, in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and Britain, many elderly people are treated as burdens on society and without the same basic human rights as younger citizens. They are often forced to live on a smaller income or pension and the government has neglected to sufficiently monitor and regulate the agedcare industry. As our community ages, fewer and fewer Australian families will be able to cope without using an aged-care facility. Businesses frequently reinforce ageist stereotypes by not hiring or promoting older workers. Many professionals and human service professionals perpetuate ageism. People subjected to prejudice and discrimination tend to adopt the dominant group’s negative image and to behave in ways that conform to that negative image. The dominant group’s negative image typically included a set of behavioural expectations or prescriptions that define what a person is to do and not to do. For example, aged people are expected to be asexual, intellectually rigid, unproductive, forgetful, happy, enjoying their retirement, and also invisible, passive and uncomplaining. MEASURING ATTITUDES Observation of behaviour Attitudes can be measured several ways. One way of doing this is through observation of behaviour. Observational studies are an effective way to determine a person’s attitude towards an object, person or experience. This information can then be used to determine the behavioural component of their attitude. Qualitative data Qualitative data have to be interpreted in order to formulate a conclusion to research. You cannot statistically analyse qualitative data. We can observe and record a person’s behaviour by describing it. Self-reports Individuals are simply asked to freely express attitudes towards a particular object, person or experience. The thoughts that a person expresses can be recorded and described as subjective data. Subjective data comprise information that reflects the individual’s perceptions and cannot be attributed to other individuals. Examples are open-ended questions, fixed-response questions, indirect questions or rating on a multi-point scale such as a Likert scale. Open-ended interviews Individuals are asked to comment freely and without limitation on their attitude towards a particular issue. Interviews often produce a large amount of data for analysis – this can be both and advantage and disadvantage. A large amount of descriptive data can give very specific, interesting and useful information about people’s attitudes, but sifting through it can be time-consuming. People might find it difficult to explain their thoughts and feelings, especially when put on the spot. Fixed-response questions Restrict the participant’s responses to interview questions to only a limited choice of answers. For example: ‘Do you believe that teachers should be able to strike at any time for a pay rise?’, participants could be given these options: Yes/No/Undecided. Indirect questioning Subjects are asked to write down the adjectives that they would use to describe their attitude to a person, object or experience. The objectives are then analysed to determine whether the person has a positive or negative evaluation of, or attitude towards, the issue. Quantitative data: Likert scales Information collected in numerical form, which can then be used to statistically describe a characteristic, behaviour or attitude. The Likert scale is one of the most common methods of measurement of quantitative data. Likert scales consist of statements expressing various possible views on an issue. Ranking their responses from strongly agree to agree to undecided to disagree to strongly disagree. A person’s attitude is measured when they indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with each statement about the issue. A person can be rated for overall acceptance or rejection of a particular issue. When creating a Likert scale, you should try to have an equal number of statements that represent a positive attitude and negative attitude to the issue.