Chapter 1

advertisement

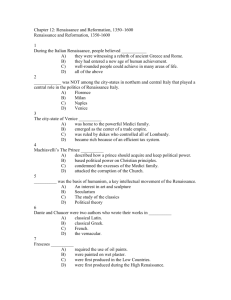

Chapter 13 European Society in the Age of the Renaissance, 1350–1550 A Bank Scene, Florence Originally a “bank” was just a counter; moneychangers who sat behind the counter became “bankers,” exchanging different currencies and holding deposits for merchants and businesspeople. In this scene from fifteenth-century Florence, the bank is covered with an imported Ottoman geometric rug, one of many imported luxury items handled by Florentine merchants. Prato, San Francesco/Scala/ArtResource, NY The Italian City-States, ca 1494 In the fifteenth century the Italian city-states represented great wealth and cultural sophistication. The political divisions of the peninsula invited foreign intervention. Uccello: Battle of San Romano Fascinated by perspective—the representation of spatial depth or distance on a flat surface—the Florentine artist Paolo Uccello (1397–1475) celebrated the Florentine victory over Siena (1432) in a painting with three scenes. Though a minor battle, it started Florence on the road to domination over smaller nearby states. The painting hung in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s bedroom. National Gallery,London/Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY Benvenuto Cellini: Saltcellar of Francis I (ca 1540) In gold and enamel, Cellini depicts the Roman sea god, Neptune with trident, or three-pronged spear), sitting beside a small boat-shaped container holding salt from the sea. Opposite him, a female figure personifying Earth guards pepper, which derives from a plant. Portrayed on the base are the four seasons and the times of day, symbolizing seasonal festivities and daily meal schedules. Classical figures portrayed with grace, poise, and elegance were common subjects in Renaissance art. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna/The Bridgeman Art Library Raphael: Portrait of Castiglione In this portrait by Raphael, the most sought-after portrait painter of the Renaissance, Castiglione is shown dressed exactly as he advised courtiers to dress, in elegant, but subdued, clothing that would enhance the splendor of the court, but never outshine the ruler. Scala/Art Resource, NY Bennozzo Gozzoli: Procession of the Magi, 1461 This segment of a huge fresco covering three walls of a chapel in the Medici Palace in Florence shows members of the Medici family and other contemporary individuals in a procession accompanying the biblical three wise men (magi in Italian) as they brought gifts to the infant Jesus. The painting was ordered by Cosimo and Piero de’ Medici, who had just finished building the family palace in the center of the city. Reflecting the self-confidence of his patrons, Gozzoli places the elderly Cosimo and Piero at the head of the procession, accompanied by their grooms. The group behind them includes Pope PiusII (in the last row in a red hat that ties under the chin) and the artist (in the second to the last row in a red hat with gold lettering). Scala/Art Resource, NY The Print Shop This sixteenth-century engraving captures the busy world of a print shop: On the left, men set pieces of type, and an individual wearing glasses checks a copy. At the rear, another applies ink to the type, while a man carries in fresh paper on his head. At the right, the master printer operates the press, while a boy removes the printed pages and sets them to dry. The well dressed figure in the right foreground may be the patron checking to see whether his job is done. Giraudon/ArtResource, NY The Growth of Printing in Europe The speed with which artisans spread printing technology across Europe provides strong evidence for the existing market in reading material. Presses in the Ottoman Empire were first established by Jewish immigrants who printed works in Hebrew, Greek, and Spanish. Use this map and those in other chapters to answer the following questions: •1 What part of Europe had the greatest number of printing presses by 1550? Why might this be?•2 Printing wasdeveloped in response to a market for reading materials. Use Maps 11.2 and 11.3 (pages 340 and 346) to help explain why printing spread the way it did.•3 Many historians also see printing as an important factor in the spread of the Protestant Reformation. Use Map 14.2 (page 468) to test this assertion. Gentile and Giovanni Bellini: Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria (1504–1507) The Venetian artists Gentile and Giovanni Bellini combine figures and architecture in this painting of Saint Mark, the patron saint of Venice. Saint Mark (on the platform) is wearing ancient Roman dress. Behind him are male citizens of Venice in sixteenth-century Italian garb. In front of him are Ottoman Muslim men in turbans, Muslim women in veils, and various other figures. The buildings in the background are not those of first-century Alexandria (where Saint Mark is reported to have preached) but of Venice and Constantinople in the sixteenth century. The setting is made even more fanciful with a camel and a giraffe in the background. The painting glorifies cosmopolitan Venice’s patron saint, amore important feature for the Venetian patron who ordered it than was historical accuracy. Its clear colors and effective perspective and the individuality of the many faces make this a fine example of Renaissance art. Scala/Art Resource, NY Leonardo da Vinci, Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine. The enigmatic smile and smoky quality of this portrait can be found in many of Leonardo's works. Czartoryski Museum, Krakow/TheBridgeman Art Library Artemisia Gentileschi: Esther Before Ahaseurus (ca 1630) In this oil painting, Gentileschi shows an Old Testament scene of the Jewish woman Esther who saved her people from being killed by her husband, King Ahaseurus. This deliverance is celebrated in the Jewish holiday of Purim. Both figures a rein the elaborate dress worn in Renaissance courts. Typical of a female painter, Artemisia Gentileschi was trained by her father. She mastered the dramatic style favored in the early seventeenth century and became known especially for her portraits of strong biblical and mythological heroines. Image copyright ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY Carpaccio: Black Laborer son the Venetian Docks (detail) Enslaved and free blacks, besides working as gondoliers on the Venetian canals, served on the docks: here, seven black men careen—clean, caulk, and repair—a ship. Carpaccio's reputation as one of Venice's outstanding painters rests on his eye for details of everyday life. Gallerie dell’Accademia,Venice/Scala/Art Resource, NY Italian City Scene In this detail from a fresco of the life of Saint Barbara by the Italian painter Lorenzo Lotto, the artist captures the mixing of social groups in a Renaissance Italian city. The crowd of men in the right foreground surrounding the biblical figures includes wealthy merchants in elaborate hats and colorful coats. Two mercenary soldiers carrying a sword and a pike), probably in hire to acondottiero, wear short doublets and tight hose stylishly slit to reveal colored undergarments, while boys play with toy weapons at their feet. Clothing like that of the soldiers, which emphasized the masculine form, was frequently the target of sumptuary laws for both its expense and its “indecency.” At the left, women sell vegetables and bread, which would have been a common sight at any city marketplace. At the very rear, men judge the female saint, who was thought to have been martyred for her faith in the third century. Scala/Art Resource, NY Renaissance Wedding Chest (Tuscany, late fifteenth century) Well-to-do brides provided huge dowries to their husbands in Renaissance Italy, and grooms often gave smaller gifts in return, such as this wedding chest. Appreciated more for their decorative valuethan for practical storage purposes, such chests were prominently displayed in people's homes. This 37-inch by 47-inch by 28-inch chest is carved with ascene from classical mythology in which Ceres, the goddess of agriculture, is searching for her daughter Proserpina also known as Persephone), who has been abducted by Pluto, the god of the underworld. The subject may have been a commentary on Renaissance marriage, in which young women often married much older men and went to live in their houses. Philadelphia Museumof Art. Purchased with the BloomfieldMoore Fund and with Museum Funds, 1944[1944-15-7] MAP 13.3 Spain in 1492 The marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469 represented a dynastic union of two houses, not a political union of two peoples. Some principalities, such as León (part of Castile) and Catalonia (part of Aragon), had their own cultures, languages, and legal systems. Barcelona, the port city of Catalonia, controlled a commercial empire throughout the Mediterranean. Most of the people in Granada were Muslims, and Muslims and Jews lived in other areas as well. Felipe Bigarny: Ferdinand and Isabella In these wooden sculptures, the Burgundian artist Felipe Bigarnyportrays Ferdinand and Isabella as paragons of Christian piety, kneeling at prayer. Ferdinand is shown in armor, a symbol of his military accomplishments and masculinity. Isabella wears a simple white head-covering rather than something more elaborate to indicate her modesty, a key virtue for women, though her actions and writings indicate that she was more determined and forceful than Ferdinand. Capilla Real, Granada/LauriePlatt Winfrey, Inc.