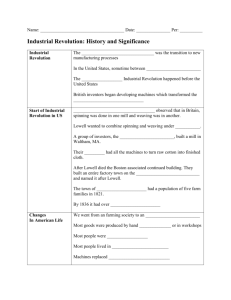

American Textiles History English inventors in the 18th century

advertisement

American Textiles History English inventors in the 18th century began to automate textile cottage industry processes including carding, spinning and weaving. James Hargreaves developed the Spinning Jenny, a device which replaced eight hand spinners in one operation. Richard Arkwright assembled these processes and started the first factory on the Derwent River in Cromford, England in 1771. Spinning Jenny Image: Engels Museum Wuppertal, Germany Source: Wikipedia "spinning jenny" Following the American Revolution, several founding fathers felt manufacturing should remain in England. Alexander Hamilton felt otherwise and wanted to establish a model mill village in Paterson, New Jersey. His ideas were ahead of their time. The "National Manufactory" went out of business in 1796. Samuel Slater of Rhode Island visited several mills owned by Arkwright and associates, memorized the essential features and returned to the US. In 1792, he opened a yarn spinning mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, the first successful automated yarn spinning in the US. In 1814, James Cabot Lowell of Boston built a factory in Waltham, up the Charles River from Boston. Later, the Boston Associates built an entire mill town on the Merrimack River, and later named it "Lowell" in memory of James Cabot Lowell. Boston Manufacturing Co. Logo in 1918 Image: Textile Brands and Trademarks Early Industry Locations Image: National Park Service 1793 - Eli Whitney and Hogden Holmes developed a simplified method of removing the cotton lint from the seed. Whitney’s, and especially Holmes' saw tooth gin, revolutionized the cotton industry by dramatically increasing the productivity of cotton ginning Gins Left: Eli Whitney's Cotton Gin Image: US Patent Office Right: Drawing of Holmes' gin Image: www.Pratthistory.com In the early 1800s, cotton was raised in the southern United States and exported to mills in England and the north. Leaders such as William Gregg of South Carolina advocated a home-based textile industry for the south but the time was not right. Northern mills resisted to growth of mills outside New England. Textile machinery was built in New England and New Jersey and imported from Europe. William Gregg Early Advocate of a Southern Textile Industry. Image: Hampstead, NC Chamber of Commerc After the Civil War, the south slowly replaced slaves with free workers. The industry remained largely in the north until after the 1880s. Leaders such as Edwin Michael Holt and family of Alamance County, North Carolina built mills in large numbers throughout the south as the 19th century closed. Glencoe Cotton Mill and mill village are preserved today. www.textileheritagemuseum.org Cotton mills in New England began to decline in importance. Merchants contracted for goods through agents. The Cone family moved from Baltimore to Greensboro and brokered sales. The Belk family bought goods from Cone to sell in the dry goods stores. Merchants such as Marshall Fields of Chicago bought goods from mills through intermediaries. Later, in order to better control supply, the Cones and the Fields built mills of their own, e.g., Cone Mills and Fieldcrest Mills. Machinery was imported from the north and from Europe. World War I and the naval blockage imposed by England on German shipping, and the use of U-boats by Germany to harass English vessels brought the realization that the United States must be independent of England and Germany for machinery and dyestuffs. New companies emerged to satisfy the war effort and remained strong for several decades following the war. World War II once again emphasized the need for self-sufficiency. Following the war, however, imported machinery and dyes, especially from Germany and Switzerland, once again supplemented and eventually replaced domestic supply. American textile companies thrived with the use of imported machinery and dyestuffs. In the 1990s, a new world order began to replace the Made in the USA ideas. Buying from the lowest cost producer drove many textile manufacturers out of the production side and into imports. Manufacturing companies changed to marketing companies. Source: Dunwell, Steve, The Run of the Mill. Boston: David R. Godine – Publisher, 1978. An excellent discussion with many illustrations of early technology and mill development. Note: This is my hobby. If you have an interest in the history of the industry, please return again as the site is developed. If you wish to contribute information or suggest research areas, Contact: mock.gary@yahoo.com Copyright 2007-2010 Gary N. Mock http://www.textilehistory.org/