ppt

advertisement

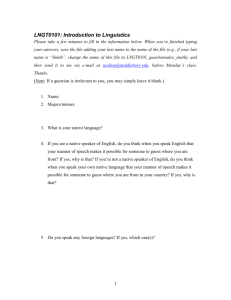

Languages in Contact Maarten Mous Leiden University Structure of talk • • • • why talk about language contact here historical linguistics models for language contact linking results of language contact to prior socio-linguistic situations • prehistoric contact Linguistics-Genetics The link between linguistics and genetics is the speaker. Speakers speak different languages, shift to another language, become member of a different speech community. This is one obvious reason why the issue of language contact is important for this conference. The linguistic genetic tree is an abstraction that has filtered out the admixture part of the linguistic history. 15 what to correlate to • speech community (multilingualism: everybody belongs to several) • ≠ • ethnic unit: relevance varies, not constant, multiple (clan affiliations) Community • • • • • speaker’s community ethnic community tribe-clan; caste economic community geography of settlement what do we compare? Historical linguistics • = study of language change • basis is reconstruction of language change through the comparative method • added result is a genetic tree of related languages; not central aim and an abstraction • contact linguistics deals with the influence of other languages on change Historical linguistics2 • Contact linguistics presumes the comparative method and does not aim at questioning it • contact linguistics adds to a fuller understanding of the linguistics history; comparative method shows only part of the story and may give wrong impression of neat split15 • scientific robustness of regular sound change in comparative method is absent in contact linguistics comparative method • strong in sound laws • lexicon reconstruction; issue of conservative basic vocabulary (sometimes precisely unstable; what is basic?) • morphology (word structure): most resistant to language induced change; levelling; grammaticalization (lexical sign>grammar sign; can it predict? • syntax: difficult, often linked to typology, fossilised in morphology Dating by glottochronology • retention rate as measure for time depth based on percentage of cognate forms in standard list of basic vocabulary of related languages • heavily criticised for premise that change is constant over time. E.g. Blust showed important variation in change within branches of Austronesian.6 • retention rate different across vocabulary • look-a-like rather than cognate form Starostin’s modification25 • exclude borrowings (=“chance mutations”) • variable factor over time (words become more stable with age) • etymological roots from texts in stead of basic word list • newly calibrated value for factor • only works when one knows linguistic history • evaluation: still problematic for revolutions of language change (quite common) Factors affecting rate of change • literacy (more borrowings) • existence of a standard • size of language community (more tolerance to variation; quicker spread of change) • attitude of speakers (blocks recognizable borrowings) • • • • language mixture processes of transfer sociolinguistic situation demographic situation restrictions on borrowability • Moravcsik (1978) • Heath (1978) • Matras (2000) Proposed restrictions Campbell (1993) • structural-compatibility requirement (counter-examples) • fit with innovation possibilities of the borrowing language (counter-examples) • grammatical gaps tend to be filled by borrowings (but not all) • morphological borrowing as replacement (but not all) • free standing grammatical forms are more easily borrowed than bound morphemes (but cases of borrowed bound morpheme replacing free standing) • borrowability according to ranking of categories • principle of functional load: if embedded in system then not easily borrowed • etc Everything can be borrowed • Both Campbell7 and Thomason27 hold the view that all proposed constraints in borrowing are nothing but tendencies. There are always exceptions • Interpretation of counter-examples sometimes open for dispute. Mixed language Ma’a as example of borrowing of Bantu grammar29 is no longer valid counterexample if one accepts that language shift took place. • distinction between concept and content is needed. emergence of a noun class system through contact has been proposed but no Bantu noun class system (with the typical markers) has ever happened. Thomason • anything is possible • implicational/chronological scales • ordinary processes extra-ordinary results Basic vocabulary • in certain circumstances prone to change: language/register creation for identity or fear/respect • stable vocabulary: Leipzig project to establish it empirically; lists on basis of retained items in various families (Lohr 1999) • can be different across language family Shift • complete shift (very common) • shift with effect of original language on recognizable community; with effect on language as a whole • shift with carry over of vocabulary (e.g. pygmy technical vocabulary) • arrested shift, u-turn when too late, reborrowing of original vocabulary Van Coetsem frame van Coetsem 1988,2000, Winford 2003 • Differences in stability across language components (grammar more stable than lexicon) • Recipient language agentivity (borrowing) • Source language agentivity (imposition) • Linguistic dominance (not social) in bilingualism contact situations 1. Recipient L agentivity AB 2. Source L agentivity AB Agents / Agentivity imitation / adaptation 1: borrowing 2: imposition processes in individual Examples • RecL activity, borrowing, extreme case Media Lengua Quechua with every lexeme borrowed from Spanish • SourceL activity: structures of dominant language in recipient language. Dominant language can be the new language influencing the language which is in process of being abandoned in cognitive and grammatical structure. Asia Minor Greek (RL): Turkish (SL) dominant. (and RL activity when speaking T) • transfer of structure under RL activity differs from transfer of structure under SL activity • RL: close to lexicon: function words, derivation • SL: conceptualization, categories, structure • result of adaptation in RL activity can be similar to that in SL activity, e.g. pronunciation of English borrowings in Hindi and Hindi pronunciation of English second language acquisition • • • • most studies on formal learning few on informal learning at ages 9, 16 few on learning strategies are there restrictions on vocabulary if >3 languages are acquired? Individual – Community • Model refers to the mind of the individual • Essential is language as social construct: establishment of the norm (variation is larger when various SLs) reconstructing past contact situations • Assumption: contact situations in the past are not different from those now • If all things equal the simplest wins • Propose scenario to explain present outcome problems with the scenario game • limits of imagination • never are all other things equal Proposed correlations socio-history language change • Guy11-Ross23 based on Van Coetsem dominant language of bilinguals Agents of change Social motivation to adopt change to resist change Structural domains borrowing imposition recipient language source language I native speakers prestige II nonnative emblema -ticity emblema... ticity words, words morphemes I non-native II native communicat communicativ ive need e simplicity ... emblematicity phonology syntax borrowing dominant language of recipient language bilinguals I native II non-native Social motivation to adopt change prestige emblematicity to resist change emblematicity ... Structural domains unstable first words, morphemes words Agents of change dominant language of bilinguals imposition source language I II Agents of change non-native native Social motivation to adopt change communicative communicative need simplicity ... emblematicity to resist change Structural domains stable first phonology syntax Additions by Reh21 If only migration as cause for contact Added factors • Intensity of contact • Linguistic heterogeneity of community Other factors • • • • • identifiable group after “migration” degree of bilingualism language attitude size of group prestige Comparable situations • • • • • Northern Songhay Mozambican Swahili Pygmies Creole studies etc languages of pygmies10 • speak different languages • which probably were once language of their patron • also speak language of patron • pygmy special vocabulary • patrons and their language are link and obstacle to outside world (forest pygmies have better knowledge of languages of wider communication) Creole languages • study link socio-history and outcome of language change • similar sociolinguistic situations for a number of them • similar outcome • separate field of study Mixed Languages5 • grammar and (basic) lexicon not from the same source • originate in new communities of systematic mixed marriage: mother’s grammar with father’s lexicon • originate as extended argot of itinerant and other groups who maintain identity under pressure: grammar of dominant language, deviant lexicon • note the genetic difference for the two scenario’s Contact situations • • • • • multilingualism in the city, re-settlements, migration, seasonal work, etc., etc. gene flow (and language contact) • • • • • • expulsion (ostracism as punishment) occasional sex (e.g. ritual: outside group) ritual expert (high status, founder of group) marriage pattern (e.g. women from outside) war (women from outside) refugees (e.g. masters in problems in client hunter group, pygmies, Aasax) contact situations in prehistoric times • symbiosis of hunters - farmers / cattle people • agriculture / cattle stratification in limited area (East Turkana) • reconstitution of bands of hunters • war • marriage outside group • expulsion hunter-cattle • • • • • Dorobo division of labour across gender speech patterns in settlement ethnic diversity imbalance in power hunting and speech • gender division • ways of hunting: individual / cooperating groups • short / long hunting expeditions • traps and ownership • special communication during hunt Dixon’s Rise & Fall9 • punctuation versus equilibrium • In situations/periods of punctuation languages diverge quickly enough for the tree model to be valid • In situations of equilibrium, contact is main force for change • Situations of equilibrium are characterised by equality (in size, prestige) • Periods of punctuation have external causes (e.g. development of agriculture) Dixon2 • External causes can be linked to archaeology, history of climate, etc. • provides model for Australia • addresses pre-reconstruction period Dixon3 • can linguistic history still be traced • punctuation and equilibrium kind of linguistic events are simultaneous in same area. For example the Bantu languages are similar due to recent spread and common ancestor, yet the equality properties and the linguistic diffusion are valid for Bantu • Africa must have had many situations of punctuation over the last millennia but also diffusion Time gap • beginning of human language • estimate of oldest families 10,000 years • divergence in (linguistic) genetic variation in Africa (>100,000) and in the recently inhabited areas of Papua (50,000) and Americas (20,000) • consequences of time gap: no linguistic knowledge about the period; most language families in Africa must have disappeared; can we extrapolate knowledge about human language to earlier periods? References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Aikhenvald, Alexandra and R.M.W. Dixon (eds) 2001. Areal Diffusion and Genetic Inheritance. Problems in Comparative Linguistics. Cambridge: CUP. Aikhenvald, Alexandra and R.M.W. Dixon 2001. Introduction. In Aikhenvald, Alexandra and R.M.W. Dixon (eds), 1-26. Andersen, Henning 1988. Center and periphery: adoption, diffusion, and spread. In Historical Dialectology Regional and Social, ed. by Jacek Fisiak. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp.39-83. Bakker, Peter and Maarten Mous (eds.) 1994. Mixed languages: 15 case studies in language intertwining. (Studies in Language and Language Use, 13.) Amsterdam: IFOTT. Bakker, Peter. 1997. "A language of our own": The genesis of Michif, the mixed Cree-French language of the Canadian Métis. (Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, 10.) New York: Oxford University Press. Blust, Robert 2000. Why lexicostatistics doesn’t work: the ‘universal constant’ hypothesis and the Austronesian languages. In Time Depth in historical Linguistics ed. by Renfrew e.a. Vol 2, pp.311-331. Campbell, Lyle 1993. On proposed universals of grammatical borrowing. In Historical linguistics 1989: Papers from the 9th international conference on historical linguistics, Rutgers university, 14-18 August 1989, ed. by Henk Aertsen and Robert J. Jeffers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 91-109. Coetsem, Frans van 2000. A general and unified theory of the transmission process in language contact. Heidelberg: C. Winter Verlag. Dixon, R.M.W. 1997. The rise and fall of languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Duke, Daniel Joseph 2001. Aka as a contact language: sociolinguistic and grammatical evidence. MA University of Texas at Arlington. Guy, Gregory R. 1990. The sociolinguistic types of language change. Diachronica 7: 47-67. Heath, Jeffrey 1978. Linguistic diffusion in Arnhem land. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. Lohr, Marisa 1999. Methods for the Genetic Classification of Languages. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge. Matras, Yaron 2000. How predictable is contact-induced change in grammar? In Time Depth in historical Linguistics, ed. by Renfrew e.a. Vol 2, pp. 563-584. McMahon, April Language, Time and Human Histories. Antwerp Papers in Linguistics 106: Language and Revolution/Language and Time: 156170. Muysken, Pieter 1997. Code-switching processes: Alternation, insertion, congruent lexicalization. In Martin Pütz (ed.) Language choices: Conditions, constraints, and consequences, pp.361-380. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. References 2 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. Myers-Scotton, Carol 1993a. Duelling languages: Grammatical structure in codeswitching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Myers-Scotton, Carol 1993b. Social motivations for codeswitching: Evidence from Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Myers-Scotton, Carol 2002. Contact linguistics; bilingual encounters and grammatical outcomes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Nurse, Derek 2000. Inheritance, contact, and change in two East African languages. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. Reh, Mechthild 1995. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Rekonstruirbarkeit von Soziohistorie aus Sprachdaten; am Beispiel der Kadugli-Krongo (Nuba-Berge, Sudan) Hamburg: Ms.. Renfrew, Colin, April McMahon and Larry Trask (eds) 2000. Time depth in historical linguistics. Cambridge: The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. Ross, Malcolm D. 1991. Refining Guy’s sociolinguistic types of language change. Diachronica 8:119-129. Ross, Malcolm D. 1996. Contact-induced change and the comparative method: Cases from Papua New Guinea. In Mark Durie and Malcolm Ross (eds.) The comparative method reviewed: Regularity and irregularity in language change, pp. 180-217. New York: Oxford University Press. Starostin, Sergei Comparative-historical linguistics and lexicostatistics In Time Depth in historical Linguistics, ed. by Renfrew e.a. Vol 1., pp.223259. Thomason, Sarah G. 1995. Language mixture: Ordinary processes, extraordinary results. In Carmen Silva-Corvalán (ed.) Spanish in four continents: Studies in language contact and bilingualism, pp. 15-23. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. Thomason, Sarah G. 2001. Language Contact: An introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Thomason, Sarah G. and Terrence Kaufman 1988. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press. Thomason, Sarah Grey 1998. On reconstructing past contact situations. In The life of language; papers in linguistics in honor of William Bright, ed. by Jane H. Hill, P.J. Mistry and Lylel Campbell. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 153-168. Winford, Donald 1997. Creole formation in the context of contact linguistics. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 12:131-151. Winford, Donald 2003. Contact-induced changes - Classification and Processes. OSUWPL 57, Summer 2003, 129-50. Winter, Jürgen-Christoph 1979. Language shift among the Aasáx, a hunter-gatherer tribe in Tanzania: A historical and sociolinguistic case-study. Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika (SUGIA) 1:175-204. Orr, Robert A. 1999. Evolutionary Biology and Historical Linguistics (Review of Dixon 1997). Diachronica 16: 123-157.