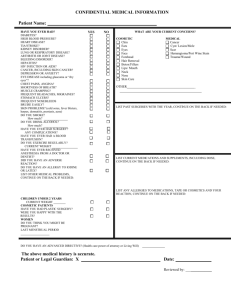

MBS Reviews - Vulvoplasty Report - Word 1526 KB

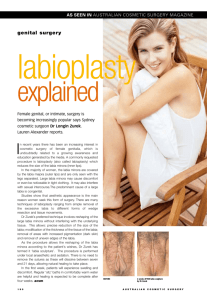

advertisement