Psychosis and ACT - Association for Contextual Behavioral Science

advertisement

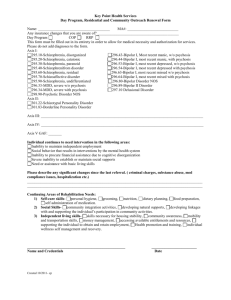

Acceptance & Commitment Therapy for people with persisting psychosis: Rationale, evidence, and work in progress from Melbourne, Australia John Farhall, Neil Thomas, Fran Shawyer School of Psychological Science, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia Steven Hayes University of Nevada, USA ACBS World Conference June 2010 Reno, Nevada 1 Overview • ACT for psychosis efficacy research so far • Our current trial – Design – Adaptations of ACT for psychosis – Preliminary results Arguments for applying ACT to psychosis Several features and components of ACT suggest its value in working with persisting hallucinations or delusions • Acceptance Persisting symptoms are difficult to change – learning ways to get on with life even though they persist is a realistic focus for a therapy • Mindfulness & defusion are promising alternatives to unsuccessful coping with symptoms by resistance, suppression, avoidance or engulfment • The values focus - getting in touch with what is important in your life and translating this into everyday living - is consistent with recovery models ACT and psychosis treatment studies Two case studies in English Bach and Hayes, 2002 (Pankey & Hayes, 2003; Veiga-Martinez et al., 2008) 80 inpatients with positive symptoms randomized to either ACT or usual treatment Brief intervention: 3 hours of ACT (4 sessions); all but one session inpatient Significant reduction in believability of delusions and in hospital readmission rates in the following 4 months Gaudiano & Herbert (2006) Similar study showing improvements in overall symptoms (BPRS) and reduction in distress associated with hallucinations Importance of these clinical trials • Demonstration that ACT can be conducted for people presenting with acute psychosis • Evidence that a brief ACT intervention may impact on the illness presentation (re-hospitalisation; some aspects of symptom severity) • Evidence that believability of psychotic symptoms mediates change – supportive of the theoretical base Limitations of these two trials • No standardised control treatment in either study • Assessments not blind (tho hospitalisation outcomes notable) • Participants had a range of diagnoses • Restricted to in-patients in USA • Variations in ‘dose’ received (1-5 sessions) • Gaudiano & Herbert study was underpowered – may explain failure to replicate Bach & Hayes’ main results on hospitalisation and believability • Gaudiano & Herbert’s objective measure of positive symptoms (BPRS) did not improve, but subjective distress did… Is the evidence base sufficient for ACT to be a recommended psychosis treatment? No! (not yet) • ACT (in general) does not yet meet the criteria for an ‘empirically supported treatment’ (Ost, 2008), due to insufficient quality in research studies • ACT for psychosis has not yet been subjected to a randomised controlled trial that meets Consort criteria for rigor And • (… there is an alternative with more substantive evidence - CBT for psychosis) So, what have we been doing? 8 Unpublished trial of a CBT + ACT intervention (Shawyer et al, in preparation). • Our previous work in CBT for psychosis gradually moved away from a therapeutic focus on the content of voices to coping with the experience (i.e. the phenomenon) • The Treatment Of Resistant Command Hallucinations (TORCH) trial – 3 groups: A combined Belief Modification (CBT) & ACT intervention; Befriending; and waitlist (n=42) – Little difference between groups, but underpowered – However, observation of good response to ACT elements Development of an ACT relevant process measure for hallucinations • Voices Acceptance & Action Scale (VAAS – Shawyer et al, 2007) items address general and command hallucinations Acceptance items Action items – I struggle with my voicesR My voices stop me doing the things I want to doR • Short version (VAAS-9) suitable for any hallucinated voices now piloted (Kirk Ratcliff’s thesis) • Two factors (Acceptance & Autonomy). Only weakly related to voice severity • Strongly related to convergent measures of validity (AAQ II; SMVQ) • Negatively related to measures of depression (BDI), voice distress (PSYRATS) and disability (Sheehan Disability Scale) A Randomised Controlled Trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Medication-Resistant Psychosis Design features • A single blind RCT of ACT for persisting positive symptoms • A credible comparison treatment (Befriending) • Targets community-residing consumers with medication-resistant symptoms (a more relevant target group for Australia) • Investigating therapy process factors – Non-specific & specific factors in each therapy • Uses validated measures • Independent blind rating of audiotapes for treatment fidelity – developed the ACT for Psychosis Adherence and Competence Scale APACS (Susan Pollard’s thesis) The therapies • 8 x 50 min sessions course of therapy • 4 therapists all deliver both therapies • Local peer supervision plus specialist supervision from Steven Hayes • Manualised ACT for psychosis – Six modules relating to the six components of ACT – Elements from modules conducted flexibly in parallel across the therapy • Manualised Befriending intervention (Bendall et al) 14 Comparison Therapy - Befriending • Used as a control condition for ‘non-specific’ factors in therapy e.g. contact time with a therapist and emotional and social support • Conversation-based or low-key activity-based (play a game; have a coffee; go for a walk) • Focus is on good things that are happening and topics of interest to participants; symptoms and problems are explicitly not talked about • Originally developed as a treatment for depression • Not a “no-treatment” condition – some efficacy in depression; some evidence it can reduce symptoms of psychosis in the short-term (Sensky et al., 2000) • Assumed to have different mechanisms of action Reasons for modifying ACT materials and strategies when working with psychosis 1. Engagement variability 2. Reduced information processing capacity 3. Higher order cognitive deficits 4. Perception of internal events as external 5. Compelling salience and strong emotional investment in symptoms 6. Delusions or voices may be positive/valued Engagement in therapy • Challenges: – Often referred by others vs self-motivation driving therapy – Absence of distress around ego-syntonic delusions & voices may reduce motivation for change • Strategies: – Start with values work Stimulus overload • Challenges: – Stimulus overload or too much emotional arousal can lead to symptom exacerbation • Strategies: – Caution required with exposure/exercises applied directly to symptoms e.g., Taking your mind for walk – Keep to a matter of fact, collaborative, psychoeducational tone; high levels of emotion unlikely to be helpful; Cognitive deficits • Challenges: – Problems in verbal learning; concentration; abstract thinking may interfere with understanding metaphors, retaining information • Strategies: – Use more concrete and briefer written material – Slow the pace (in the session and over time) but be as active as possible – Use simple, short metaphors – Adapt standard metaphors & exercises to personalise as much as possible – Physical props if possible (e.g., fingertraps, chessboard, towel) – Record sessions and burn CDs to take home – Use Therapy folder to store copies of metaphors, CDs of sessions – Repetition (using same or variants of exercises/metaphors) – Christmas tree – hang new ideas off one that has made a significant impact Perception of internal events as external • Challenges: – Mindful acceptance and defusion are intended to be directed at internal experiences BUT psychotic symptoms are subjectively experienced as external & more likely to be viewed as fact than thought - undermines the rationale • Strategies: – General approach: Take on client’s terminology for psychosis/symptoms (not well, concerns) – Step around issues of reality (entangling). Refer back to having space to move, workability, to live - letting values be the “real” thing that is important – Work with internal responses to psychotic experiences – The client may tolerate defusion and mindfulness anyway (in the absence of the usual rationale of them being internal events) Compelling salience and strong emotional investment in symptoms • Challenges: – A high investment in delusions over the long term means that direct work may not be feasible • Strategies: – a focus on values & commitment & small steps may open up areas of living that have been neglected – continue generic work – learning ACT skills, e.g., defusion using nondelusional material, openness to discomfort Delusions or voices may be positive/valued • Challenges: – Absence of struggle with internal experiences - Positive/valued delusions or voices may be a form in which experience is being avoided - rather than aversive • Strategies: – If no struggle present start with values and goals. – If delusions are expressed in identified goals, drill down to underlying value – If delusions expressed in values (e.g. living a spiritual life), focus on non-delusional values [since already doing a lot in the (delusional) value area!] Participants • Target: 100 participants • Outpatients from public mental health services and nongovernment psychiatric rehabilitation providers across Melbourne • Inclusion criteria – Age 18-65 – Diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (SCID) – Ongoing distressing delusions or hallucinations (PsyRATS) – Taking antipsychotic medication for > 1 year – Absence of intellectual disability or neurological disorder 23 Primary Measures • Outcome measures administered pre-therapy, post-therapy and 6month follow-up (independent blind raters) • Symptom-related outcomes – Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS) – Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) • Behaviour-related outcomes – Time Budget Measure (Jolley et al) – Social Functioning Scale (SFS) • Process measures – Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ II) – Voices Acceptance and Action Scale (Shawyer et al) 24 Assessed for eligibility: n = 69 Randomised: n = 48 Excluded: n = 21 17 ineligible 1 declined participation 2 withdrew during assessment Allocated to ACT: n = 24 Allocated to Befriending: n = 24 Completed therapy: n = 19 Currently in therapy: n = 5 Completed therapy: n = 17 Currently in therapy: n = 5 Withdrew during therapy: n = 2 Post therapy: n = 19 Post-therapy: n = 17 Completed assessment: n = 19 Completed assessment: n = 16 Withdrew during assessment: n = 1 Follow-up: n = 19 Follow-up: n = 16 Completed assessment: n = 8 Pending 6-mo assessment: n = 11 Completed assessment: n = 7 Pending 6-mo assessment: n = 9 25 Results: Psyrats post-therapy change 26 Results: participant ratings of change Since receiving therapy, my problems with psychosis are... ACT Befriending ‘no different’ ‘better’ or ‘much better’ 2 15 (12%) (88%) 8 5 (62%) (38%) p = .007 27 Lifengage Team Chief Investigators Therapists Research assistants Dr John Farhall Dr Fran Shawyer Kate Ferris Dr Fran Shawyer Dr Neil Thomas Paula Rodger Dr Neil Thomas Dr John Farhall Emma White Prof David Castle Carole Pitt Prof David Copolov Prof Steven Hayes www.lifengage.org.au j.farhall@latrobe.edu.au Postgraduate students Specialist supervision Tory Bacon Prof Steven Hayes Suzanne Pollard Megan Trickey 28