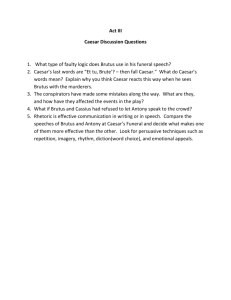

File - 12 Ancient History

advertisement

Personal relationships: Julia; Cleopatra VII; Brutus, Mark Antony; Cicero Julia Julia was the only daughter of Julius Caesar. Her mother was Cornelia, Caesar’s first wife. "… as in former days the Divine Julius after the loss of his only daughter…" (Tacitus, Annals, III 6) Julia was born about 76 BC. As part of the political relationship of the First Triumvirate, Caesar had her married to Pompey in April 59 BC. "Furthermore, a tie of marriage was cemented between Caesar and Pompey, in that Pompey now wedded Julia, Caesar's daughter." (Velleius Paterculus, ii. 44) Plutarch records Pompey’s affection for his new wife: "Lucullus pleaded old age, and retired to take his ease, as superannuated for affairs of State; which gave occasion to the saying of Pompey, that the fatigues of luxury were not more seasonable for an old man than those of government. Which in truth proved a reflection upon himself; for he not long after let his fondness for his young wife seduce him also into effeminate habits. He gave all his time to her, and passed his days in her company in country-houses and gardens, paying no heed to what was going on in the forum. Insomuch that Clodius, who was then tribune of the people, began to despise him, and engage in the most audacious attempts." (Plutarch Life of Pompey, 48) Julia was equally in love with her husband (in the following extract, the election of aediles is in 55 BC. Julia falls pregnant again and dies in 54 BC): "These entertainments brought him great honour and popularity; but on the other side he created no less envy to himself, in that he committed the government of his provinces and legions into the hands of friends as his lieutenants, whilst he himself was going about and spending his time with his wife in all the places of amusement in Italy; whether it were he was so fond of her himself, or she so fond of him, and he unable to distress her by going away, for this also is stated. And the love displayed by this young wife for her elderly husband was a matter of general note, to be attributed, it would seem, to his constancy in married life, and to his dignity of manner, which in familiar intercourse was tempered with grace and gentleness, and was particularly attractive to women, as even Flora, the courtesan, may be thought good enough evidence to prove. It once happened in a public assembly, as they were at an election of the aediles, that the people came to blows, and several about Pompey were slain, so that he, finding himself all bloody, ordered a change of apparel; but the servants who brought home his clothes, making a great bustle and hurry about the house, it chanced that the young lady, who was then with child, saw his gown all stained with blood; upon which she dropped immediately into a swoon, and was hardly brought to life again; however, what with her fright and suffering, she fell into labour and miscarried; even those who chiefly censured Pompey for his friendship to Caesar, could not reprove him for his affection to so attached a wife. Afterwards she was great again, and brought to bed of a daughter, but died in childbed; neither did the infant outlive her mother many days. Pompey had prepared all things for the interment of her corpse at his house near Alba, but the people seized upon it by force, and performed the solemnities in the field of Mars, rather in compassion for the young lady, than in favour either for Pompey or Caesar; and yet of these two, the people seemed at that time to pay Caesar a greater share of honour in his absence, than to Pompey, though he was present." (Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 53) "About the fourth year of Caesar's stay in Gaul occurred the death of Julia, the wife of Pompey, the one tie which bound together Pompey and Caesar in a coalition which, because of each one's jealousy of the other's power, held together with difficulty even during her lifetime; and, as though fortune were bent upon breaking all the bonds between the two men destined for so great a conflict, Pompey's little son by Julia also died a short time afterwards." (Velleius Paterculus, ii. 44) "At this same time the wife of Pompey died, after giving birth to a baby girl. And whether by the arrangement of his friends and Caesar's or because there were some who wished in any case to do them a favour, they caught up the body, as soon as she had received proper eulogies in the Forum, and buried it in the Campus Martius. It was in vain that Domitius opposed them and declared among other things that it was sacrilegious for her to be buried in the sacred spot without a special decree." (Dio Cassius, 39.64) Caesar commemorated his daughter in 46 BC: "Caesar, upon his return to Rome, did not omit to pronounce before the people a magnificent account of his victory, telling them that he had subdued a country which would supply the public every year with two hundred thousand attic bushels of corn, and three million pounds weight of oil. He then led three triumphs for Egypt, Pontus, and Africa, the last for the victory over, not Scipio, but king Juba, as it was professed, whose little son was then carried in the triumph, the happiest captive that ever was, who of a barbarian Numidian, came by this means to obtain a place among the most learned historians of Greece. After the triumphs, he distributed rewards to his soldiers, and treated the people with feasting and shows. He entertained the whole people together at one feast, where twenty-two thousand dining couches were laid out; and he made a display of gladiators, and of battles by sea, in honour, as he said, of his daughter Julia, though she had been long since dead. When these shows were over, an account was taken of the people, who from three hundred and twenty thousand, were now reduced to one hundred and fifty thousand. So great a waste had the civil war made in Rome alone, not to mention what the other parts of Italy and the provinces suffered." (Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 55) Julia’s tomb struck by lightning on Octavian’s entry into Rome, which was seen as a sign of great fortune for the future: "As he was entering the city on his return from Apollonia after Caesar's death, though the heaven was clear and cloudless, a circle like a rainbow suddenly formed around the sun's disc, and straightway the tomb of Caesar's daughter Julia was struck by lightning." (Suetonius, Life of Augustus, 95) Mark Antony In 54 BC Antony joined Caesar in Gaul, and, through Caesar’s influence, was elected Tribune of the Plebeians for 50 BC. As the civil war approached, Antony attempted to negotiate with the Senate on Caesar’s behalf. "Antony, being tribune, produced a letter sent from Caesar on this occasion, and read it, though the consuls did what they could to oppose it. But Scipio, Pompey's father-in-law, proposed in the senate, that if Caesar did not lay down his arms within such a time, he should be voted an enemy; and the consuls putting it to the question, whether Pompey should dismiss his soldiers, and again, whether Caesar should disband his, very few assented to the first, but almost all to the latter. But Antony proposing again, that both should lay down their commissions, all but a very few agreed to it. Scipio was upon this very violent, and Lentulus the consul cried aloud, that they had need of arms, and not of suffrages, against a robber; so that the senators for the present adjourned, and appeared in mourning as a mark of their grief for the dissension. Afterwards there came other letters from Caesar, which seemed yet more moderate, for he proposed to quit everything else, and only to retain Gaul within the Alps, Illyricum, and two legions, till he should stand a second time for consul. Cicero, the orator, who was lately returned from Cilicia, endeavored to reconcile differences, and softened Pompey, who was willing to comply in other things, but not to allow him the soldiers. At last Cicero used his persuasions with Caesar's friends to accept of the provinces, and six thousand soldiers only, and so to make up the quarrel. And Pompey was inclined to give way to this, but Lentulus, the consul, would not hearken to it, but drove Antony and Curio out of the senate-house with insults, by which he afforded Caesar the most plausible pretense that could be, and one which he could readily use to inflame the soldiers, by showing them two persons of such repute and authority, who were forced to escape in a hired carriage in the dress of slaves. For so they were glad to disguise themselves, when they fled out of Rome." (Plutarch, Life of Caesar, 30-31) During the civil war, he fought on Caesar’s side, taking command of the left wing of Caesar’s forces in battle. When Caesar was made Dictator, Antony was appointed his Master of the Horse. He administered Rome in Caesar’s absence, though they fell out over Antony’s poor administration in 47 BC. They were later reconciled and Antony was Caesar’s Consular partner in 44 BC. Whatever conflicts existed between the two men, Antony remained faithful to Caesar at all times. On February 15, 44 BC, during the Lupercalia festival, Antony publicly offered Caesar a diadem. This was an event pregnant with meaning: a diadem was a symbol of a king, and in refusing it, Caesar demonstrated that he did not intend to assume the throne. "And the fairest pretext for that conspiracy was furnished, without his meaning it, by Antony himself. The Romans were celebrating their festival, called the Lupercalia, when Caesar, in his triumphal habit, and seated above the Rostra in the market-place, was a spectator of the sports. The custom is, that many young noblemen and of the magistracy, anointed with oil and having straps of hide in their hands, run about and strike, in sport, at everyone they meet. Antony was running with the rest; but, omitting the old ceremony, twining a garland of bay round a diadem, he ran up to the Rostra, and, being lifted up by his companions, would have put it upon the head of Caesar, as if by that ceremony he were declared king. Caesar seemingly refused, and drew aside to avoid it, and was applauded by the people with great shouts. Again Antony pressed it, and again he declined its acceptance. And so the dispute between them went on for some time, Antony's solicitations receiving but little encouragement from the shouts of a few friends, and Caesar's refusal being accompanied with the general applause of the people; a curious thing enough, that they should submit with patience to the fact, and yet at the same time dread the name as the destruction of their liberty. Caesar, very much discomposed at what had past, got up from his seat, and, laying bare his neck, said, he was ready to receive the stroke, if any one of them desired to give it. The crown was at last put on one of his statues, but was taken down by some of the tribunes, who were followed home by the people with shouts of applause. Caesar, however, resented it, and deposed them." (Plutarch, Life of Mark Antony, 12) Marcus Tullius Cicero Cicero’s career was marked by his desire to save the Roman Republic, yet he was forced throughout his career to make many compromises. Much of his relationship with Caesar can be found in the Bradley handouts. The Catilinarian conspiracy brought them together in debate in the senate over the death sentence proposed for the conspirators: "When, therefore, it came to Caesar's turn to give his opinion, he stood up and proposed that the conspirators should not be put to death, but their estates confiscated, and their persons confined in such cities in Italy as Cicero should approve, there to be kept in custody till Catiline was conquered. To this sentence, as it was the most moderate, and he that delivered it a most powerful speaker, Cicero himself gave no small weight, for he stood up and, turning the scale on either side, spoke in favour partly of the former, partly of Caesar's sentence. And all Cicero's friends, judging Caesar's sentence most expedient for Cicero, because he would incur the less blame if the conspirators were not put to death, chose rather the latter; so that Silanus, also, changing his mind, retracted his opinion, and said he had not declared for capital, but only the utmost punishment, which to a Roman senator is imprisonment. The first man who spoke against Caesar's motion was Catulus Lutatius. Cato followed, and so vehemently urged in his speech the strong suspicion about Caesar himself, and so filled the senate with anger and resolution, that a decree was passed for the execution of the conspirators. But Caesar opposed the confiscation of their goods, not thinking it fair that those who had rejected the mildest part of his sentence should avail themselves of the severest. And when many insisted upon it, he appealed to the tribunes, but they would do nothing; till Cicero himself yielding, remitted that part of the sentence." (Plutarch, Life of Cicero, 21) "And yet there were some who were very ready both to speak ill of Cicero, and to do him hurt for these actions; and they had for their leaders some of the magistrates of the ensuing year, as Caesar, who was one of the praetors, and Metellus and Bestia, the tribunes. These, entering upon their office some few days before Cicero's consulate expired, would not permit him to make any address to the people, but, throwing the benches before the Rostra, hindered his speaking, telling him he might, if he pleased, make the oath of withdrawal from office, and then come down again. Cicero, accordingly, accepting the conditions, came forward to make his withdrawal; and silence being made, he recited his oath, not in the usual, but in a new and peculiar form, namely, that he had saved his country, and preserved the empire; the truth of which oath all the people confirmed with theirs. Caesar and the tribunes, all the more exasperated by this, endeavoured to create him further trouble, and for this purpose proposed a law for calling Pompey home with his army, to put an end to Cicero's usurpation. But it was a very great advantage for Cicero and the whole commonwealth that Cato was at that time one of the tribunes. For he, being of equal power with the rest, and of greater reputation, could oppose their designs. He easily defeated their other projects, and, in an oration to the people, so highly extolled Cicero's consulate, that the greatest honours were decreed him, and he was publicly declared the Father of his Country, which title he seems to have obtained, the first man who did so, when Cato gave it him in this address to the people." (Plutarch, Life of Cicero, 23) Rawson claims that Cicero was invited to join the coalition with Pompey and Crassus (First Triumvirate) as a fourth member, but that he refused as it would weaken the Republic. (Rawson, Cicero, p.106) In a letter to Varro on c. April 20, 46 BC, Cicero outlined his strategy under Caesar's dictatorship : "I advise you to do what I am advising myself – avoid being seen even if we cannot avoid being talked about. If our voices are no longer heard in the Senate and in the Forum, let us follow the example of the ancient sages and serve our country through our writings concentrating on questions of ethics and constitutional law". (Cicero, Ad Familiares 9.2) Cicero was not a part of the plot against Ceasar, though he wrote a letter in a letter in February 43, "How I could wish that you had invited me to that most glorious banquet on the Ides of March"! (Cicero, Ad Familiares 10.28) Cleopatra VII Cleopatra VII was born in January 69 BC. She was a co-ruler of Egypt with her father (Ptolemy XII Auletes) and later with her brothers/husbands Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV. During the civil war, after Caesar had defeated Pompey at the battle of Pharsalus, he followed Pompey to Egypt. On arrival, he was presented by Ptolemy XIII with Pompey’s severed head. Caesar was not impressed: although Pompey was his enemy and rival, he was a Roman of great achievement (and also the widower of his daughter, Julia). Caesar took control of Rome and sought a solution to the rival claims of Cleopatra and her brother to the throne. Cleopatra was keen to take advantage of Caesar’s anger with Pompey. She had herself rolled in a carpet, which was then given to Caesar. When it was unrolled, she appeared before him. Caesar had a ‘relationship’ with Cleopatra which resulted in a child, Caesarion (born 23 June, 47 BC – Caesar was about 30 years older than Cleopatra). Cleopatra came back to Rome with Caesar and probably stayed there for the next three years, until Caesar’s death. "As to the war in Egypt, some say it was at once dangerous and dishonourable, and noways necessary, but occasioned only by his passion for Cleopatra." (Plutarch, Life of Caesar, 48) "He had love affairs with queens too, including Eunoe the Mauretanian, wife of Bogudes, on whom, as well as on her husband, he bestowed many splendid presents, as Naso writes; but above all with Cleopatra, with whom he often feasted until daybreak, and he would have gone through Egypt with her in her state-barge almost to Aethiopia [i.e., Kush], had not his soldiers refused to follow him. Finally he called her to Rome and did not let her leave until he had ladened her with high honors and rich gifts, and he allowed her to give his name to the child which she bore. In fact, according to certain Greek writers, this child was very like Caesar in looks and carriage." (Suetonius, Julius Caesar, 52) Marcus Junius Brutus Brutus, as a young man, had opposed the First Triumvirate. Later, during the civil war, he fought against Caesar. After the defeat of the optimates at Pharsalus, He wrote to Caesar begging mercy and Caesar forgave him and allowed him further promotion – to praetor in 45 BC. For Brutus’ role in the plot to kill Caesar, see p.31 Ch 17. "From Larissa he wrote to Caesar, who expressed a great deal of joy to hear that he was safe, and, bidding him come, not only forgave him freely, but honoured and esteemed him among his chiefest friends." (Plutarch, Life of Brutus, 6) "But Brutus was roused up and pushed on to the undertaking by many persuasions of his familiar friends, and letters and invitations from unknown citizens. For under the statue of his ancestor Brutus, that overthrew the kingly government, they wrote the words, "O that we had a Brutus now!" and, "O that Brutus were alive!" And Brutus's own tribunal, on which he sat as praetor, was filled each morning with writings such as these: "You are asleep, Brutus," and, "You are not a true Brutus." Now the flatterers of Caesar were the occasion of all this, who, among other invidious honours which they strove to fasten upon Caesar, crowned his statues by night with diadems, wishing to incite the people to salute him king instead of dictator." (Plutarch, Life of Brutus, 9)