Assessment for Inquiry Science

advertisement

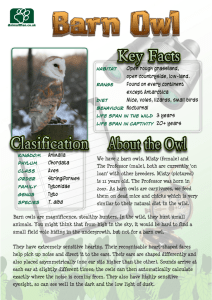

Title: Whoooo knew? Assessment strategies for inquiry science Author(s): Jacque Melin and Ellen Schiller Source: Science and Children. 48.9 (Summer 2011): p31. Document Type: Article Full Text: [ILLUSTRATION OMITTED] Who knew it would happen? Classroom assessment practices have shifted from a focus on checking for students' understanding of memorized material to examining their conceptual understanding as they engage in activities that involve scientific reasoning, inquiry skills, performances, and products. Inquiry-based science has shifted instruction away from teacher-centered, didactic teaching to student-centered, active learning. This shift is naturally accompanied by a need for formative assessment strategies that help students and teachers determine the learning that is occurring along the way. The 5E learning cycle model (Bybee and Landes 1990) embeds assessment throughout the inquiry process: * Eliciting prior knowledge before a lesson or unit, * Checking for understanding throughout the unit, and * Conducting summative assessment at the end of a unit to determine student learning. Standardized summative assessment continues to garner the most attention, but science teachers know that it's critical to effectively evaluate student understanding during inquiry-based learning. In this article we discuss several assessment strategies that you can use and adapt for inquiry-based science units, using the example of a weeklong fifth-grade unit about owls and owl pellets. These strategies, appropriate for middle to upper-elementary level students, actively involve students and provide them with the opportunity to self-assess their own learning. [FIGURE 1 OMITTED] Teachers need to check for understanding and offer feedback in every phase of the learning cycle so that students can conduct sound investigations, draw useful conclusions, and fully develop scientific ideas. To give effective feedback, all assessments should focus on predetermined learning targets. The results will supply information about how well each student understands science concepts and how effectively they use scientific process skills such as observing, interpreting, and communicating (Institute for Inquiry 2010). Correlating Standards Dissecting owl pellets is a common inquiry activity in elementary classrooms. Students enjoy pulling apart the pellets to discover what the owl ate. Purchase commercially sterilized owl pellets and closely supervise students when using forceps or dissecting probes. We have found that plastic forceps work best, and dissecting needles are unnecessary. Students who are asthmatic or highly allergic to animal hair may need to be excused from dissecting real pellets. Pellets, Inc., offers the faux Perfect Pellet as an alternative (see Internet Resources). Students could also engage in virtual pellet dissection, which is a great follow-up extension for all pellet dissectors. Another typical follow-up task is to sort and identify the rodent bones found in the pellets. Often this is done as "stand alone" activity, but owl pellet dissection can launch a full-fledged unit addressing learning targets related to food chains, food webs, animal adaptations, and predator/prey relationships. Assessments that link directly to the learning targets play a key role in any unit. When developing sound assessments, begin by identifying clear statements of intended learning. These statements start with the science standards, but then the standards must be "deconstructed" and written as learning targets (i.e., objectives or goals) that can be shared with your students. Targets should be converted into studentfriendly language through the use of "I can" statements. Shirley Clarke, a British teacher and author, recommends that "I can" statements be written to describe how well students have learned the targets and that they should be posted, not just shared verbally (Stiggins et al. 2009). For our unit on owls, we deconstructed the relevant life science National Science Education Standards to determine our learning targets. Life Science Content Standard C, "The characteristics of organisms" is adapted into the "I can" statement: "I can describe the unique physical and behavioral characteristics of an owl." We address the following physical characteristics of owls: eyesight, hearing, silent flight, talons, beaks, and diet, as well as the owl's behavioral characteristics. Figure 1 shows how the learning targets were shared with students in this unit. Students were given individual copies of the targets and colored in each section of the owl as they demonstrated their mastery. Making targets clear to students at the outset of a unit is the most important foundation to any assessment practice. Throughout the 5E model, students are engaged in hands-on explorations, investigations, and research, from which the teacher helps facilitate scientific understandings and explanations. As the teacher's role changes to one of facilitator, it's imperative that students understand the intended learning targets. Each of the assessment strategies shared in this article involve active student involvement and reflection on the learning targets. Diagnostic Preassessments Before beginning any science unit, it's important to engage students and elicit prior knowledge and possible misconceptions. Anticipation guides are a good method. Focused on key learning targets, anticipation guides list 1-6 true and false statements for grades 4-6 (1-4 statements for primary grades, 4-6 for upper elementary). Lead your students through a discussion of the statements, having them share their rationale, prior knowledge, or current thinking about each statement before marking their predictions. You can use the predictions and discussion as tools for planning and revising unit lessons. After the learning targets have been taught, revisit the anticipation guide with your students and together check off which statements were true and false. Although anticipation guides can also be completed individually via paper and pencil, we've found that the rich discussion that results when leading your whole class through the guide is more effective. Students enjoy sharing their opinions, background knowledge, and thought processes, along with casting their prediction votes and seeing whether they can convince classmates to vote their way. Figure 3. Think dots. Directions: Pairs of students are given a "think dot" sheet and a die. They take turns rolling the die to come up with a number that corresponds to a cell on the think dot sheet. For example, the first student rolls #3. The pair of students then discusses #3 (silent flight), including what they have learned about the physical appearance of the feathers and wings of the owl and how these characteristics help it to hunt prey at night. Each student then records this information in his or her science journal. Next, the second student rolls the die and the pair follows the same procedure for a new number on the think dot sheet. Students continue to roll the die and report on their understanding until all six physical and behavioral adaptations are discussed and recorded. The teacher can collect the science journals and check for students' understanding of the physical characteristics of the owl. Learning Target: I can explain the unique physical and behavioral characteristics of an owl. [ILLUSTRATION OMITTED] Anticipation Guide Figure 2 (p. 33) lists six sample statements about owls, all of which focus on the "big picture" unit learning targets. Make a copy to display on your document camera or overhead projector. Share with students that the anticipation guide lists six statements, some of which are true and some of which are false. Let them know that, during the inquiry unit, they will learn which are true or false through hands-on investigation, research, reading, and video clips (see Internet Resources). Next, read aloud each statement, allowing time for students to share their thoughts and predictions after each one. Although some students will share misconceptions, avoid commenting on students' ideas or sharing "correct" information at this early stage of the unit. We've found that students are more willing to share as the school year progresses, especially if you've created a risk-free learning community in which respect is given to students when they share ideas and questions with each other. After enough discussion time has passed for each statement (3-5 minutes is usually sufficient), take a vote and record the results on the chart. Students will now be engaged in the unit, ready to learn and find out whether they were right in their predictions. We have used this anticipation guide many times and have found that it provides a great springboard to a unit on owls and predator/prey relationships. Note that the statements are written in "kid friendly" language to help engage students. The statements also include some qualifying adjectives and adverbs, such as strictly and all; we've found that this helps to ensure a thoughtful discussion. At first blush, students may think that owls are nocturnal, but adding the qualifier all makes them think: are all owls nocturnal, or are there exceptions to this commonly held belief? When constructing anticipation guides, it's also important to write statements that avoid trivial details. No one will know how many bones an owl has. Stick to the big picture learning targets and concepts. Embedded Formative Assessments Formative assessment that is embedded throughout the unit gives you valuable feedback about students' learning along the way. It allows you to intervene with struggling students, provide challenges for those who are ready, and adapt future lessons for more widespread achievement. Formative assessment also helps students monitor their own learning. Think Dots The "think dot" activity shown in Figure 3 could be used to help students share what they have learned about the unique physical and behavioral adaptations that allow nocturnal owls to hunt in darkness. Students enjoy the novelty of this activity as they formatively assess their understanding. Students report that they benefit from an activity that involves working with a partner to discuss and compare answers. They also like using the die, which makes this assessment more tactile. Formative and Summative Assessments Carol Ann Tomlinson (2006), an expert in differentiated instruction, states that assessments can be differentiated based on readiness, interest, and learning profile. However, it's critical that all variations of an assessment allow students to demonstrate what they've learned in reference to the learning targets. Show and Tell Board We created a show and tell board (Figure 4) for use as a differentiated summative assessment for some of the targets in this unit (Heacox 2009). Even though they have a choice of product, each student shows and tells what he or she knows about the same learning targets. After they read the task, students select a "show" from the top row of the show and tell board and a "tell" from the bottom row. For example, a student might choose to do a PowerPoint presentation to show the food web and write detailed sentences to explain (tell) the flow of energy. Rubric The most common way to judge performance-based responses is through the use of a rubric. When designing rubrics, it's important to stay true to the learning targets being assessed. (Note that on the rubric in Figure 5 (p. 36), only the learning targets are scored.) Rubrics should be written in student-friendly language and help students understand what they must do to achieve a top-level score for a given target. Omit all trivial or unrelated features; things like neatness, attractiveness, color, artistic talent, effort, or design should not be included. You could give your students "work habits" feedback on these elements, but they should not be scored. If you are interested in developing your own rubrics, see Internet Resources. RAFT and Think-Tac-Toe Other types of differentiated choice activities that could be used as either formative or summative assessments include RAFTs or think-tac-toe boards. A RAFT is an engaging strategy that encourages writing across the curriculum. It provides a way for teachers to encourage students to: * Assume a Role. * Consider their Audience. * Write in a particular Format. * Examine a Topic from a relevant perspective. An example RAFT writing choice board that could be used as an alternative to the show and tell board is shown in Figure 6. In this case, student choice is given through a choice of format used. Think-tac-toe choice boards play off the familiar childhood game. Typically, a thinktac-toe grid has nine cells in it like the tic-tac-toe game. Each cell contains alternative ways for students to express key ideas and key skills. It's important that no matter which choices students make, they must grapple with the key ideas and use the key skills central to the topic or area of study (Tomlinson 2003). In most cases, students choose to do three of the activities and form a tic-tac-toe (down, across, or diagonally). An example is shown in Figure 7 of a think-tac-toe choice board that could be used as a formative assessment to determine what students know about the physical and behavioral characteristics of owls. This think-tac-toe choice board could be used as an ongoing formative assessment throughout the unit on owls. We've found that students are motivated by this differentiated assessment because they really enjoy having different product choices as they show us what they've learned. Conclusion Whether you are seeking to maximize learning while dissecting owl pellets, or searching for new ways to integrate effective assessment practices into your teaching, we hope these strategies will be valuable to you and your students as you use assessment to determine "Whoooo knew?" Connecting to the Standards This article relates to the following National Science Education Standards (NRC 1996): Content Standards Standard C: Life Science Grades K-4 * The characteristics of organisms * Organisms and environments Grades 5-8 * Structure and function in living systems * Regulation and behavior * Populations and ecosystems * Diversity and adaptations of organisms Teaching Standards Standard A: Teachers of science plan an inquiry-based science program for their students. National Research Council (NRC). 1996. National science education standards. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. References Bybee, R., and N.M. Landes. 1990. Science for life and living: An elementary school science program from Biological Sciences Curriculum Study. The American Biology Teacher 52(2): 92-98. Heacox, D. 2009. Making differentiation a habit: How to ensure success in academically diverse classrooms. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Press. Institute for Inquiry. 2010. "Workshop 1: Introduction to Formative Assessment." Accessed December 8. www.exploratorium.edu/ifi. Stiggins, RJ., J. Arter, J. Chappuis, and S. Chappuis. 2009. Classroom assessment for student learning: Doing it right-using it well. Portland, OR: Assessment Training Institute. Tomlinson, C.A. 2003. Fulfilling the promise of the differentiated classroom: Strategies and tools for responsive teaching. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Tomlinson, C.A., and J. McTighe. 2006. Integrating differentiated instruction and understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Internet Resources Kidwings www.kidwings.com Owl Cam www.owlcam.com Pellets, Incorporated www.pelletsinc.com Rubistar www.rubistar.com Whoooo Knew www.whooooknew.com Ellen Schiller (schillee@gvsu.edu) is an Associate Professor and Jacque Melin is an Affiliate Professor, both in the College of Education at Grand Valley State University in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Figure 2. Anticipation guide. Prediction Statement Agree Disagree 1. Owls have an excellent sense of smell, which helps them locate prey in darkness. 2. Owl pellets are owl poop. 3. Owls are strictly carnivorous. 4. All species of owls are nocturnal. 5. Adult owls have few natural predators. 6. It is a federal crime to intentionally injure or kill an owl. Note. For the answer key, visit www.nsta.org/SC1107. Figure 4. Show and tell board. Learning Targets: Findings True False I can classify the role of each organism in the food web of an owl. I can explain the energy flow in the food web of an owl. Task: Construct a food web with the owl at the highest trophic level. Be sure to include producers (green plants) and decomposers in your food web. Also include the Sun. The intermediate organisms should include the prey found in the owl pellets that you dissected in class. Label the role of all organisms and use arrows to show the energy flow between each organism. Finally, explain the flow of energy in the food web. SHOW Draw a poster showing a food web with the owl at the highest trophic level. Label the role of all organisms (consumer, producer, decomposer). Use arrows to show the energy flow between each organism. Create a PowerPoint presentation showing a food web with the owl at the highest trophic level. Label the role of all organisms (consumer, producer, decomposer). Use arrows to show the energy flow between each organism. Design a brochure showing a food web with the owl at the highest trophic level. Label the role of all organisms (consumer, producer, decomposer). Use arrows to show the energy flow between each organism. TELL Explain the energy flow in the food web by writing a descriptive paragraph. Explain the energy flow in the food web by writing a story. Explain the energy flow in the food web by writing detailed sentences. Figure 5. Show and tell board rubric. Target 5 3 1 I can classify the role of each organism in the food web. I have accurately illustrated and classified all of the organisms as either consumer, producer, or decomposer in the food web. I have accurately illustrated and classified some of the organisms as either consumer, producer, or decomposer in the food web. I have accurately illustrated and classified very few of the organisms as either consumer, producer, or decomposer in the food web. I can explain the energy flow in the food web of an owl. I have pointed all arrows in the correct direction of the energy flow and have accurately I have pointed some of the arrows in the correct direction of the energy flow and partially I have pointed a few of the arrows in the correct direction of the energy flow and have not described the flow of energy in the food web. described the flow of energy in the food web. described the flow of energy in the food web. Figure 6. RAFT writing choice board. Directions: You will take on the role of an owl, explaining the owl's food web and how it connects to the owl's diet (topic), to prey (the audience). You have a choice of formats. Please see the RAFT choice board below. Role Audience Formats (choices) Topic Owl Prey * a 3-minute speech with visual aides * a flowchart * an important e-mail * an interview between an "owl" and "prey" * a newspaper story Explain my food web and how it connects to my diet. Figure 7. Think-tac-toe choice board. Directions: Choose three activities in a row (down, across, or diagonally) to form a tic-tic-toe. For each choice, select a different physical or behavioral characteristic (eyesight, hearing, silent flight, talons & beak, behavior, diet). Create a game for learning about the importance of one of the physical or behavioral characteristics of owls. Create a PowerPoint presentation that could be used to teach students about the importance of one of the physical or behavioral characteristics of owls. Write and recite a poem that shows the importance of one of the physical or behavioral characteristics of owls. Make a flow chart to summarize important information about one of the physical or behavioral characteristics of owls. Write an essay about the importance of one of the physical or behavioral characteristics of owls. Plan and present a debate about which one of the physical or behavioral characteristics of owls is most important. Note: you may work on this with a partner; each take a different side of the debate. Write and present an advertisement explaining which one of the physical or Write and perform a song or rap about the importance of one of the physical or Write and illustrate a children's book explaining the importance of one of behavioral characteristics of owls is most important. behavioral characteristics of owls. the physical or behavioral characteristics of owls. Schiller, Ellen^Melin, Jacque Source Citation (MLA 7th Edition) Melin, Jacque, and Ellen Schiller. "Whoooo knew? Assessment strategies for inquiry science." Science and Children Summer 2011: 31. Academic OneFile. Web. 25 Sep. 2012. Document URL http://proxy.buffalostate.edu:2128/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA270896139&v=2.1&u=buf falostate&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w Gale Document Number: GALE|A270896139