Romantic Quests vs. New Criticism

advertisement

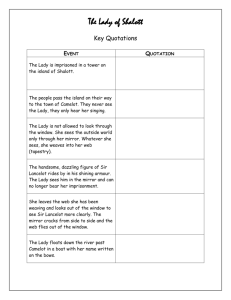

Romantic Quests vs. New Criticism Wordsworth, Keats, Tennyson and Felicia Hemans Outline Starting Questions & Romantic Quest Defined “Tinturn Abbey” & Wordsworth John Keats & “La Belle Dame Sans Merci”; the images Tennyson & “The Lady of Shalott” New Criticism Keats and New Criticism – “Ode on Melancholy” as an example Felicia Hemans Starting Questions What do you think about the poems you’ve read (“Tinturn Abbey” “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” “Lady of Shalott”)? Do you appreciate their concerns or find them boring? What does “Quest” mean? Are you in any kind of quest? Romantic Quests The Sublime; Transcending the “human” Truth –in Nature, Democracy Beauty Art Women, Nature, Medievalism Romanticism Defined The poets Wordsworth’s “Tinturn Abbey” What is it about? How is this poem similar to “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”? To understand the poem, you need to 1) pay attention to changes of tenses; 2) Syntax (where subjects and verbs are) and conjunctions (e.g. such as, so that, nor) reading Cliffs Visualization Visualization Cottages, Orchards, Hedgerow “Tinturn Abbey”: Structure 1. Re-Visiting 2. The influences of memories of the natural scenes; --from sensations to vision on life; 3. Addressing the Wye river; 4. Back to the present moment, to think over the future and the past. 5. Turn to his sister, to find hope in his sister and to strengthen her against future decay. Wordsworth’s “Tinturn Abbey” 1. Pay attention to the many repetitions in this poem. Do they correspond to the content of the poem? Are there beautiful lines in this poem? 2. What do you think about the speaker’s views of 1) nature’s influence on us (ll. 122-134), and 2) our different experiences of nature at different ages of our lives (stanza 3)? 3. What role does the sister play in this poem? Wordsworth’s Quests in “Tinturn Abbey” Functions of repetition – 1) (once again, how oft, ) to show changes; – 2) (in which, in thy voice, so … so…) to reinforce his beliefs – 3) alternates with the vivid descriptions. Attempts to deal with aging, losses and even death. Seeks comfort in nature, but ultimately in the sister’s remembering him. In this way, ‘Nature’ is finally displaced. Actually, there are more displacements in this poem. “Tinturn Abbey” in Context French revolution in 1789, which inspired Wordsworth to visit France in 1791. He returned in despair in 1792. Two visits 1793 & 1798: W’s trip to Salisbury Plain and North Wales in the summer of 1793, and his return visit particularly to the abbey, on July 13, 1798. 1793 – the publication of his first poems. 1798 – the conception of the idea for Lyrical Ballads and then its publication. The poem, in this sense, is an important example of his poetic quest (for Nature or for Poetic Self). Wordsworth & “Tinturn Abbey” In the poem not a word is said about – the French Revolution, the impoverished and country poor, or—least of all—that this event and these conditions might be structurally related to each other. (J. McGann 85-86) Tinturn Abbey in 1790s A favorite haunt of transients and displaced persons—of beggars and vagrants of various sorts, including “female vagrants.” Wordsworth observes the tranquil orderliness of the nearby “pastoral farms” and draws these views into a relation with the “vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods” of the abbey. The poem’s method: to replace an image and landscape of contradiction with one dominated by “the power/Of harmoney”; or a picture of the mind. John Keats (1795-1821 age 26) His poetic quest is both difficult and brief. Family: His father died in a riding accident; his mother involved in a lawsuit against her own mother over inheritance. Keats nursed her mother when she was ill with T.B., and, later, his brother with T.B. Then finally he contracted the disease. clip on Keats John Keats (1795-1821 age 26) 1810 -- Keats started out as an apprentice to an apothecary (pharmacist). 1813 -- He was inspired by Spenser and Homer. 1816 – promoted to assistant surgeon but also started to publish his poems. 1817 – publishes his first book; met Wordsworth, but didn't like him. 1818 – nursed his brother; met Fanny Browne 1819 – The Great Odes, and several other poems. Engaged to Fanny Brown; Fell ill. Keats: Main Concerns in his Poetic Quest Truth and Beauty vs. Mortality (“vale of soul-making”) Intense but Transient Sensual Pleasures in Nature He is always keenly aware of, or even relishes, the possible contradictions. “La Belle Dame” reading 1. Plot & Theme: Is the woman real or not? What does she represent? Can you think of any similar experience to this? In other words, can the woman be symbolic of some ideal you pursue? 2. Plot & Theme: What are the functions of the dream(s)? 3. Structure: Beginning, middle and end? 4. Narration/Narrative Frames: Why doesn’t the knight tell the story to us directly in a first-person narrative? Why is there another speaker in the poem? What does this speaker add to the poem? “La Belle Dame sans Merci?” Theme: Unrequited love, or obsession in an impossible quest? – The woman – beautiful and weak, to be protected and decorated, love,. – Impossible quest – offers sweetness & love; a fairy’s child; ‘as’ she did love; strange language; sigh full sore. ‘sweet moan’? Images of la Belle Dame John William Waterhouse The latter painting reveals Waterhouse's growing interest in themes associated with the PreRaphaelites, particularly tragic or powerful femmes fatales. Images of la Belle Dame Left: Sir Frank Dicksee (British, 1853-1928) Right: Arthur Hughes (British, 18321915) Pre-Raphaelite Painter. Images of la Belle Dame Frank Cadogan Cowper, the last of the Pre-Raphaelites “La Belle Dame”: theme & structure The ‘latest’ dream –not the only dream, not only dreamed by him. The stranger– describes the knight as well as the environment, thus provides a sense of reality (which can be abundant). “La Belle Dame” vs. traditional ballads Traditional ballads (“Thomas the Rhymer”): lack of self-consciousness. Keats: estranged persons—the knight by virtue of his experience with the elfin lady, and the balladeer by virtue of his narration of that experience. the irrevocable loss of an entire area of significant human experience as well as its meaning. Tennyson Representative of the Victorian views of literature/art’s social functions. “The Lady of Shalott” significance: – –reflects “The Woman’s Question” – Two versions: 1833 and 1842 – The most favoured of all Tennysonian subjects among the PRB. Question I: what is the story about and how does the form help convey its meaning? “The Lady of Shalott” 1. Structure: Part 1 – 1) Setting: the river & the fields, the road and the island; 2) Lady of Shalott observed and listened to; 3) Form: alternation of short and long lines. Part 2 – Shalott in her tower, weaving and looking at the shadows on the mirror; sick when seeing funeral procession or lovers pass by. Form: long lines with mellifluous sounds. “The Lady of Shalott” 1. Structure: Part 3 –Lancelot passes by and Shalott turns to see him. Form: explosives + alliteration; images of light; ends with rep. of ‘she’ in action. Part 4 – Shalott leaves her tower to go to Camelot. Action (writing her name and singing). Form: explosives + mellifluous sounds and feminine rhymes. “The Lady of Shalott” 1. Theme: What can the mirror be symbolic of? What does the lady want? 2. Does it matter why we don’t know why the lady is cursed? 3. There are two versions of this poem: 1833 and 1842 versions. Compare the endings of these two versions. 4. Compare this poem with “La Belle Dame” by Keats. What aspects of Quest are presented in these two poems? Does gender make a difference here? “The Lady of Shalott” 1833 version: the ending. They cross’d themselves, their stars they blest, Knight, minstrel, abbot, squire, and guest. There lay a parchment on her breast, That puzzled more than all the rest, The wellfed wits at Camelot. ’The web was woven curiously, The charm is broken utterly, Draw near and fear not,--this is I, The Lady of Shalott.’ Images of Shalott William Holman Hunt, The Lady of Shalott, allegorical elements: Please pay attention to the wall's dark tapestries, "upon which swirl the twisting bodies of angelic and allegorical figures, while the two roundels supporting the great mirror feature scenes of the Fall and the nativity [Wadsworth]" (Pearce 79) exotic elements: sandals & samovars (Russian urn) Images of Shalott William Holman Hunt, The Lady of Shalott, Images of Shalott Elizabeth Siddal, The Lady of Shalott Images of Shalott Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Lady of Shallott, 1857 Wood engraving, 35/16 x 31/16 in. Victoria and Albert Museum, London New Criticism: Methodology (1) Poetry Parts Figurative Language Denotations, connotations and etymological roots Allusions Prosody Relationships among the various elements Whole Themes pattern, tension, ambiguities, paradox, contradictions New Criticism: Methodology (2) Narrative Parts Narrator (Point of view), dialogue, setting, Plot Characterization Relationships among the various elements Whole Themes harmonized pattern, tension, ambiguities, paradox, contradictions John Keats -- & the New Critics T.S. Eliot cited “Ode to a Nightingale” a case of “impersonal” art that he elevated over the Wordsworthian effect of expressing a “personality.” Keats: poet as camelian Wordsworth—egotistical sublime; Keats: negative capability (an ability to negate self-interest) The Great Odes – “integration of intellect and emotion”; form and content. Ode on Melancholy Note: To the Romantics, the word no longer signified a state of clinical gloominess, strangeness, and solitary wanderings. It implied a positive, heightened sensibility which could, of course, bring inspiration to the artist. Ode on Melancholy 3 parts Part I: Do not use drugs or poison (traditional symbols of death & melancholy) to ease your pains; Part II: Rather savor melancholy to the fullest (through appreciating transient natural beauties or the mistress’s anger). Part III. Because melancholy is inseparable from transient beauty, joy, painful pleasure, appreciated only by the one with fine palate. Ode on Melancholy Paradoxes 1. Negative imperative + active verbs; “active pursuit” of these easy means of escape will, in the end, get the soul ‘drowned.’ 2. Paradox of birth+ death; beauty + transience; observation + eating; 3. Active pursuit of pleasures and pains turns the poet into something passive. Keats’ Odes in the Eyes of New Critics & Deconstructionist Its density suitable for close analysis; “a totalizing principle as the guiding impulse” Ironies—” a discontinuous world of reflective irony and ambiguity” Paul De Man: “Almost in spite of itself, this unitarian criticism finally becomes a criticism of ambiguity, an ironic reflection of the absence of the unity it has postulated.” (Wolfson 191-92) Keats’ Odes in the Eyes of New Critics & Deconstructionist Example: ‘Ode to a Nightingale’—an organic form, a unity encompassing the ‘interrelation’ of its parts, its ‘formal elements’ and its subject. (Brooks) “a turmoil” of “disintegration” (Wasserman) Keats’ Odes – engagement with “a state of perpetual indeterminacy” Women’s Roles in Romantic Quests? Felicia Hemans -- seen as angel by her contemporaries “She seems to me to represent and unite as purely and completely as any other writer in our literature the peculiar and specific qualities of the female mind. . . The delicacy, the softness, the pureness, the quick observant vision, the ready sensibility, the devotedness, the faith of woman's nature” (source: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/hemans/rfhemans.html ) -- Poetess, whose duties are to sing of domestic bliss e.g. “The Homes of England” -- exception “Casabianca” Note: Romanticism A movement in art and literature in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in revolt against the Neoclassicism of the previous centuries… . . Imagination, emotion, and freedom are certainly the focal points of romanticism. Any list of particular characteristics of the literature of romanticism includes subjectivity and an emphasis on individualism; spontaneity; freedom from rules; solitary life rather than life in society; the beliefs that imagination is superior to reason and devotion to beauty; love of and worship of nature; and fascination with the past, especially the myths and mysticism of the middle ages. (source: http://www.uh.edu/engines/romanticism/ ) Back Outline References Walfson, Susan J. Formal Charges: The Shaping of Poetry in British Romanticism. Stanford 1997. McGann, Jerome. The Romantic Ideology: A Critical Investigation. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1983. Pearce, Lynn. Women/Image/Text. London: Harvester/Wheatsheaf, 1991. Images of “La Belle Dame Sans Meric” http://www.artmagick.com/themes/theme4.aspx