Diapositiva 1

advertisement

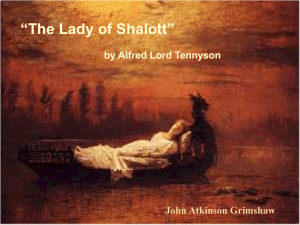

Victorian Poetry? All novels are destined to disappear within a generation. Whereas poetry is about eternal passions, modern novelists depend on the their readership and should therefore be regarded suspiciously. (Thomas de Quincey, author, and essayist, journalist, 1848) The great English novelists are Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James, and Joseph Conrad. [...] Critics have found me narrow [...] I hold that since Donne , there is not poet we need bother about except Hopkins and Eliot. (F.R. Leavis, The Great Tradition, 1948) Can literature be judged in an objective way? Is the literary canon stable? Who decides what is good/bad literature and high/low literature? Marxist and Feminist criticism and, more recently, Cultural Studies have challenged the idea of a ‘Western Canon’ and have tried to enlarge it. One of their ‘heroes’ is Antonio Gramsci, who believed there is always an ideology involved in canon formation. Remember the passage from Byatt: ‘La Motte? Oh Yes, Melusina. There was a feminist sit-in, in the Fall of ‘79, demanding that the poem be taught in my nineteenthcentury course instead of Idylls of the King or Ragnarok. As I remembered it was conceded. But then Women’s Studies took it on, so I was released and we were able to restore Ragnarok.’ (Cropper speaking, Possession, p. 305) On Victorian poets... ‘They thought of themselves as modern. Victorian modernism sees itself as new but it does not, like twentiethcentury modernism, conceive itself in terms of a radical break with the past.’ (Isobel Armstrong, Victorian Poetry, 1996, p.3) In an interview A.S. Byatt said: ‘The Victorians were not simply Victorian. They read their past and resuscitated it’ The Victorian look on the past and the narrative and theatrical dimensions of Victorian poetry are the aspects we are going to investigate in the next classes. Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) Poet Laureate to Queen Victoria from 1850 to his death. He started writing poetry as a child and was a big fan of Lord Byron. He has been defined conservative, reactionary, evasive. The Idylls of the King is the title of his famous reworking of the stories of king Arthur and his knights: the work was composed and published between 1856 and 1885 and it is madenof twelve narrative poems. The Lady of Shalott is a juvenile poem, and it was published in two versions, in 1833 and 1842. Sources: Arthurian stories of Elaine found in: Malory’s Morte Darthur (editio princeps 1485) The Stanzaic Morte Arthure (fourteenth century) and La Donna di Scalotta, a nineteenth-century Italian novella However, the poem is a very personal reworking of this material. The Lady of Shalott is a literary ballad. What formal characteristics make it so? What can you say about the language? What can you say about sounds patterns? Illustration of Tennyson’s poem by Howard Pyle, 1881. How is the story told and the characters described? What about the setting? William Holman Hunt Illustration for the Moxon edition of Tennyson Poems, 1857 John William Waterhouse 1894 John William Waterhouse ‘I am half-sick of shadows’ 1916 William Maw Egley, 1858 John William Waterhouse, 1888 Arthur Hughes, ‘The Lady of Shalott’, 1873 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, illustration for the Moxon edition, 1857 Why the Middle Ages? ‘Popular antiquarianism, and the romances of Sir Walter Scott, had enabled readers for the first time to imagine a DISTANT HISTORICAL PAST neither classical nor biblical but PART OF NATIONAL HISTORY, and to engage with an open mind in an imaginative comparison of such a past with the present state of society’ (Michael Alexander, Medievalism, 2007, pp. 84-85) Nineteenth-Century Medievalism Religion: Attempt to revive the Sacramental religion of the Middle Ages (Cardinal Newman) Social Reform: Dignity of individual work Rural vs industrial life Thomas Carlyle John Ruskin Arts and Decoration: Architecture (A. W. Pugin) Medieval festivals and tournaments Pre-Raphaelites Arts and Crafts Movement Thomas Carlyle A famous excerpt from Past and Present (1834) where he speaks about Gurth, a character from Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. Gurth was a swineherd and he was a thrall (slave). Gurth, born thrall to Cederic the Saxon, has been greatly pitied. [..] Gurth, with the brass collar round his neck, tending Cederic’s pigs in the glades of the wood, is not what I call and exemplar of human felicity: but Gurth, with the sky above him, with the free air and tinted boscage and umbrage round him, and in him at least the certainty of supper and social lodging when he came home; Gurth to me seems happy, in comparison with many a Lancashire and Buckinghamshire man of these days, not born thrall of anybody! [...] Gurth had superiors, inferiors, equals. – Gurth is now ‘emancipated’ long since; has what we call ‘Liberty’. Liberty, I am told, is a divine thing. Liberty when it becomes the ‘Liberty to die by starvation’ is not so divine! Tennyson’s poetry feeds on the medieval past, but also on biblical and classical stories. The Lady of Shalott is a reworking of other stories and myths: Elaine of the Arthurian tradition The Lady of Scalot in the Italian novella Arachne Penelope Narcissus Lot’s wife However, the result is original and it includes the two aspects of Tennyson’s poetry: the ‘romantic’ (i.e. idealistic, derived from high romance) and the social.: Words like WEAVE LOOM REAPERS Could not but remind the Victorian readers of their present. Power-Looms Newspaper illustrations Nineteenth-century workers in Lancashire: Queuing for food Child Labour Protest We can look at the poem in at least two ways: FIRST LEVEL = OPPOSITIONAL READING RURAL vs URBAN LABOUR BY HAND vs MERCANTILISM ORGANIC/INTEGRATED WORLD vs FRAGMENTED COMMERCIAL WORLD ISOLATION vs COMMUNITY PASSIVITY vs ACTION FEMALE vs MALE THE AESTHETIC vs THE REAL This reading condemns the protagonist to PASSIVITY or DEATH. However, other, less apparent, readings are possible. Think about the opposition appearance/reality: -Images from outside are reflected in the mirror and they are weaved into the magic web: reality is seen through a mirror and through the lens of art However, -The world outside the tower is equally a confusion of reflection, image, and figure. Think about how the image of Lancelot reaches her: ‘From the bank and from the river He flash’d into the crystal mirror’ Think about The Lady of Shalott and Labour: there are several layers of meaning at work at the same time. - She is a weaver and she delights in her art (She can be seen as a symbol of pre-industrial home-weaving) - She weaves ‘by night and day’; she weaves ‘steadily’; ‘she didn’t choose it, she must keep her position within the room, etc. (she can be seen as an alienated industrial worker) The same can be said about farming: - The landscape is beautiful and bucolic, or rather ‘idyllic’ - The reapers are ‘weary’, exhausted because of work Think of the poem in terms of LACK: could it be a celebration of awareness rather than passivity? Isobel Armstrong thinks so: ‘The reapers and the Cambridge rick-burners reacting to the Corn Laws, the starving handloom weavers who were being displaced by new industrial processes, these hover just outside the poem and become strangely aligned with the imprisoned lady. The possibility of change is explored through her psyche, as she becomes a representation of alienation and work. She is unaware of the constraints worked upon her and obedient to the mysterious power until the appearance of lovers in the mirror forces her to reconceptualise her world as phantasmal and secondary, mere representation. [...] The culminating sense of Lack brings the lady into action. [...] What was lacking was the sense of lack which forces a realisation of estrangement and oppression. The curse is the myth of power, a representation, which kept the lady subject.’ (Victorian Poetry, 1996, 84-85) The position of the poet remains problematic, though. The poem has always been read as a celebration of artistic isolation. Tennyson revisits the Romantic rejection of vis-àvis confrontation with external reality, better expressed in John Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale: “ […] for many a time I have been half in love with easeful death” (1819) However, the position of the poet could also be read in the terms proposed by Armstrong, as the Lady does leave her art and go out into ‘Nature, red in tooth and claw’ (Tennyson, In Memoriam). We could think about the words of Ash in Possession: ‘Could the Lady of Shalott have written Melusina in her barred and moated tower?’ (p. 188) The Lady of Shalott was the subjects of many paintings , but it also inspired the visual culture of the day in many ways... John Tenniel, The Haunted Lady, or “The Ghost” in the Looking Glass, 1863 Nineteenth-century seamstresses 'The Lady of Shalott' by Elizabeth Siddal The Lady of Shalott was set to music by the Canadian singer Loreena McKennitt in 1991. It is worth listening to it to have a taste of what it means to listen to -- as opposed to read -- a ballad. You can listen to it on Youtube (for example at http://www.youtube.com /watch?v=ttv0ljOiPSs&feature=related) and you can also have an idea of the popularity the poem still enjoys and of the (more or less bizarre) uses people have made of it. A literary Italian translation of the poem is online at: http://www.apaxcreativi.ch/Writings/The_Lady_of_Shalott.html A very useful website for original texts and pictures of medieval and medievalist Arthurian material is that of the Camelot Project at the University of Rochester: The editors are among the leading Arthurian scholars of our times: http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/cphome.stm