The deepening of European integration: the Treaties

advertisement

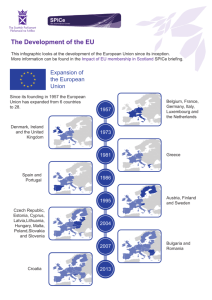

EU-integration knowledges 1st Semester, Academic Year 2010/2011 Written by Endre Domonkos I. The notion of Treaties Enlargement means the admission of new member states. Deepening means the intensification of collaboration (qualitative changement in the integration) and the expansion to other fields. Both of the above mentioned notions are in mutual interaction but aren’t realized at the same time. We can examine the development of the stages of integration process through the different Treaties and their amendments. Among the legal sources, the Treaty on European Union and the three Treaties establishing the Communities, as well as subsequent amendments, occupy a central role. Collectively known as the „Treaties” they established the institutions of European integration and provided basis for the operation of the EU. Treaties are always the products of the so-called Intergovernmental Conferences (IGCs) among the governments of the Member States. IGCs can be considered as traditional, diplomatic negotiations, where all the Member States are present as sovereign powers. As result, all decisions must be reached with the agreement of all parties (consensus). Any treaty emerging as a result of an IGC must always be ratified by all signatories, in accordance with their own internal constitutional requirements. A treaty will not enter into force until ratified by all parties. Any amendment of the Treaties must also be agreed to an IGC and ratified by the Member States. II. The concept of the „Treaty” and „the Treaties” I. The European Union was founded on four Treaties. The three Community Treaties, establishing the European Community (EC) (formerly known as the European Economic Community), the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), as well as Treaty on European Union. It should be noted that the ECSC Treaty expired on 23 July 2002, having only been concluded for 50 years. Therefore, only three treaties remain in force, but they were concluded for an indeterminate period. Despite the expiry of the ECSC Treaty, its provisions ‘live on’ within the EC due to the general common market effect of the EC Treaty. The financial implications of the expiry of the ECSC Treaty were dealt with in a Protocol annexed to the Treaty of Nice. The previously four, now three treaties, are collectively known as the „Treaties”. „Treaty” always refers to one of the three Treaties. If we use the term „Treaty”, it can refer to the EU Treaty, the EC Treaty or the Euratom Treaty, depending on the context in which the term is used. Without a clear reference, the term „Treaty” refers to EC Treaty in the literature on European integration. A clear definition of the „founding treaties of the European Union is made even more difficult by the numerous amendments made the four Treaties. Founding treaties were amended by various other treaties. Thus these subsequent treaties are not independent instruments; they are only treated as such because of the need to have all Member States sign up. II. The concept of the „Treaty” and „the Treaties” II. The new treaties are merely instruments amending or modifying the first three Treaties (the Treaty of Paris and the two Treaties of Rome) and are not parallel effective instruments. New treaties always overwrite old ones. In other words, the Treaty of Nice is not a treaty in its own right, but an instrument containing amendments to the EC, the Euratom and the EU Treaties. The provisions of the Treaty of Nice are consolidated into these Treaties; the Treaty that has legal force is not the Treaty of Nice but the EC, the Euratom and the EU Treaties, as amended by the Treaty of Nice. The terms „Treaty” and „Treaties” always refer to the amended versions of the old treaties, namely the provisions that are in force at that time. These treaties are published in a consolidated form (Consolidated Treaties), and references are also made to the consolidated text. The Treaty on European Union provides some kind of framework for the relationship between the Treaties. The Treaty on European Union contains provisions concerning the EU as a whole (i.e. all pillars) as well as the second and third pillars. The Treaties establishing the three Communities, together with the amendments, are defined as three separate Titles within the EU Treaty. On 1 December 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force that abolished the three pillar structure introduced by the Treaty of Maastricht. It should be noted that the Treaty of Lisbon amends the current EU and EC treaties, without replacing them. III. The nature of The Treaties: the framework treaty structure Even to this day, the Treaties reflect the system laid down in the Treaty of Paris and the two Treaties of Rome. The aim of the most important treaties, the Treaty of Rome establishing the EEC, was to ensure the free movement of goods, services, labour and capital and to establish a common market, which basically involved the extension of the sectoral integration brought about by the ECSC Treaty to the whole economy. The primary objective of the EEC Treaty was to establish a common market, but not all of its provisions were about the common market. The Treaty of Rome provided for setting up common policies and Community activities and defined economic and social objectives. It did not lay down specific measures but defined tasks and objectives, entrusting the Community institutions and the Member States with their implementation. The Treaty of Rome and its various amendments are like a programme, containing no detailed obligations, but instead offering an opportunity for the elaboration of various policies and the deepening of cooperation and of harmonisation. The policy content of the programme is rather varied: some objectives are fully worked out, together with deadlines, while others are surprisingly general. For this reason, it is not unfair to consider the Treaty of Rome and its amended versions as a framework treaty, in which the contracting parties – the Member States – entrust the institutions of the Community with drawing up the legislation necessary for implementing these principles. The Treaties thus provide a legal point of reference for future Community instruments that are adopted to achieve the objectives. IV. The founding treaties The founding treaties, their amendments and other supplementary treaties based thereon are also known as primary legislation under the framework treaty structure. Primary sources of law, in other words the founding treaties and subsequent amendments, include (the first date the treaty was signed, the second date is when it came into effect): - The Treaty of Paris establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) (18 April 1951; 25 July 1952) - The Treaty of Rome establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) (25 March 1957; 1 January 1958) - The Treaty of Rome establishing the European Atomic Eenergy Community (Euratom) (25 March 1957; 1 January 1958) - The Treaty establishing a Single Council and a Single Commission of the European Communities – Merger Treaty (8 April 1965; 1 July 1967) - The Single European Act (18 February 1986; 1 January 1987) - The Treaty on European Union – Treaty of Maastricht (7 February 1992; 1. November 1993) - The Treaty of Amsterdam (2 October 1997; 1 May 1999) - The Treaty of Nice (26 February 2001; 1 February 2003) - The so-called budgetary Treaties of 1970 and 1975, regulating the budget of the EU and amending the founding treaties, - The Treaties of Accession signed whenever a New Member State is admitted (Denmark, the United Kingdom, Ireland – 1972, Greece -1979, Portugal, Spain – 1985, Austria, Finland, Sweden -1994, Cyprus the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia – 2003, Romania and Bulgaria – 2005, - The Treaty of Lisbon (13 December 2007; 1 December 2009). V. The provisions of the Treaty of Rome The Treaty of Rome that established the EEC, set the establishment of a common market as the overall aim of the Community; The main task of the Treaty was to provide „the harmonious and balanced development of economic activities… raising of the standard of living… economic and social cohesion and solidarity among Member States… through gradual convergence of economic policy (Article 2 of the Treaty). The overall aim was to be achieved by following main specific objectives (Article 3): the elimination of customs duties and quantitative restrictions, and of all other measures having equivalent effect; establishment of a customs union and adherence to a common commercial policy against countries outside the Community; free movement not only for goods and services, but also of labour and capital within the Community; a common policy in the areas of agriculture, transport, and competition; approximation of national laws. The Treaty of Rome that established EURATOM set as one of its aims the quick establishment and development of the atomic energy industry, identifying a number of tasks from common research to the effective utilisation of atomic energy + provision of nuclear safety. Institutional system was also set up by the Treaty of Rome. The Council of Ministers as the main decisionmaking body of the EEC. The Commission became the main initiator of decisions, equipped with some decision-making authorisation. The Assembly had the role of consultation, authorisation and limited supervisory competence. The Court of Justice received the task of interpreting and securing compliance with emerging Community law. The European Social Fund (to promote the employment and increase the living standard of citizens) and the European Investment Bank (to contribute the economic development of Member States) was also established by the Treaty of Rome. VI. The first fifteen years of the EEC On 1 January 1959. According to the dispositions of the Treaty of Rome the removal of customs and quantitative restrictions between the Member States was completed by the middle of 1968. Common customs tariffs were also introduced. In the period between 1958 and 1973, trade between the member countries grew dynamically as a result of trade liberalisation and customs union. Foreign trade produced and annual growth rate of 8 %, annual expansion of trade within the Community achieved a rate of 12 % . The establishment of integration coincided with an economic boom. That period was characterised by fast technical development, radical modernisation of the structure of economy, dynamic expansion of consumption, and an annual 5 % rate of increase in GDP. Inspired by this success, the leaders of the European Community were elaborating plans for reducing monetary union as early as 1969 and 1970. However, the Werner Plan that dealt with the details failed within a short time, due to the financial crisis of the early ’70s and the oil crisis of the same period. While it was easy to introduce the customs union, the free movement of capital and labour appeared hard to implement. Although the general conditions of free movement were liberalised, the pure form of a theoretical common market could not be achieved in practice. In addition, operation of the policies aimed at various specialised community areas (e.g. transport, social matters, etc.) was also in its infancy. VII. The european integration after De Gaulle’s viewpoint In 1962. Working out a common agricultural policy (CAP). Introduction of unified system, unification of the prices of the most important products in the common market, social support for the agricultural sector. Agricultural levies on external import. Supporting the agricultural export from common budget in there the agricultural levies were handed (paying out the differences between the higher internal and lower external prices for the exporters). Direct subsidies were eliminated. On 23 January 1963. Friendship agreement between France and Germany. French and German presidencies meet twice in a year. Competent ministers coordinate their own standpoints in the field of foreign affairs, economy, culture and defence policy. General De Gaulle set a veto on the application when the United Kingdom indicated its intention to join the Community in 1963 and in 1967. The radical approach taken by President De Gaulle considerably affected not only the external relations of the Communities but also the internal functioning of integration. The General proclaimed the idea of the „Europe of Nations” and intended to steer the Communities towards purely intergovernmental cooperation led to serious crisis in 1965 when he boycotted participation in Community institutions for a half year period through his „empty chair” policy because he didn’t agree with the proposals made for financing agricultural policy. On January 1966. Luxembourg compromise (where a Member State declared that its fundamental national interest was at stake in a given situation, a solution could be accepted only if unanimous agreement was reached. VIII. The Merger Treaty and its institutional impact In the mid-sixties, the institutions of the three integration organisations were united. In pursuance of the Merger Treaty, adopted in 1965, the parallel institutions of the ECSC, the EEC and Euratom were merged by July 1967. In addition to the common Court of Justice and the Assembly (which was named as the European Parliament in 1962) of the three Communities, the Commission and the Council were reorganised to serve all three institutions. The High Authority of the ECSC was merged with the Commission. The name European Communities (EC) has been used since that time, although it has be noted that the three communities have preserved their independent international legal status and only their institutions became common institutions. It should be noted that, since the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, the acronym EC has been used to denote the EEC. The Maastricht Treaty renamed the European Economic Community (EEC) as the European Community (EC). Thus, the term EC refers to the former EEC and not the three Communities collectively. As a general rule, when Community is used in the singular form, it is mostly the context that reveals which of the three communities is being referred to. When no explicit reference is made, then the European Economic Community is meant; the ECSC and Euratom are usually referred to through specific reference. In clarifying the scope of competences of the three Communities, it should be pointed out that the EEC (and, since Maastricht, the EC) operates as an organisation with general competence in issues related to the common market, as opposed to the ECSC and Euratom. While the latter two have clearly delineated scopes of activities and fields of application, the EEC Treaty must be applied, as a general rule, in areas not specifically regulated by the ECSC and the Euratom Treaties. IX. The European integration process in the 1970’s I. On 1-2 December 1969. Conference of Hague. Agreement that CAP will be financed from the common budget, starting the accession negotiations with the United Kingdom, Denmark, Ireland and Norway. The candidate countries should accept the acquis communautaire. On the first half of 1970. Common decision about the establishment of Monetary union (Werner Report). Main targets: harmonising the national financial, budgetary , tax policies and exchange rate mechanism, unification of national reserves, and introduction of single currency in three stages). On March 1972. Six Member States decided to keep their Exchange Rate Mechanism within ± 2,25 % of the rates. On 1 January 1973. Denmark, Ireland and United Kingdom became the members of the European Communities. The world oil shock triggered by the Arab-Israeli triggered by the Arab-Israeli War of 1973 - which was further aggravated by the earlier collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 – had a rather negative impact and hindered futher integration considerably. As a result of the crisis and, basically, the increase of oil prices, together with the related growth in proportion of the oil trade, trade within the Community was affected the most. As a consequence of prolonged crises, the Member States introduced protectionist measures, which presented an obstacle to closer integration and the realisation of a fully-fledged common market. On the other hand, mutual dependence within the Community increased even more this period. Relations between the Member States became more and more intensive in terms of micro- and macro-economics. IX. The European integration process in the 1970’s II. A common commercial policy had been fully implemented by the mid-seventies, which resulted in a more uniform economic an trade attitude amongst the Member States towards third countries. In 1975. The Lome Convention was signed between the European Communities and ACP-countries. On March 1979, European Monetary System (EMS) was launched as the major achievement of this period, which created a financial stability within the Community and represented the major step toward economic union. The EMS was built on the concept of stable, but adjustable exchange rates defined in relation to the newly created European Currency Unit (ECU) – a currency basket based on weighted average of EMS currencies. Within the EMS, currency fluctuations were controlled through Exchange Rate Mechanism and kept within ± 2,25 % of the central rates. The system included an intervention mechanism and preventive tool – once the exchange rate of currency reached 75 % of the maximum fluctuation margin authorised, the currency was considered as divergent and the country had to take remedial action through interest rates and fiscal policy adjustments. In the event of the maximum fluctuation margin being reached, central banks had to intervene by buying or selling currency to avoid the margin being exceeded. From institutional perspective the key development of the seventies was that, from 1974 on, consultation between the Member States at the level of Heads of State or Government became a regular exercise. As top-level political leaders had to be involved in forging compromises between Member States in order to improve the efficiency and decision-making in Europe, the so-called European Council, namely the meeting of Heads of State or Government, became the forum for taking the key decisions on strategic issues, compromises and guidelines. X. The Single European Act I. In 1984. Compromise was achieved in Fontainebleau. Expanding the financial resources, increasing the upper level of the VAT from 1 to 1, 4 %. Due to the oil crisis and periods of recession ‘non customs-related restrictions’ multiplied within the Community in order to protect national markets. Not only did these restrictions make it possible to realise a common market as set forth in the Treaty of Rome, they also represented a threat to the results already achieved. The elimination of these restrictions were fundamental task to create a pure internal, common market. During the lengthy period following the second oil crisis, it became increasingly apparent that the only recipe for boosting European competitiveness was deregulation. The elimination of various national-like administrative regulations would have been impossible if the system of unanimous voting had been maintained. Making the markets more flexible + creating a real common market became an urgent issue for the EC of the middle eighties. In 1985 the European Commission prepared a White Paper under the guidance of Lord Cockfield, which contained a plan for single market, to be implemented by 1992. The White Paper was aimed at removing all restrictions hindering the establishment of a real common market, such as obstacles of a physical nature (border formalities and controls), financial (budgetary and taxation rules) or technical nature (differing Member State legislation, standards and other national – typically technical – regulations). The Single European Act was signed on 18 February 1986 and entered into force on 1 January 1987. X. The Single European Act II. In fact, a single market programme meant a harmonisation of Member State legislation on the basis of about 300 Community directives between 1987 and 1992. The purpose of this intensive legislative programme was to remove any barriers that still hindered the free movements of goods, services, capital and labour, whether technical, physical, or financial. The programme of creating a single market included the elimination of various protectionist national regulations and standards, the removal of obstacles to the movement of capital, the harmonisation of public procurement rules and the liberalisation of a range of service sectors. The influence of European Parliament was also extended, the competence of the European Commission was widened. Significant changes were made in the voting system of the Council, increasing the importance of qualified majority voting. The Single European Act included the rules of the „European Political Cooperation” as well. The Single European Act eventually institutionalised the existing de facto cooperation. European Political Cooperation was directed towards the coordination of national foreign policies in order that Member States could develop a common standpoint on given matter, based on intergovernmental consultation, and in this way act together. The European Council was also institutionalised by the Single European Act in foreign policy issues. The European Council main task is to forge compromises between the Member States and is a forum for taking key decisions and strategic issues, compromises and guidelines. The task of adopting legislative acts and specific decisions remained with the ministerial Council. X. The Single European Act III. The Single European Act not only meant the introduction of an internal action plan but also qualitative changes in the external relationships as well(see: the Schengen Agreement and the establishment of the European Economic Area). Under the Agreement signed at Schengen in Luxembourg on 14 June 1985, the Benelux countries, France and the Federal Republic of Germany agreed that they would gradually remove their internal border controls and introduce freedom of movement for all individuals. The Agreement was supplemented by the Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement (Schengen Implementing Convention), which laid down the rules of implementing the Agreement. According to the provisions of the Convention, the Agreement and the Implementing Convention entered into force on 26 March 1995, with Spain and Portugal having joined the original five signatories. Because of the European Communities had decided on creating a single internal market, negotiations were started on how the EFTA countries with a similar level of development in terms of market economy could be included and a yet wider single European market established. Finally, the European Communities and six EFTA Member States decided to create a large European economic area through extending the single market to EFTA and started negotiations in June 1990. As a result, the twelve European Community member countries and the six EFTA members (Austria, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden) signed the Treaty of the establishment of the European Economic Area (EEA) on 2 May 1992, which became effective on 1 January 1994 with the participation of 17 states. The EFTA states took over approximately 80% of the rules regulating the single market so as to provide for the internal market conditions required for the common economic area (exceptions are agriculture and fisheries). Another important feature of participation in the EEA is that non- EU EEA members are consulted in the course of the elaboration of new Community legislation falling within its sphere of competence. XI. Reforms of the CAP and the common budget in the 80’s European Commission: in the field of agricultural policy it was essential eliminate the unlimited subsidies and harmonise the guaranteed prices to the world market prices. Guaranteed acquisition was limited by quotas. Main targets were the followings: supporting environmental friendly projects, production quotas, early retirement, retraining programmes, supporting young farmers. The European Communities should abandon with the formal system of export subsidies (higher internal than the world market prices, payment of differences as subsidies for the agricultural workers). Internal support was reduced by 20 % and export subsidies and tariffs were also cut within 6 years. Cereal prices were cut by 29 % and beef prices by 15 % within 3 years. After the three form of financial resources, the First Delors-Package introduced a fourth financial resource that was based on the Gross National Income (GNI) of the Member States. The upper level of the GNI was 1, 2 % that should be achieved till 1992. The fourth financial resource was complementary solution. It was applied when the Member States couldn’t fulfill their financial requests from the common budget resources. XII. The project of the Economic and Monetary Union In April 1989 the Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union, chaired by the president of the Commission, Jacques Delors defined the monetary union objective as a complete liberalisation of capital movements, full integration of financial markets, irreversible convertibility of currencies, irrevocable fixing of exchange rates, and the possible replacement of national currencies with a single currency. The report indicated that this could be achieved in three stages, moving from closer economic and monetary coordination to a single currency with an independent European Central Bank and rules to govern the size and financing of national budget deficits. The three stages towards EMU were the followings: Stage 1 (1990-1994): Complete the internal market and remove restrictions on further financial integration. Establish the European Monetary Institute to strengthen central bank co-operation and prepare for the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). Stage 2 (1994-1999): Plan the transition to the euro. Define the future governance of the euro area (the Stability and Growth Pact). Achieve economic convergence between Member States. Stage 3 (1999 onwards): Fix final exchange rates and transition to the euro. Establish the ECB and ESCB with independent monetary policy-making. Implement binding budgetary rules in Member States. On July 1989. (Madrid) The European Council’s decision about the introduction of the Stage 1 of Monetary Union + recalling of intergovernmental conference for drawing up the Treaty of Monetary Union. XIII. The Maastricht Treaty I. The political atmosphere of the eighties, that replaced the eurosclerosis of the seventies, promoted the deepening of integration and provided an appropriate background for the further development of European integration toward an economic and political union. It was already decided at the time of the adoption of the Single European Act, that the Member States should investigate the feasibility of a transition to an economic and political union in the framework of an Intergovernmental Conference (IGC). Significant political changes happened in world politics (The communist block was dissolved, political changes in Central and Eastern Europe, the issue of German reunification). The Summit meeting of July 1990 decided on convening an Intergovernmental Conference for preparing a treaty on political union. The Maastricht Treaty, which was signed on 7 February 1992, brought fundamental changes to the integration process. The changes were the followings: - To deepen economic integration, the Member States decided to join in an Economic and Monetary Union. To promote closer political integration, they created a Common Foreign and Security Policy. Common aims were identified in the area of home affairs and justice. EU citizenship was introduced and the full freedom of people’s movement was also decided on. Introducing the name European Union (But EU isn’t a legal entity, rather it represents a political notion). Three-pillar structure was established (First pillar: three Communities that were already in operation, including the EMU; Second pillar: Common Foreign and Security Policy; Third pillar: Cooperation on Justice and Home Affairs: based on intergovernmental cooperation. - The competences of European Parliament was extended + application of qualified majority voting in the Council instead of unanimity decision-making. XII. The Maastricht Treaty II. The Maastricht Treaty introduced the name ‘European Union’ (EU). While this notion refers to deeper and more comprehensive cooperation compared to the earlier ‘European Communities’, it should be noted that the European Union didn’t replace the three communities earlier. One the one hand, it didn’t terminate them and, on the other hand, the EU doesn’t have an independent legal status, which has remained a privilege of the three Communities. Thus, the European Union is not a legal entity; rather it represents a political notion. As regards the Communities, the Maastricht Treaty changed the term ‘European Economic Community’ to ‘European Community’, thereby implying a general scope of competence of this Community with respect to the common market, compared the restricted competence of the other two Communities. Thanks to the Maastricht Treaty, a specific three-pillar structure was established. The first pillar was determined as the three Communities that were already in operation, i.e. the European Communities, including the tasks related to the new aims of the economic and monetary union. As they did not want to establish very close Community-type cooperation in the areas aimed at creating a political Union, there was a need to create two new cooperation arrangements of a looser type, i.e. to set up two new pillars. XII. The Maastricht Treaty III. The second pillar was the Common Foreign and Security Policy. CFSP, however, cannot be understood literally as a common foreign policy, since it doesn’t mean that the Member States have a single, joint, foreign policy. Neither can it be seen as Community policy, since it works entirely on an intergovernmental basis. The principles of CFSP call for an ongoing exchange of information on foreign policy and security issues between the Member States and for aligning national positions. These objectives are to be attained and put out into action through legal instruments of general guidelines, common strategies, common positions and joint actions. The third pillar was the Cooperation in the fields of Justice and Home Affairs (areas that belonged to this field were the followings: asylum policy, the control of external borders of Member States, immigration policy and questions relating to nationals of third non-member countries, fighting against drugs and international fraud, judicial cooperation in criminal matters, custom cooperation and police cooperation on preventing and combating terrorism, illicit drug trafficking and other serious forms of international crime). One of the purposes of the Maastricht Treaty was to finally settle disputes emerging in connection with coinciding scopes of Community and Member State competence. To this aim, the Treaty included the principle of subsidiarity in Community decision-making. According to this principle, an issue should be decided on at the Community level if the aim concerned cannot be realised at the national level and the measure proposed can probably be carried out with better success and efficiency at the Community level owing to its extent and effects. XIII. The Stage 2 of the Economic and Monetary Union and the Maastricht convergence criteria In Maastricht Member States decided the convergence criteria that was necessary to take part on Stage 3 of the Economic and Monetary Union. The convergence criteria were the followings: 1. The inflation rate cannot more than 1,5 percentage points above the rate of the three best performing Member States. 2. The government deficit cannot more than 3 percent of the GDP. 3. The government debt cannot more than 60 percent of the GDP. 4. The long-term interest rate cannot more than 2 percentage points above the rate of the three best performing Member States in terms if price stability. 5. Participation in ERM II for at least 2 years without severe tensions. The Monetary Union supposes to reduce the disparities among the Member States + increasing the financial resources for the development of regions lagging behind. On December 1992. In Edinburgh the European Council decided on the redistribution of financial resources for seven years period (including the candidate countries). XIV. The Amsterdam Treaty According to the articles of the Maastricht Treaty it was essential held another Intergovernmental Conference in 1996 to review and amend the Treaty. In 1996. Intergovernmental Conference was opened in Turin. Main targets: to assist a comprehensive reform of the operation of the Union + revision of the Maastricht Treaty. On 2 October 1997: Amsterdam Treaty was signed and entered into force following the required ratification by the Member States on 1 May 1997. The main elements of the Amsterdam Treaty were the followings: 1. Significant widening of the decision-making competence of the European Parliament (European Parliament received co-decision making procedure in many fields except financial and economic issues and had right to nominate the President of the European Commission). 2. Changes were made in the area of Common Foreign and Security Policy (High Representative for CFSP was nominated by governments that represented the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the EU). 3. Progress was made in intensifying cooperation on justice and home affairs (integration of the areas of external and internal border controls, immigration, asylum and judicial cooperation on civil matters into the first pillar). 4. Employment policy was set on Community level. Member States were required to coordinate the orientation and purposes of their respective national employment policies along guidelines adopted mutually each year. Criticism: postponing institutional reforms (extension of Council decisions requiring qualified majority voting; re-weighting of votes in the Council; determination of the composition and size of the Commission). XV. The introduction of euro The 1995 Madrid European Council agreed on the name for the new currency – the euro – and set out the scenario for the transition to the single currency that would start on 1 January 1999. The 1997 Amsterdam European Council agreed the rules and responsibilities of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) which aims to ensure fiscal discipline under EMU. The European Commission was given the key responsibility of monitoring adherence to the SGP. In May 1998, 11 Member States met the convergence criteria and thus formed the first wave of entrants which would go on to adopt the euro as their single currency. These were Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, and Finland. Denmark and the United Kingdom had ‘opted out’ from participating in the third stage of EMU, while Greece and Sweden did not fulfill all the criteria. The ECB and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) were established in June 1998, replacing the EMI, and on 1 January 1999 the third stage of EMU began. On 31 December 1998, the conversion rates between the euro and the currencies of the participating Member States were irrevocably fixed. On 1 January 1999, the euro was introduced and the Eurosystem, comprising the ECB and the national central banks of the euro-area Member States, took over responsibility for monetary policy in the new euro area. This was the beginning of a transitional period that was to last three years and end with the introduction of euro banknotes and coins, and the withdrawal of national banknotes and coins. On 1 January 2002. Introduction of euro banknotes and coins. National banknotes and coins were withdrawn. Main target: to harmonise the monetary and economics policy. XVI. The AGENDA 2000 The EU had to specify a financial framework for funding the enlargement process and accepting new Member States. The Heads of State or Government of the Member States made an effort at their Berlin summit on 25 March 1999 to handle the budget and reform package within the framework for the 2000-2006 period paying attention to the eastward enlargement. AGENDA 2000 determined the EU’s financial perspectives (budgetary framework) for the 2000-2006 period, in which provisions were made, from the year 2002, in the form of a budgetary item with concrete figures, to allow for the possible admission of new Member States. The main signficance of AGENDA 2000 - which bears the subtitle „For stronger and wider Europe” - was that the Commission dealt with the EU’s internal reforms, future strategy and enlargement in a single document. It even specified the financial conditions for the accession on new Member States, to the extent that the Commission’s financial perspectives for the 2000-2006 period included a separate budget line for expenses related to the new Member States. The „stronger and „wider” Union. i.e. deepening and widening, appeared as common pointed out the feasibility of eastward enlargement while preserving common and Community policies. Moreover, it attributed an overall positive impact to enlargement from the entire EU’s perspective. XVII. The crisis of European Commission and the Treaty of Nice During 1998 financial infringement was unveiled by the European Parliament in the departments and directories of the European Commission. Because of the infringements the European Parliament didn’t adopt the accounts of budget in 1996. Establishment an investigation committee (5 members). The result of investigation was to be found nepotism and irregularities. After the decision of the European Parliament the European Commission headed by Jacques Santer resigned completely. In 1999 Romano Prodi was nominated as President of the European Commission. The Cologne Summit held on 3 and 4 June 1999 decided to convene another Intergovernmental Conference in the first half of 2000 that would close by end of 2000. Main targets of the Intergovernmental Conference were the followings: to promote the institutional reform + process of decision-making. The Treaty of Nice was signed on 26 February 2001 and entered into force on 1 February 2003. XVII. The provisions of the Treaty of Nice The provisions of the Treaty of Nice were the followings: 1. The Treaty of Nice extended the role of majority voting in EU decision-making against unanimity-based decisions and modified Member State participation in decision-making so that population weights were better reflected in the decision-making bodies of the EU. 2. The Treaty extended decisions made through qualified majority voting to a number of areas such as industry policy, economic and social cohesion and economic and financial cooperation with third countries. The Treaty restricted the option to set a Member State veto, and further increased the influence of the European Parliament in passing decisions. 3. As regards Community institutions, the Treaty of Nice specified the weights to be assigned to each country in the 27-member Union (comprising the then 15 Member States and the 12 candidate countries still engaged in negotiations). 4. Furthermore the Treaty facilitated the use of enhanced cooperation between Member States, making it possible for countries intending to proceed with integration at a faster rate to deepen their integration in certain areas even if some other Member States decided not to. • Criticism: insufficient expansion of the scope of qualified majority decision-making and of the competence of the European Parliament (unanimity-based decisions were retained in relatively large number of cases) and the preservation of a decision-making system that still lacked transparency for the average citizen. • The undoubted importance of the Treaty of Nice was that its entry into force opened the way to the historical eastward enlargement . The Member States decided to convene another Intergovernmental Conference in 2004. (to profound institutional restructuring of the Union with the inclusion of the new members and candidate countries) XVIII. The European Convention After signing the Treaty of Nice by the Member States on 26 February 2001, discussion was renewed about the faster or slower rate of integration process. France attacked the federative conceptions and those endeavors that wanted to narrow the integration process only for economic field. The European Parliament emphasized the necessity of evaluating institutional reforms. The ratification process was stopped, because the Irish referendum refused the application of the Treaty of Nice. Laeken Summit was held on 14-15 December 2001. The Laeken Declaration emphasized the democratic strengthening Europe’s global participation and taking steps to better meet the needs of citizens (appropriate definition and division of competencies within the Union; simplification of the instruments of the Union; increased transparency, democracy, and efficiency; and a constitution for the citizens of Europe). The Heads of State or Government and Member States decided to set up a broad body called Convention (assisted not only by representatives of the national governments but also by representatives of national parliaments, as well as representatives of the institutions of the Union). The Convention was established on 28 February 2002. The Convention had to report to the European Council and submit proposals to the Intergovernmental Conference. The Convention prepared the draft of a new Treaty for the European Union. The draft Treaty was named the Constitutional Treaty, officially the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe. XIX. The Constitutional Treaty At the end of a period of almost 18 months, the Convention completed its work on 10 July 2003 by adopting the draft Constitutional Treaty. Intergovernmental Conference was called on by the European Council on 4 October 2003. The IGC set itself the new treaty framework to guarantee that EU could function smoothly with 25, 27 or possibly even more Member States and the same time make Union’s institutions and decision-making simpler, more democratic and more transparent for citizens. The Constitutional Treaty was adopted at the Brussels Summit on 17-18 June 2004. As a tribute to the Treaty of Rome of 1957, the 25 Member States signed the new Treaty on 29 October 2004 in Rome. The Constitutional Treaty main targets were the followings: - to improve the functioning of the European Union by simplification and guarantee more transparency and efficiency; - to merge the three pillars and to create a single legal framework and give the European Union legal personality; - to specify the areas where the Union would have competences, the scope of its competences, where it could take decisions, and where it could act; - to reduce the number of areas where unanimity was required for decisions and redesign the system of weighted votes (the introduction of double majority voting; requiring the support of at least 55 % of the Member States representing no less 65 % of the Union’s population). - to cut-back the number of Commissioners from 2014 (system of rotation). - to establish the permanent President of the European Council and the Union Minister for Foreign Affairs. XX. Internal crisis of the European Union The Constitutional Treaty was refused by France (54, 8 No votes) and Netherlands (61, 7% No votes) on referenda held on 29 May and 1 June 2005. Reasons behind the negative outcome of the French and Dutch referenda were the followings: -the electorate’s dissatisfaction with the work of the domestic political elite, poor economic prospects; increasing unemployment; social insecurity and the problems of immigration. In the first half of 2007. Germany assumed the Council Presidency. The German Presidency strived on reconciling the position of the few Member States mentioned that wished to amend the text with the position of the majority, who preferred maintaining the provisions of the Constitutional Treaty. The Berlin Declaration that was signed on 25 March 2007 had three implications for treaty reforms: 1. The Member States were ready to do all that was necessary to resolve the impasse by adopting a new Treaty; 2. they were prepared to ratify that Treaty by 2009; 3. the new Treaty would not have to be „constitutional”. Decision was taken about the new Treaty at the summit of 21-22 June 2007. The Member States decided to discard the adjective ‘constitutional’ and place the Union a new basis by means of a Reform Treaty amending the current Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community. The new Reform Treaty didn’t replace the EC Treaties, only amend them. It renamed the EC Treaty as the „Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union”, thereby conferring legal personality on the EU and abolishing the three pillars. The Member States agreed on a mandate for a new Intergovernmental conference convened on 23 July 2007 to finalise the Reform Treaty. XXII. The path to the Treaty of Lisbon Contrary to the Constitutional Treaty, The Reform Treaty doesn’t state explicitly the supremacy of Community law. The Reform Treaty doesn’t include references to the Union’s symbols – the flag, the anthem and the motto – either. The Reform Treaty doesn’t incorporate the Charter of Fundamental Rights into the Treaties, but it does include a reference to the rights enshrined in the Charter. The Union Minister for Foreign Affairs proposed by the Constitutional Treaty will be replaced by the name „High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy”. Another important changement was that the double majority voting will only be used from 1 November 2014 ( and not from 2009 as originally proposed) with an extra safeguard clause allowing the Member States to request the application of the current qualified majority voting system for individual decisions until 31 March 2017. On 13 December 2007. The Reform Treaty (Treaty of Lisbon) was signed by the Member States. On 12 June 2008. The Treaty of Lisbon was refused by a referendum, which was held in Ireland (53, 4 % No votes), but on 2 October 2009, 57 % of the population supported it. On 1 December 2009. The Treaty of Lisbon entered into force. XXIII. The content of the Treaty of Lisbon I. It’s important to emphasize that the Treaty of Lisbon doesn’t replace the Treaty on European Union (EU Treaty) and the Treaty establishing the European Community (EC Treaty); it only amends them and renames the latter the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union. The Treaty of Lisbon in an amending Treaty in classical sense: it amends but doesn’t replace the Treaties in force. Human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and the respect for human rights: these are the core values of the EU which are set out at the beginning of the Treaty of Lisbon. They are common to all Member States, and any European country wishing to become a member of the Union must respect them. Promoting these values, as well as peace and the well-being of the Union’s peoples are now the main objectives of the Union. These general objectives are supplemented by a list of more detailed ones, including the promotion of social justice and protection, and the fight against social exclusion and discrimination. The Treaty of Lisbon makes significant advances regarding the protection of fundamental rights. It opens the way for the Union to seek accession to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. The EU therefore acquires for itself a catalogue of civil, political, economic and social rights, which are legally binding not only on the Union and its institutions, but also on the Member States as regards the implementation of Union law. The Charter lists all the fundamental rights under six major headings: Dignity, Freedom, Equality, Solidarity, Citizenship and Justice. XXIII. The content of the Treaty of Lisbon II. The Treaty of Lisbon confirms three principles of democratic governance in Europe: - Democratic equality: the European institutions must give equal attention to all citizens - Representative democracy: a greater role for the European Parliament and greater involvement for national parliaments - Participatory democracy: new forms of interaction between citizens and the European institutions, like the citizens' initiative - The treaty also clarifies the relations between the European Union and its member countries. INSTITUTIONAL CHANGEMENTS: Parliament’s powers have been gradually extended in law-making (ordinary legislative procedure has been extended to several new fields such as legal immigration, penal judicial cooperation, crime prevention, police cooperation and some aspects of trade policy and agriculture). The new Treaty confirms the established practice of working with a multiannual financial frameworks, which Parliament must approve. It also abolishes the former distinction between ‘compulsory’ expenditure and ‘non-compulsory’ expenditure, with the result that Parliament and the Council determine all expenditure together. Under the Treaty of Lisbon, the European Parliament’s assent is required for all international agreements in fields governed by the ordinary legislative procedure. XXIII. The content of the Treaty of Lisbon III. The Treaty of Lisbon gives the national parliaments greater scope to participate alongside the European institutions in the work of the Union. The clause of the Treaty deals with their right to information, the way they monitor subsidiarity, mechanism for evaluating policy in the field of freedom, security and justice, procedures for reforming the treaties. The Treaty of Lisbon enforces the principle of subsidiarity. Any national parliament may flag a proposal for EU action which it believes doesn’t respect this principle. This can happen through a two-stage procedure: - if one third of national parliaments consider that the proposal is not in line with subsidiarity, the Commission will have to re-examine it and decide whether to maintain, adjust or withdraw it -if a majority of national parliaments agrees with the objection but the Commission decides to maintain its proposal anyway, the Commission will have to explain its reasons, and it will be up to the European Parliament and the Council to decide whether or not to continue the legislative procedure. Citizens’ initiative: whereby one million citizens, from any number of member countries, will be able to ask the Commission to present a proposal in any of the EU’s areas of responsibility. One of the new elements of The Treaty of Lisbon that it clarifies the scope of competences. The Treaty makes distinctions between exclusive powers (for example in fields like the customs union, the common trade policy and competition); supporting, coordinating or complementary action (for example in areas like culture, education and industry, the Union may only support action by the member states); shared powers (for example in other fields, like environment, transport and consumer protection, the Union and the member states share lawmaking power, not forgetting subsidiarity). XXIII. The content of the Treaty of Lisbon IV. According to the Treaty of Lisbon the European Council becomes a full EU institution. Although it doesn’t gain any new powers, it is headed by a newly created position of President. The President is elected by the European Council for 2½ years, the main job of the president is to prepare the Council’s work, ensure its continuity and work to secure consensus among member countries. The President cannot simultaneously hold any elected position or office nationally. The main changes in the decision-making process within the Council of the European Union: The qualified majority voting will be extended to many new policy areas (e. g. immigration and culture). In 2014, a new method will be introduced – double majority voting. To be passed by the Council, proposed EU laws will then require a majority not only of the EU’s member countries (55 %) but also of the EU population (65%). This will make EU lawmaking both more transparent and more effective. It will be accompanied by a new mechanism enabling a small number of governments (close blocking minority) to demonstrate their opposition to a decision. Where this mechanism is used, the Council will be required to do everything in its power to reach a satisfactory solution between the two parties, within a reasonable time period. European Commission The Treaty offers the perspective that a Commissioner from each Member State becomes Member of the Commission, while under the former Treaties that number would have to be reduced to a number inferior to that of Member States. Another major change, there is a direct link between the results of the European elections and the choice of candidate for president of the Commission. The President has the power to dismiss fellow Commissioners. XXIII. The content of the Treaty of Lisbon V. The creation of EU High Representative for Foreign and Security policy / Commission vice-president is a new element introduced by the Treaty of Lisbon. It should ensure the consistency in the EU dealings with foreign countries and international bodies. The High Representative has a dual role: representing the Council on common foreign and security policy matters and also being Commissioner for external relations. Conducting both Common Foreign Policy and Common Defence Policy, she chairs the periodic meetings of member countries’ foreign ministers (the „Foreign Affairs Council”). She represents the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy internationally, assisted by a new European external action service, composed of officials from the Council, Commission and national diplomatic services. The Treaty also introduces a single legal personality for the Union that enables the EU to conclude international agreements and join international organisations. The EU is therefore able to speak and take action as a single entity in the international politics. No significant changes have been made to the role or powers of the European Central Bank or the Court of Auditors. However, the Treaty broadens the scope of the European Court of Justice, especially as regards police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, and changes some of its procedures. Conclusion Forms of integration (from The Treaty of Rome to the Maastricht Treaty): Free trade area: trade between countries within the area is liberalised while each member country pursues its national trade policy with those outside the area (for example: EFTA) Customs union: trade between countries within the area is liberalised (the movement of goods and services in unrestricted) while common customs tariffs are imposed on those outside the area, and a common commercial policy is pursued (see the Treaty of Rome) Common market: more than a customs union in that (in addition to free movement of goods and services) the flow of production factors (capital and labour) is also liberalised, thereby creating the „four fundamental freedoms” (the free movement of goods, services, capital and workers). Single (internal) market: an advanced version of a common market where, in addition to customs and quantity limitations, obstacles of a „non-customs character” (of a non-commercial nature) – be they physical (border formalities, border controls), fiscal (budgetary or tax rules) or technical (resulting from the differences between the laws, standards or regulations of Member States) – hindering the free movement of goods, services, capital, and workers are all eliminated ( see the Single European Act). Economic union: in addition to a common market, integration of economic policies is also realised, which means that national economic policies are coordinated, harmonised and, as the final aim, unified at the community level; an important element of economic union is the use of the single currency and the monetary union thereby established (see the Maastricht Treaty). Political union: gradual transfer of governance and legislation to the community level; an important element of this process is the shaping of a common foreign policy and handling of home affairs and justice issues at the community level (see the Maastricht Treaty).