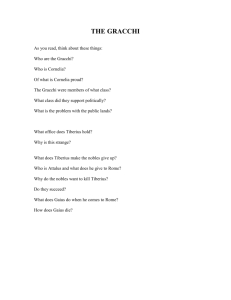

HIS 18 – Part 6

advertisement

CORNELIA, MOTHER OF THE GRACCHI 1. We noted before how CORNELIA came from the very heart of the Roman elite. i) Her father and paternal ancestors had been distinguished office holders for centuries. ii) The same was true of her maternal ancestors. 2. Cornelia’s married life ran, in so many ways, parallel with that of her mother, AEMILIA PAULLA, that (it was suggested) Cornelia must have been greatly influenced by her - especially since Aemilia appears to have been close to both her daughters. AEMILIA PAULLA (Cornelia’s mother) [we saw] was, reputedly, 1. a) mild-mannered, but b) fiercely loyal to her husband who came under a lot of criticism from his peers for his adoption of the new liberal “Greek” lifestyle which began to influence Roman society and challenge many of its traditional values in the decades immediately after 200 BC. 2. She also appears to have enjoyed an unusual freedom for a woman of her status – both in the disposition of her wealth and in her interactions with others in society – even though she will have been in the manus of her husband. 3. AND, like her younger daughter, she was a widow for a long time before her death [which occurred when she was about 67 years old], never having re-married. CORNELIA 1. Born about 190 BC, she married in 172 BC at 18 – quite late for a daughter from a leading senatorial family – and died before 100 BC [when she was at least in her late 80s]. 2. i) Her husband, TIBERIUS SEMPRONIUS GRACCHUS, was a middle-aged senator of distinction who held the consulship twice (in 177 and 163 BC) and the censorship in 169 BC. ii) He was born about 217 BC, married at the age of about 45 (and so was about 27 years older than Cornelia) and died suddenly in 154 BC at the age of about 63, after 18 years of marriage. 3. CORNELIA and TIBERIUS had 12 children, but only three survived beyond childhood - Sempronia (born 170 BC), Tiberius (born about 165 BC), and Gaius (born 154 BC). 4. CORNELIA was to have four grandchildren - but only one reached adulthood: her daughter had no children, her son Tiberius had three sons who all died very young, and her son Gaius had a daughter [whose daughter Fulvia, in her turn, married three leading Roman statesmen, the third, Marcus Antonius, putting her head on a coin – the first living Roman woman to appear in this way]. 5. a) CORNELIA herself was widowed in her late 30s but never remarried [despite offers and despite the ‘normal’ expectation in Roman society]. b) As a widow she was to become an icon – the devoted mother who gave herself exclusively to her three children (especially to her two sons) when she was left to raise them alone when they were, respectively, 15, about 10, and a babe in arms. c) She was, allegedly, one of the very few mothers who alone influenced her sons’ political careers, but how far the stories told about her were true is a matter of great debate – at best they were probably greatly enhanced in the re-telling. CORNELIA AS THE IDEAL MOTHER 1. a) Cornelia was so highly regarded that, eventually, the Roman state erected a statue in her honour – an unusual development for the “Republican” period. b) Unfortunately the statue itself has not survived but its base has. 2. If the story is to be believed, in her lifetime her fame was enough for her to have been approached with marriage in mind even by a king, Ptolemy [probably Ptolemy VIII] of Egypt, but she refused his hand. [A subject which appealed to Laurent de la Hyre in the 1600s as a theme for a picture] 3. While the term seems not to have been used until quite late in the Roman period, CORNELIA is likely to have been admired even more for being a univira (“a woman who only ever had one husband”). 4. All her efforts after she became a widow [as already noted] were invested in the raising and education of her children – especially that of her two sons, normally the duty, by example, of boys’ fathers. STATUE BASE “CORNELIA DAUGHTER OF AFRICANUS [MOTHER] OF THE GRACCHI” “CORNELIA AFRICANI F GRACCHORUM” LAURENT DE LA HYRE (1606-1656) “CORNELIA REJECTS THE CROWN OF THE PTOLEMIES” 5. With her sons’ education in mind she brought to Rome [and clearly had the means to do so] Greek scholars to act as tutors to her boys - in particular Blossius (of Cumae [in Campania]) and Diophanes (of Mytilene [the capital of the island of Lesbos]) - and it seems likely that, as an advocate of ‘the new education’, she will have engaged in discussions with them herself alongside her own study of literature - all unheard of at this time in a Roman matrona, however distinguished. 6. One story of the place her children played in her life has been the subject of artists over the ages: i) when a wealthy visitor called on her one day and made a great display of the jewellery that she had brought with her and then asked Cornelia to show her her jewels, ……. ii) Cornelia produced her children and said that they were the only jewels she needed. Among the artists who chose to depict Cornelia are i) Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807), ii) Benjamin West (1738-1820), iii) Noël Hallé (1711-1781), iv) Joseph-Benoît Suvée (1743-1807), v) Jean-François-Pierre Peyron (1744-1814), vi) Tancredi Scarparelli (1866-1937), vii) an anonymous creator of a silk and paint scene (ca 1810), and viii) John Leech (with his “Comic History of Rome”). And there is the most famous sculptor of Cornelia and her two sons Jules Cavelier (1814-1894). ANGELICA KAUFFMANN (1741-1807) “Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, Pointing to her Children as Her Treasures” ca 1785 BENJAMIN WEST (1738-1820) NOËL HALLÉ (1711-1781) 1799 JOSEPH-BENOÎT SUVÉE (1743-1807) JEAN-FRANÇOISPIERRE PEYRON (1744-1814) 1779 TANCREDI SCARPELLI (1866-1937) “CORNELIA SHOWS OFF HER SONS” ANONYMOUS ‘SILK & PAINT ON SILK’ ca 1810 JOHN LEECH “COMIC HISTORY OF ROME” JULES CAVELIER (1814-1894) 7. Even when her sons were adults, had begun their political careers and, as “tribunes of the plebs” (Tiberius in 133 BC and Gaius in 122 and 121 BC), were challenging and upsetting the conservative establishment by advocating and trying to introduce reform [leading to the assassination of both], CORNELIA, allegedly, stood by them. 8. a) BUT Cornelius Nepos (Rome’s first biographer, writing about 50 years after Cornelia’s death) preserves a letter reputedly written by Cornelia to her son Gaius berating him [rather like the legendary Veturia] and demanding that, out of respect for her, he should restrain his political activity. b) The letter’s authenticity is very much in question, but, if genuine, it had little effect on him, since he continued with his programme of reform – with disastrous results. c) But, if genuine, the letter would be a rare example of a woman, however distinguished her family background, trying to influence the outcome of a public policy which she felt was contrary to the state’s best interests. d) If the letter is a ‘forgery’, the aim of reproducing it would have been twofold: i) to dissociate Cornelia from the disastrous political programmes of her sons; and ii) to reinforce to later generations her role as an ideal and heroic mother. 9. Cornelia retired to a villa near Misenum (near Naples) before the death of her younger son Gaius (in 121 BC) and continued to study literature and philosophy until her death before 100 BC in her late 80s, remaining a model for others to follow. Given the idealization of Cornelia after her death, she has to remain a somewhat elusive figure historically. AFTER CORNELIA 1. After Cornelia, no individual woman stands out in her own right for quite some time. 2. Certainly none is known well enough to merit close attention - although we might consider the marriages of some of the leading male political figures of the “Late Republic” since they can sometimes show us how marriages were a) initiated, and b) maintained, and c) ended for largely political reasons - again always amongst the members of the elite political classes. Lucius Cornelius Sulla (ca 138 – 78 BC) 1. Sulla (who came from a “patrician” family which had fallen on hard times financially) rose to one of the consulships for 88 BC largely because of his service to the state when he fought in the “Social War” between Rome and about half of its Italian allies (late 91 to 90 BC). 2. As consul he was assigned the task of bringing King Mithridates of Pontus (below the Black Sea) to heel because of his threats to Roman interests in Asia Minor, only to find his command transferred by “populist” political leaders to Gaius Marius. 3. Rather than accepting this reversal to his career prospects, Sulla marched on Rome with troops twice (once before going off to fight Mithridates and then after his success against him), revived the office of dictator after his second ‘march on the city’, and, as such, put in place a very conservative, anti-populist régime from 83 BC (accompanied by the bloodbath made legitimate by the posting of his “proscription lists” against all who opposed him). 4. He retired from a public role in politics in 79 BC and died in 78. LUCIUS CORNELIUS SULLA SULLA’S HEAD [right hand side] ON A MUCH LATER COIN He married five times and his marriages may have been arranged with his political advancement in mind (although, in his case, this is not always possible to show). a) i) At the age of about 28 in 110 BC he married a “Julia” [reported by the biographer Plutarch as “Ilia”], the marriage lasting six years (until 104 BC). ii) If this wife was a Julia, then she was “patrician” too and perhaps a cousin ‘once-removed’ of Julius Caesar. A marriage with someone from another “patrician” family which was not in the shadows like his branch of the Cornelii would probably have served Sulla well at an early stage in his career – given his families lean circumstances. iii) Together they had a son who died young and a daughter, Cornelia, whose daughter, Pompeia, in her turn eventually became Julius Caesar’s second wife [as we’ll see]. b) Sulla’s second wife was an Aelia – from a “plebeian” family. Virtually nothing is known about her, but she is likely to have belonged to the “nobility”. c) His third wife was a Cloelia, from another “patrician” family; Sulla divorced her after a fairly short time on the grounds that she was barren – and it was important to a member of the elite to have a son to carry on the family’s name and traditions – without having to resort to adoption (the quite common alternative way to obtain an adult son). d) i) His fourth wife was Caecilia Metella (Dalmatica) with whom Sulla had a son and a daughter, Cornelia; her second husband, Titus Annius Milo, was the political enemy of Publius Clodius whose sister Clodia was, allegedly, “notorious” [as we’ll see later]. CAECILIA METELLA (Sulla’s fourth wife) 1. Unfortunately we cannot say much about Caecilia Metella herself, but she was a member of one of the most distinguished “plebeian” families within the limited Roman ‘Republican’ “nobility”. 2. The Caecilii Metelli (perhaps the most outstanding branch of the Caecilii) had held consulships since at least the 280s BC – for two hundred years before our Caecilia’s birth. 3. Her father, Lucius Caecilius Metellus Dalmaticus (born about 160 BC), had gained an excellent reputation both as a political and as a military leader, had held one of the two consulships in 119 BC and one of the two censorships in 115 BC, serving as Pontifex Maximus (“head of the state religion”) from 115 BC. 4. For Sulla to marry her (eventually) would have reinforced his membership of the most intimate political circle in the state, but he was not her first husband. 5. She had been married earlier to an aging politician at the height of his career, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, from a distinguished “patrician” family, who was ‘leader of the Senate’ (princeps senatus). 6. And, with Scaurus, she had had two children – her daughter (again eventually) going on to be the second wife of Pompey the Great [Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus]. 7. When Caecilia Metella’s husband, Sulla, was in Asia Minor fighting King Mithridates and the political situation in Rome had erupted into conflict, she was forced to flee not only from Rome but from Italy. Roman wives did not go on postings with their husbands. 8. She joined Sulla in Greece and there gave birth to twins, a son and a daughter (the one who eventually married Titus Annius Milo [see above]). 9. We simply cannot say whether she had any influence on her husband’s public life – other than to help boost his auctoritas (‘social standing’) because of her own family background. Sulla again i) Sulla’s fifth wife, Valeria Messalla, had been married to Sulla for only two years when he died, his final child, another Cornelia, being born after his death. ii) The Valerii traced their origins to the earliest days of the Roman state, the branch to which Valeria Messalla belonged, becoming particularly distinguished (through their male representatives, of course) in the 260s BC at the time of the first war against Carthage (264-241 BC). But the Valerii Messallae were ‘in the doldrums’ between 154 and 61 BC [in terms of holding the highest offices in the state]. iii) In light of this, it is not clear how ‘useful’ Sulla’s marriage to her will have been politically – but he retired from politics at about the time of their marriage in any case and died within about two years. iv) His marriage to her will have been when he was about 58; her age at the time is not clear but it is said that she caught Sulla’s eye at the theatre. Her brother in 80 BC will have been about 24 and so Valeria Messalla is likely to have been of approximately the same age (so there was perhaps about a thirty year difference between them).