Introduction - Academic Integrity Office

advertisement

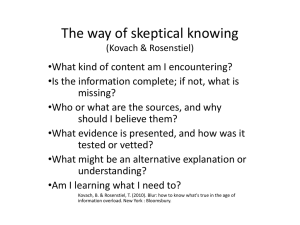

Memo To: Faculty and Instructors From: Margaret L. Usdansky, Director, Academic Integrity Office Date: September 8, 2014 Re: Ideas & Material for Engaging Students in Discussion of Academic Integrity This summer, the Academic Integrity Office (AIO) revamped its fall orientation programming with the goal of reaching more students more effectively. Rather than making as many individual presentations in as many classrooms as we can get to, we have focused on making presentations to groups of faculty and instructors and providing them with tools for use in engaging students in classroom discussion of academic integrity. The reason for our new approach is twofold: First, my experience at AIO and research on effective teaching underscore the need for students to hear directly from faculty and instructors on this topic. Students are most likely to hear and absorb messages about academic integrity when those messages come from the instructors who design, teach and grade their courses. Second, we are a staff of two. We can reach many more students by providing instructors with tools and information than by leading classroom discussions ourselves. To this end, I am providing faculty and instructors with a set of material aimed at engaging students in discussion of academic integrity. The attached material includes a list of recommended topics for discussion and related information and/or material to assist you in addressing each topic. The goal is to provide a menu of topics and material from which you may choose what you find most interesting and most relevant to the courses you teach. I invite you to modify these topics and materials to make them as relevant as possible to your courses – and to credit AIO and include citations we’ve provided when presenting enclosed material to students, whether in written or oral form. Many students note and puzzle over instructors who emphasize the importance of citation in written assignments but do not consistently include citations in their own class presentations. Finally, I encourage you to raise academic integrity in small, frequent “doses” over the course of the semester rather than designating one class session for discussion of this topic. Doing so will better convey to students the importance you place on academic integrity and will increase the odds that short classroom discussions and occasional reminders will catch students when they are most likely to listen attentively, that is, shortly before an assignment is due or an exam is scheduled. Please do not hesitate to contact AIO with comments, questions or requests for additional information by emailing or calling us at aio@syr.edu or 443-5412. 2 Topics for Engaging Students in Discussion of Academic Integrity Expectations 1. Why you value academic integrity in your classroom: The value of academic integrity may seem obvious to you, but students are often puzzled by acacemic integrity standards, particularly with regard to use of sources and collaboration. Students are accustomed to the exchange of unattributed ideas and information on websites and in social media. They know that politicians and corporate leaders often deliver speeches written by unnamed assistents. They may realize that unspecified editors substantially revise the words of journalists. And many students notice that some faculty take tremendous care with citation in written work but fail to cite sources for oral and visual work, for example, in classroom Power Point presentations. Expectations vary by context when it comes to collaboration, as well. Some instructors encourage students to study exams from past semesters and require group projects, group writing and group laboratory work. Other instructors forbid these practices. Students need to hear directly from you. Why do you value academic integrity in your classroom? How do you define academic integrity in your classroom? Where do you draw the line between allowed and prohibited collaboration on group work or joint studying? a. The central role of citation in research: Ask students what they know about your job. Most students know little about the work faculty and instructors do beyond teaching. Telling students about your area of expertise, the role that research plays in your career, and how citing and being citing by other academics affects you will help explain the value placed on citation in academia – and the expectation that students will cite sources they use even though only a minority of students expect to enter academia themselves. b. How research works: Students often imagine academic research as a one-shot deal, a quick event that confirms a hypothesis or answers a question immediately – forever. Walking students through an exercise designed to illustrate the evolution of an important research question in your field (particularly including the construction and destruction of consensus around answers to that research question) can help students appreciate the value of tracing the intellectual contributions of multiple researchers over long periods of time in understanding the evolution of knowledge. Another good exercise involves assigning students to read a peer-reviewed journal article in your field. Ask students to analyze the structure of the article: How many sections are there? What is the purpose of each section? Which sections contain more or fewer citations. What explains this variation? Additional useful talking points: Compare failure to cite sources to physical theft or to omitting a relative from a family tree. Students will laugh if you ask how many of them stole a cell phone last summer or left grandma off the family tree, but they’ll get the point. c. Making the case for academic integrity personal: Talk with students about tough ethical decisions you’ve made in the course of your academic career. What gray areas exist. How have you handled them? What have observed with regard to the academic integrity of other academics in your field, those you admire and those you do not admire? How do you feel when you believe one of your students has cheated? How might “small-scale” cheating in the classroom affect students later in life? Academic Integrity Office (AIO), Syracuse University, August 2014 3 Topics for Engaging Students in Discussion of Academic Integrity Expectations 2. What are the university-wide academic integrity (AI) expectations at SU, and what additional expectations apply in your classroom? Our website, academicintegrity.syr.edu, features a variety of information about SU’s university-wide expectations. The one-page “Summary of SU’s AI Expectations,” reiterates information provided to SU students twice an academic year in MySlice during pre-term check-in at the beginning of the fall and spring semesters. (At these times, students must update emergency contact information and provide an electronic signature agreeing that they will abide by the University’s AI expectations. Until they sign, students are unable to navigate to student information pages, including pages they need to view grades and change their course schedule.) The more detailed “Full Statement of SU’s AI Expectations” reproduces the entire discussion of academic integrity expectations contained in SU’s Academic Integrity Policies and Procedures. a. Understanding SU’s AI expectations: Depending on the nature and level of your course, you may wish to give students a copy of the “Summary of SU’s AI Expectations” and invite students to comment and ask questions. Caution students against assuming that they know everything they need to know about these expectations. Remind them that the bar for citation is higher in academia than in many other fields. Do they realize that they must receive written permission from both instructors before submitting the same written work in two courses? Do they understand the presumptive penalty for a first violation of academic integrity and how it varies by undergraduate or graduate status? b. Understanding course-specific expectations: Regardless of the subject and level of your course, you should discuss what forms of collaboration will be allowed and what forms of collaboration will be prohibited in your course. If you consider the sharing of homework assignments or exams from current or past semester to violate academic integrity, you should make this clear to students. Similarly, you should draw clear distinctions for student if you allow collaboration in the initial phases of a project or laboratory assignment, but expect the final or written work to be performed independently. c. Using case studies to engage students in discussion of gray areas within AI standards: Included in this package of materials is a page (“Academic Integrity Case Studies”) of three case studies designed to help students to consider varied aspects of academic integrity. Feel free to use these case studies in your classes and to modify them to reflect realistic questions students might have about permissible and prohibited behavior in your courses with regard to citation and collaboration. If you develop additional case studies you are willing to share with other faculty, email them to aio@syr.edu. We’ll put them on our website and cite you as our source. Note: Some students prefer to think of academic integrity as straightforward and want you, the instructor, to tell them what to do and what not to do. It may be helpful to have students read the recent Chronicle of Higher Education article “Confuse Students to Help Them Learn” (8/14/2014 by Steve Kolowich, http://chronicle.com/article/Confuse-Studentsto-Help-Them/148385/). Academic Integrity Office (AIO), Syracuse University, August 2014 4 Topics for Engaging Students in Discussion of Academic Integrity Expectations 3. Giving students opportunities to hone their citation skills: Many, if not most, students need help in understanding standard citation practices when summarizing, paraphrasing and quoting other peoples’ ideas and words. Included in this package is a set of exercises (see “Tools for Teaching Use of Sources”) for helping student develop these skills. Our exercises draw from two websites featured on our own website: The Harvard Guide to Use of Sources and the Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL). Both provide wonderful, specific information defining what it means to summarize, paraphrase and quote from a source as well as relevant citation standards in each case. a. If writing and citation feature prominently in your course, you may want to consider developing a longer assignment to help students practice their citation skills. One option is to have students practice with an initial writing assignment involving readings related to your course and subject matter. Another option involves asking students to write about academic integrity itself or plagiarism cases specifically. Links to some recent articles on these topics can be found on our website, academicintegrity.syr.edu, including coverage of alleged plagiarism cases involving the website Buzzfeed, Montana Senator John Walsh, UNLV literature professor Mustapha Marrouchi, and members of the Notre Dame football team. You may also be interested in a writing assignment developed by English instructor Jeff Karon (“A Positive Solution for Plagiarism,” Chronicle of Higher Education, September 18, 2012), who directs his students to download, read and critique a paper produced by a paper mill. 4. Why do students (and others) cheat? Is college cheating on the rise? A number of resources are available if you would like to engage students in discussion of research on the prevalence of cheating in college and factors that discourage – or encourage – cheating in college and elsewhere. These include: a. Duke University professor of psychology and behavioral economics Dan Ariely, author of The (Honest) Truth about Dishonesty (Harper Collins, 2012), maintains a web page (http://danariely.com/tag/the-honest-truth-about-dishonesty/) describing his research, including tests of the efficacy of reminders and pledges on exams and essays (e.g. “I pledge that this work is solely my own….”) and his response to the illegal downloading of his book. A review of Ariely’s book by Joome Suh (Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, volume 52, issue 1, January 2013, pp. 106-107) is available through the SU library website via Web of Science. Academic Integrity Office (AIO), Syracuse University, August 2014 5 Topics for Engaging Students in Discussion of Academic Integrity Expectations b. Assumptino College English professor James Lang (Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty, Harvard University Press, 2013) focuses on four contextual factors that, in his reading of the cognitive psychology literature, encourage classroom cheating and what faculty can do to create contexts discourage cheating. The four factors Lang identifies are an emphasis on performance versus mastery of knowledge, high-stakes testing and evaluation, extrinsic versus intrinsic student motivation, and low expectations of success among students (Cheating Lessons, chapter 2, pp. 18-35). Lang summarized his arguments in an August 4, 2013 Boston Globe article provocatively titled “How College Classes Encourage Cheating” available at http://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/08/03/howcollege-classes-encourage-cheating/3Q34x5ysYcplWNA3yO2eLK/story.html. Ursinis College Politics Professor Jonathan Marks’ criticism of Lang for, in Marks’ view, failing to adequately address questions of character in cheating appeared in the Inside Higher Education in October 2013. This article, like Lang’s Globe piece, could spur good classroom discussion. Marks’ criticism is available online at http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2013/10/25/fight-against-cheating-character-countsessay#ixzz2jKDmt4xe. c. Rutgers Management professor Donald McCabe, the grandfather of research on the prevalence of college cheating, summarizes his research with collaborators Linda Kleve Trevino and Kenneth D. Butterfield in “Cheating in Academic Institutions: A Decade of Research” (Ethics & Behavior, 2001, volume 11, issue 3, pp. 219-232), which you can download from the SU library website via Web of Science. d. Data and trends in reports of academic integrity violations here at SU are available on our website at http://academicintegrity.syr.edu/annual-reports/. The 2013-14 report will be available soon. We are finalizing the data so as to include summer 2014 cases. 5. If you have ideas, comments, or additional material about academic integrity that you would like to let us know about, please email it to aio@syr.edu. We will be posting additional articles on our website over the course of the academic year. Academic Integrity Office (AIO), Syracuse University, August 2014 6 For Discussion: Case Studies in Academic Integrity Case 1: Johannes is taking a course in 20th century Latin American history. The class is conducted in Spanish. Johannes has fallen behind in the class and hasn’t begun a 10-page essay due the next morning. Stressed about the essay, Johannes stays up until 3 a.m. to finish a draft and emails it to his mother, asking her to point out any grammar errors and suggest revisions to strengthen his arguments. When Johannes wakes up at 9 a.m., he finds a reply email from his mom, incorporates her suggestions, and turns the paper in on time at 11 a.m. Is Johannes’ behavior academically dishonest? Does it violate SU’s AI policy? Would similar behavior be permissible in your course? Why or why not? What if all writing assignments for the class must be in Spanish, and Johannes’ mother is a native Spanish speaker? Does this change anything? Why or why not? What if Johannes’ mother has included a passage from a Spanish-language encyclopedia in the revisions she sent to him without citation? Does this change anything? Why or why not? Case 2: Emily is taking an upper-level political science class. Her professor asks students in the class to write a critique summarizing their own views on the strengths and weaknesses of arguments made by the author of a controversial new book on mass incarceration. Not knowing much about the subject, Emily decides to gather ideas for her critique by going online. She finds and reads three reviews of the book. Emily agrees with the views expressed by two of the reviewers and incorporates their opinions into her critique. Because she is drawing on the reviewers’ opinions – not facts – and because she agrees with those opinions, Emily does not cite the two reviews. Is Emily’s behavior academically dishonest? Does it violate SU’s AI policy? Would similar behavior be permissible in your course? Why or why not? What if Emily disagrees strongly with one critique she reads and makes the opposite argument in her own critique? Does anything change? Should Emily cite the critique she disagreed with? Case 3: Four students who live in the same learning community take a large chemistry class. The class breaks into small groups for labs, some of which are held on Mondays, others on Wednesdays. Ashley, whose lab meets on Monday, lends Sam a copy of her lab report so that he will be prepared for his lab on Wednesday. Has Sam been academically dishonest? Has Ashley? Would similar behavior be permissible in your course? Why or why not? The Academic Integrity Office (AIO), Syracuse University, August 2014 7 Tools for Teaching Use of Sources Introduction The Harvard Guide to Using Sources and the Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL) are both excellent resources for teaching use of sources to students. The short exercises below ask students to demonstrate summarizing, paraphrasing, and using direct quotations. You can provide your students with a short (1-2 page) academic text from any discipline to use for these exercises. The exercises may be modified to conform to the text you provide. You may find additional information on these topics on the Harvard Guide’s Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting webpage. Exercises Summarizing A summary is a succinct overview of the most important parts of a source. Summaries should be brief and contain necessary details only. Summarizes must always include citation. Directions: First, read the Harvard Guide’s section on summarizing. Next, read the text provided by your instructor and write a brief summary. Ask yourself the following questions: 1. Who is my audience, and how much prior knowledge should I assume they have about this source or subject? 2. What are the most important points in the text; what are the main points from the text that I want to convey? 3. Have I correctly cited the source using my instructor’s preferred citation style? Paraphrasing Paraphrasing involves restating another person’s information and ideas in your own words. Your wording must differ substantially from that of your source. Changing a word or even a few words is not sufficient. Paraphrased material must always include citation. Directions: First, read the Harvard Guide’s section on paraphrasing. Next, read the text provided by your instructor and paraphrase it. Ask yourself the following questions: 1. Have I completely and accurately restated all of the information presented in the original text? 2. Have I used only my own words? 3. Have I correctly cited the source using my instructor’s preferred citation style? The Academic Integrity Office (AIO), Syracuse University, August 2014 8 Quoting When you use a direct quotation, you are using the exact words from a source within your own writing. Quotations should be used sparingly, and only when it is essential for your readers to see the original words of the author. Quotations must always include citation. Directions: First, read the Harvard Guide’s section on quotation. Next, read the text provided by your instructor and select a sentence or two that you think is essential. Ask yourself the following questions: 1. Does this quotation convey something that I am unable to convey by paraphrasing or summarizing? 2. Did I use proper punctuation to indicate that I have quoted directly from a source? 3. Have I correctly cited the source using my instructor’s preferred citation style? Works Cited Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Harvard College Writing Program. Harvard College, 2014. Web. 30 July 2014. The Purdue OWL Family of Sites. The Writing Lab and OWL at Purdue and Purdue U, 2014. Web. 30 July 2014. The Academic Integrity Office (AIO), Syracuse University, August 2014