Edisto Revisited: A Novel

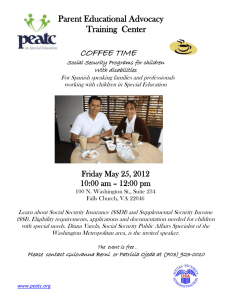

advertisement