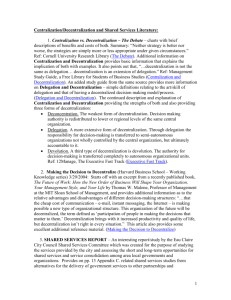

(Ayee and Amponsah, 2002). - University of Education, Winneba

advertisement