Alex Calder Presentation PowerPoint

advertisement

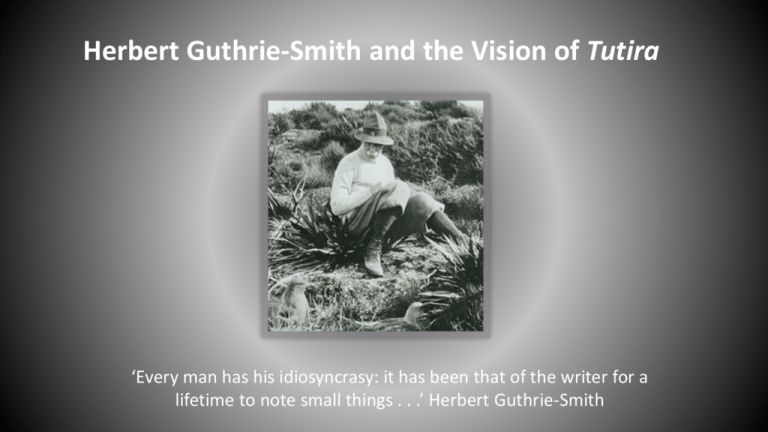

Herbert Guthrie-Smith and the Vision of Tutira ‘Every man has his idiosyncrasy: it has been that of the writer for a lifetime to note small things . . .’ Herbert Guthrie-Smith Pioneers! O, Pioneers! Oh, pioneers . . . When I am very earnestly digging I lift my head sometimes, and look at the mountains, And muse upon them, muscles relaxing. I think how freely the wild grasses flower there, How grandly the storm-shaped trees are massed in their gorges, And the rain-worn rocks strewn in magnificent heaps . . . . It is only a little while since this hillside Lay untrammelled likewise, Unceasingly swept by transmarine winds. In a very little while, it may be, When our impulsive limbs and our superior skulls Have to the soil restored several ounces of fertilizer, The Mother of all will take charge again And soon wipe away with her elements Our small fond human enclosures. If our mountains of Tongariro are included in the blocks passed through the court in the ordinary way, what will become of them? They will be cut up and sold, a piece going to one Pakeha and a piece to another. They will become of no account, for the tapu will be gone. Tongariro is my ancestor, my tupuna, it is my head; my mana centres around Tongariro. Te Heuheu Tukino, 1885. Herbert Guthrie-Smith 1861 - 1940 ‘... a record of minute alterations noted on one patch of land.’ To my backwoodsman’s heart, there is . . . something austere, distinguished even, in the brotherhood of weeds. They are the MacGregors of our artificial highlands seizing as of right—these hard faced children of the wilderness—conditions they must yet despise—leaf-mould, sieved peats, sharp sands, and shredded sods . . . . Centuries of condemnation and oppression have made them what they are . . . . Theirs has been that sad sharpening of perception that comes to dwellers beyond the pale, to creatures proscribed, to whom discovery is death. Who can doubt but that in the process of natural selection and the survival of the fittest, . . . that garden cress however circumspectly gripped has added a new fury to its seed ejaculation, that petty spurge beneath its decapitated head has developed a more sure and certain stem reduplication, that mouse-ear carast has evolved a more profoundly furtive concealment in the heart of his host? Such are the lowly ways whereby humble folk may face adversity and perpetuate themselves. One last word: he hopes that his readers have played the game, that they have not indulged the practice of skipping. If this has not been done, if every chapter has been read, they can rest assured that in examination, as it were under the microscope, of one sheep station, they have discovered what there is to be found in all . . . . Every station in Hawkes Bay has been moulded by a great rainfall; possesses legends and relics of a splendid aboriginal race; has been clothed with forest, flax, and fern; has been subdued by pioneers in desperate straits for cash and its equilibrium; has had its surface mapped by stock, its rivers affected by scour, and, lastly, has been or is in the process of being subdivided into smaller holdings. Right & above: Tutira c. 1939 ... a brief wrinkling of the epidermis of the earth, as evanescent as the shrug and stamp of a fly-pestered ox... The tenure of these runs was leasehold, and native leasehold at that; without exception the titles were flawed; the land was devoid of grass, the climate was wet, the access bad, the soil ungrateful and poor. There was no compensation for improvements. It seems impossible now that any reasonable soul could have believed there was either money or reputation to be made out of them. The truth is that [we] were not reasonable, that [we] did not think at all. … To this day I am unsure whether we were splendid young Britons, empire builders and so forth, or asses of the purest water. In those times, to think of an improvement was to be in love. . . . A thousand anticipations of happiness rushed upon the mind – the emerald sward that was to paint the alluvial flats, … the spurs over which the fencing was to run, its shining wire, its mighty strainers; … the glory of the grass that was to be.... Oh, those were happy days, … when every thought was for the run, when every penny that could be scraped together was to be spent on the adornment of that heavenly mistress. All sheep suffer from nostalgia, but the merino is perhaps the most miserably homesick beast on earth. Liberated in strange country, a mob of merinos will lie against the barrier—cliff, river, fence, whatever it may be—blocking their homeward route. Night after night, day after day, week after week, there they will camp, resigned to starvation. They will hug the fence-line that debars them from returning to their old haunts till their droppings are inches deep, until their lank frames reveal every bone. Soil erosion on ranges east of Lake Tutira, c.1939 The fenced-off section of bush is the Hanger, circa 1939. When a block of land passes, as it may do through the hands of ten holders in half a century, how can long views be taken of its rights? Who under these conditions can give his acres their due? Aue, taukari e, ano te kuware o te Pakeha kahoro nei i whakaaro ki to mauri o te whenua. Alas! Alas! That the Pakeha should so neglect the rights of the land, so forget the traditions of the Maori race, a people who recognised in it something more than the ability to grow meat and wool. ‘If this volume has a value, it is because of [its] insistence on the cumulative effects of trivialities’.

![Pioneers! O Pioneers! [excerpt] (1865)](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009625303_1-97477e83c178760551e424da5296a509-300x300.png)