Class 12 - Physics at Oregon State University

advertisement

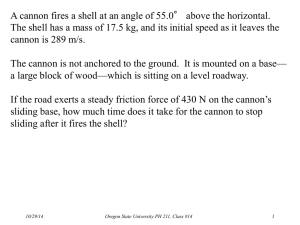

A cannon fires a shell at an angle of 55.0° above the horizontal. The shell has a mass of 17.5 kg, and its initial speed as it leaves the cannon is 289 m/s. The cannon is not anchored to the ground. It is mounted on a base— a large block of wood—which is sitting on a level roadway. If the road exerts a steady friction force of 430 N on the cannon’s sliding base, how much time does it take for the cannon to stop sliding after it fires the shell? 10/23/15 Oregon State University PH 211, Class #12 1 This graph shows the force that a tennis ball exerts on a wall as it bounces off of it. A motion detector indicates that the 60 g tennis ball has an impact speed of 32 m/s; it bounces back with the same speed. Find the maximum force exerted by the ball on the wall. Fball.wall (N) J t (ms) 0 10/23/15 2 4 6 Oregon State University PH 211, Class #12 2 A 50.0 kg girl runs across the dock at 6.0 m/s (horizontally) and leaps into a 35 kg boat, floating (initially) at rest, untethered. a. What is the boat’s speed just after the girl lands in it? b. Compare the impulses on each (the girl and the boat.) 10/23/15 Oregon State University PH 211, Class #12 3 How Long Does a Momentum “Exchange” Take? In every case we’ve ever observed where two objects, A and B, interact, their changes in linear momentum were equal in magnitude but opposite in direction: PB = –PA These individual changes in momentum PA, and PB, are called impulses. And each exchange of momentum involves a pair of impulses—equal in magnitude but opposite in direction. Question: The interaction that produced each pair of impulses lasted just a short while. Then the masses either separated or became one mass. But what about that “short while?” Was it the same amount of time for each mass? In other words, can object A stop touching object B before B stops touching A? 10/23/15 Oregon State University PH 211, Class #12 4 Conclusion: In an exchange of impulses, whatever A does to B, B does just the opposite to A—and in the same amount of time. But is time the only factor that determines the amount of P each object gets? Can a 1-second interaction give, say, 10 kg·m/s of impulse to object A (and of course, –10kg·m/s to B), but then another 1-second interaction could give 20 kg·m/s? Or 100? Of course. Clearly, the amount of P depends both on the duration and on the intensity of the interaction. The duration, t, is a scalar quantity (time) that is the same for both A and B. The “intensity,” therefore, must be a vector: equal in magnitude but acting oppositely in direction on each object, in order to produce the respective vector directions of the P for each object. This vector “intensity” of interaction is what we call a force, F. Thus: P = Ft 10/23/15 Oregon State University PH 211, Class #12 5 Now let’s get very specific with names: We name a force FAB when it is the action by object A on object B, over some time interval, t, which causes a change in B’s momentum, PB: FABt = PB And FBA is the action by object B on object A, over the time interval, t, which causes a change in A’s momentum, PA: FBAt = PA But we have already observed that (because momentum is conserved in this universe), PB = –PA In other words: FABt = –FBAt But matching impulses happen in the same t, so: FAB = –FBA Conclusion: Anytime there is a force, there are actually two forces—a matched pair: FAB = –FBA This is Newton’s Third Law. 10/23/15 Oregon State University PH 211, Class #12 6 Newton’s Third Law in words: “For every action, there is an equal but opposite reaction.” It describes the very nature of a force: A force must have two parties participating—with a force acting equally but oppositely on each party. Again, notice the units of force…. 10/23/15 Oregon State University PH 211, Class #12 7