Product Market Demand

advertisement

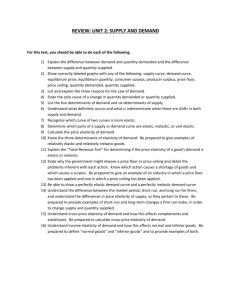

Chapter 4 – Product Market Demand This chapter examines the major causes of the Demand for a specific good – its own price, the prices of related goods, tastes, and consumer income. Also we distinguish between the qualitative (direction of change) versus the quantitative (elasticity) effects of a ceteris paribus change in each of these causes. Price and Quantity Demanded: Direction of Change Recall – the good’s own price (P) is a cause of quantity demanded of that good (Q). Qualitative Effect: P QD. Qualitative Effect – measures direction of change. Underlying Reason: Inverse Relationship Consumer maximizes utility subject to their budget constraint when MU1/P1 = MU2/P2 = … If P1, then consumer should rebalance by MU1 to make the ratio equal across goods again. Given diminishing Marginal Utility, this is done by having Q1. Own Price Elasticity of Demand Own Price Elasticity of Demand () – measures the magnitude of responsiveness of quantity demanded of a good to changes in its own price. In other words, the Quantitative Effect of a change in price on the quantity demanded of that good. Own Price Elasticity of Demand (): A Formula = |Percentage Change in QD| |Percentage Change in P| . Always has positive sign. Ratio of percentage changes instead of slope, makes it a unit-free measure. Price Inelastic Goods Price Inelastic Goods have < 1. These goods are unresponsive to changes in their own price. Example – suppose that if the Price of Milk increases by 10%, Quantity Demanded of Milk goes down by 3%. Then, for Milk, = |-3%|/|10%| = 0.3. Price Elastic Goods and Unitary Price Elasticity Price Elastic Goods have > 1. These goods are responsive to changes in their own price. Example – suppose that if the Price of Cars increase by 10%, Quantity Demanded of Cars goes down by 18%. Then, for Cars, = |-18%|/|10%| = 1.8. Unitary Price Elasticity: = 1. What Features Make Goods Price Inelastic or Elastic? Necessity versus Luxury Number and Quality of Available Substitutes Time Frame Price Relative to Wealth or Income Own Price Elasticity: The Demand Curve Price Inelastic goods are described with steep demand curves. The vertical demand curve is the extreme case of = 0. Price Elastic goods are described with flat demand curves. The horizontal demand curve is the extreme case of = . Own Price Elasticity and Equilibrium Consider an equilibrium, where Demand equals Supply. Supply shifts (rightward or leftward) change the equilibrium, accomplished by moving along the existing demand curve. Therefore the new equilibrium quantity can be compared to the original one by means of own price elasticity. Own Price Inelasticity and Total Revenue of Firms Total Revenue (TR) = (Price of Good)x(Quantity Sold), or TR = PxQ. This relationship implies that, in percentage change terms: (% Change in TR) = (% Change in P) + (% Change in Q). Own Price Elasticity and Increasing the Price Consider our two goods: milk ( = 0.3), and cars ( = 1.8). Suppose that supply shifts so that the price of each increases by 10%. % Change in TR of Milk = 10% + -3% = 7%. % Change in TR of Cars = 10% + -18% = -8%. Own Price Elasticity and Decreasing the Price Consider again our two goods: milk ( = 0.3), and cars ( = 1.8). Suppose supply shifts so that the price of each decreases by 10%. % Change in TR of Milk = -10% + 3% = -7%. % Change in TR of Cars = -10% + 18% = 8%. Application: What Goods Should Have a Sales Tax? Sales tax – tax on supply. Firms try to pass it on to consumers. Consider the contrast between a sales tax on a price inelastic good versus a sales tax on a price elastic good. What is the government’s goal – collect tax revenue or significantly reduce the quantity traded? Another Cause of Demand – Prices of Related Goods Consider, for example, the Demand for Coffee. Affected by prices of related goods in two different ways. -- PDONUTS QCOFFEE (Complements) -- PTEA QCOFFEE (Substitutes) Cross Price Elasticity Cross Price Elasticity (1x2) – measures the responsiveness of demand to changes in the prices of complements or substitutes. 1x2 = Percentage Change in Q2 Percentage Change in P1 . Interpreting Cross Price Elasticity 1x2 = Percentage Change in Q2 Percentage Change in P1 . Sign of 1x2 describes whether the related good is a complement (negative) or substitute (positive). Absolute Value of 1x2 describes the magnitude of response. |1x2| < 1 describes an inelastic response, while |1x2| > 1 describes an elastic response. Cross Price Elasticity: A Numerical Example Suppose that, for coffee: DONUTSxCOFFEE = -0.4 Negative sign Donuts are a complement. Absolute value < 1 Inelastic, or unresponsive. TEAxCOFFEE = 1.5 Positive sign Tea is a substitute. Absolute value > 1 Elastic, or responsive. Cross Price Elasticity and Dependence of Markets Consider the markets (i.e. Demand and Supply) for Gasoline, Cars, and Ethanol. Gasoline and Cars are Complements (PGAS QCARS ). Gasoline and Ethanol are Substitutes (PGAS QETHANOL ). Cross Price Elasticity and Dependence of Markets Suppose the government decides to put a substantial sales tax on gasoline (or another supply disruption). Decreases supply of gasoline, described by shifting supply curve for gas leftward P*GAS, Q*GAS. Cross Price Elasticity and Dependence of Markets The move also has effects in the markets for cars and ethanol. Decreases demand for cars, described by shifting the demand curve for cars leftward P*CARS , Q*CARS. Increases demand for ethanol, described by shifting the demand curve for ethanol rightward P*ETHANOL, Q*ETHANOL . Cross Price Elasticity – describes size of shifts for cars and electricity. Another Cause of Demand – Consumer Income The Demand for most goods is affected by changes in the consumer’s income (I). -- I Q (Normal Goods) -- I Q (Inferior Goods) Income Elasticity Income Elasticity (I) – measures the responsiveness of demand to changes in consumer income. I = Percentage Change in QD Percentage Change in I . Interpreting Income Elasticity I = Percentage Change in QD Percentage Change in I . Sign of I describes whether the good is a normal good (positive) or inferior good (negative). Absolute Value of I describes the magnitude of response. |I| < 1 describes an inelastic response, while |I| > 1 describes an elastic response. Income Elasticity: A Numerical Example Suppose that: For Tuna Helper, I = -1.4. Negative sign inferior good. Absolute value > 1 Elastic, or responsive. For Apples, I = 0.5. Positive sign normal good. Absolute value < 1 Inelastic, or unresponsive. Income Changes: Graphical Description Since income is “another cause” of demand, changes in income are described as shifts of the demand curve. Since it shifts the Demand curve, changes in consumer income affect P* and Q* as well. Income Changes: Graphical Description For normal goods (I > 0), I QD. Therefore, one describes an increase in income as a rightward shift in the demand curve. For inferior goods (I < 0), I QD . Therefore, one describes an increase in income as a leftward shift in the demand curve. Absolute value of income elasticity describes size of shift. Individual Versus Market Demand The Market Demand for any good is obtained by summing up the individual demands for all the consumers for this good. Example – consider the demand for apples. Suppose the demanders consist of two people, me and you. Demand for Apples Price ($) 0.20 0.25 0.30 0.35 0.40 0.45 Me + You 25 8 23 7 21 6 19 5 17 4 15 3 = Market 33 30 27 24 21 18 Causes: Market Demand For a Good Price of Good Price of Related Goods (Substitutes or Complements) Consumer Income (Normal or Inferior Good) Tastes Number of buyers in the market (Market Demand only) Demographics and Market Demand for Goods Changing population needs and preferences lead to changes in the number of participants. Example – aging of baby boomers. Decreases in market demand (shifts leftward) for fast food, adult soccer leagues, starter homes. Increases in market demand (shifts rightward) for fresh fruits, walking sneakers, retirement condos.