kant october 28 - contest of the faculties, etc.

0. Attendance

1. Questions from last lecture/tutorial

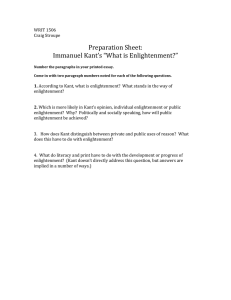

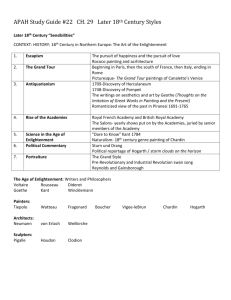

2a. What is enlightenment

The problem: lazy cowards don’t use their understanding.

The solution: allow for the public use of freedom (serving the machine, versus writing as a scholar to an educated audience)

“in so far as this or that individual who acts as part of the machine also considers himself as a member of a complete commonwealth or even of cosmopolitan society, and thence as a man of learning who may through his writings address a public in the truest sense of the word, he may indeed argue without harming the affairs in which he is employed for some of the time in a passive capacity” (56)

It would be a “crime against human nature, whose original destiny lies” in the progress of enlightenment for one age to “enter into an alliance on oath to put the next age in a position where it would be impossible for it to extend and correct its knowledge, particularly on such important matters” as religion (57). Enlightenment belongs to the “sacred rights of mankind” (58)

For Kant, “freedom [of inquiry into religious dogma] may exist without in the least jeopardising public concord and the unity of the commonwealth” (59).

Moreover, an enlightened head of state would recognize that there “is no danger even to his legislation if he allows his subjects to make public use of their own reason and to put before the public their thoughts on better ways of drawing up laws, even if this entails forthright criticism of the current legislation” (59).

Question: What would Rousseau say about the previous point, on the basis of his discussion of the Legislator and Civil Religion?

Question: What did Aristotle say in the Politics about the critique of the laws

(read the passage)? Who is right, Aristotle or Kant? Why?

Aristotle” (Book 2 chpt 7): “Hippodamus enacted that those who discovered anything for the good of the state should be honored…

It has been doubted whether it is or is not expedient to make any changes in the laws of a country, even if another law be better. Now, if an changes are inexpedient, we can hardly assent to the proposal of Hippodamus; for, under pretense of doing a public service, a man may introduce measures which are really destructive to the laws or to the constitution. But, since we have touched upon this subject, perhaps we had better go a little into detail, for, as I was saying, there is a difference of opinion, and it may sometimes seem desirable to make changes. Such changes in the other arts and sciences have certainly been beneficial; medicine, for example, and gymnastic, and every other art and craft have departed from traditional usage. And, if politics be an art, change must be necessary in this as in any other art. That improvement has occurred is shown by the fact that old customs are exceedingly simple and barbarous. For the ancient Hellenes went

about armed and bought their brides of each other. The remains of ancient laws which have come down to us are quite absurd; for example, at Cumae there is a law about murder, to the effect that if the accuser produce a certain number of witnesses from among his own kinsmen, the accused shall be held guilty. Again, men in general desire the good, and not merely what their fathers had. But the primeval inhabitants, whether they were born of the earth or were the survivors of some destruction, may be supposed to have been no better than ordinary or even foolish people among ourselves (such is certainly the tradition concerning the earth-born men); and it would be ridiculous to rest contented with their notions. Even when laws have been written down, they ought not always to remain unaltered. As in other sciences, so in politics, it is impossible that all things should be precisely set down in writing; for enactments must be universal, but actions are concerned with particulars.

Hence we infer that sometimes and in certain cases laws may be changed; but when we look at the matter from another point of view, great caution would seem to be required. For the habit of lightly changing the laws is an evil, and, when the advantage is small, some errors both of lawgivers and rulers had better be left; the citizen will not gain so much by making the change as he will lose by the habit of disobedience. The analogy of the arts is false; a change in a law is a very different thing from a change in an art. For the law has no power to command obedience except that of habit, which can only be given by time, so that a readiness to change from old to new laws enfeebles the power of the law. Even if we admit that the laws are to be changed, are they all to be changed, and in every state? And are they to be changed by anybody who likes, or only by certain persons?”

Question: Should scholars be allowed to call into question other fundamental beliefs in the name of enlightenment? Should they be allowed in the name of enlightenment to call into question the Constitution, even when it is secular?

Why or why not (on Kant’s view)?

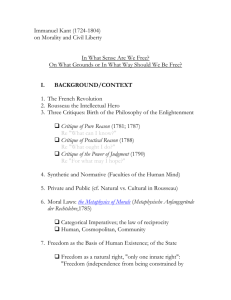

2b. The contest of the faculies

On individuals, aggregates, and our common humanity (1)

A history of the future is possible “if the prophet himself occasions and produces the events he predicts” (2)

Three conceptions of human history, cannot be resolved on the basis of experience (since you never know what the next member of the sequence will be): terroristic (“continually regressing”), eudaemonistic (“continually progressing”), abderistic (at a standstill, sometimes more, sometimes less)

(3)

On terroristic: “it seems the day of judgment is at hand, and the pious zealot already reams of the rebirth of everything and of a world created anew after the present world has been destroyed by fire” (3a)

Abderitism: libs->cons->libs->cons: same old, same old (you decide which is pushing the stone uphill and which is letting it role back down)

Free will is no basis for prediction (4) UNLESS we take an absolute perspective (“what nature intends for us,” as he talked about it in the Idea for a Universal History)

There is a conditional at the end of 4. Does Kant think that “man’s natural endowments consist of a mixture of evil and goodness in unknown proportions,” or does he think that “it [is] possible to credit human beings with even a limited will of innate and unvarying goodness”? Can you tell from this essay? Is the French Revolution proof of a will of innate and unvarying goodness?

The French Revolution is an event proving free causality in the service of legal improvement (5). It is a “historical sign”

What makes it a suitable sign of mankind’s tendency to improve? Kant says that it is the public reaction to the drama. The public “openly expresses universal yet disinterested sympathy for one set of protagonists against their adversaries, even at the risk that their partiality could be of great disadvantage to themselves”.

Kant is arguing that the universal sympathy of the onlookers to the revolution in the face of the danger of being sympathetic toward it is proof of humanity’s “moral disposition.” Moreover, this sympathy “cannot therefore have been caused by anything other than a moral disposition within the human race” (6)

The disposition consists in the right to people’s to self-legislate and their doing so in order to decrease the brutality and frequency of wars (6)

The issue of memory and whether it can be wiped out in human experience

(Plato’s Laws, natural catastrophes, Machiavelli, etc.) (7)

“Popular Enlightenment is the public instruction of the people upon their duties and rights towards the state to which they belong” (8): does this conflict with the definition of enlightenment in the other essay? Can duties and rights toward the state be called into question be the scholars? In the footnote to the last sentence of para. 9 he says that it is “punishable to incite the people to do away with the existing constitution.”

Feasibility: “It is a pleasant dream to hope that a political product of the sort we here have in mind will one day be brought to perfection, at however remote a date. But it is not merely conceivable that we can continually approach such a state; so long as it can be reconciled with the moral law, it is also the duty of the head of state (not of the citizens) to do so” (9, footnote)

Note: not man’s moral capacity, but the actualization of morality in law

(right) is the domain of progress (9)

3. The issue of foundationalism: from G. to R. (and beyond)

Post-foundationalism, optimistic (Rorty, e.g.), pessimistic (“German nihilism”) – do our moral intuitions require a basis in reason, nature, soul,

God, etc. Is such a basis available?