Articles for Poetry 2013 Juniors

advertisement

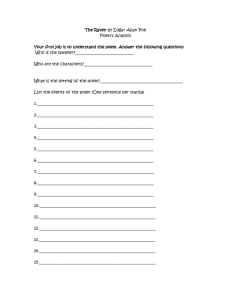

Articles for Poetry 2013 Juniors http://www.shmoop.com/thanatopsis/ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hGvX15W5dE4 Thanatopsis by William Cullen Bryant THANATOPSIS INTRODUCTION In A Nutshell Do you ever find yourself thinking about death? Have you ever felt your spine tingle when you walked past a graveyard, just thinking about all those bodies lying in the ground? Those are exactly the kinds of thoughts that William Cullen Bryant had when he wrote "Thanatopsis." Bryant was a young guy at the time he wrote this poem, maybe as young as 17. He was having dark thoughts, because, well, that’s what poetry-obsessed teenagers do (trust us, we here at Shmoop have some experience with this). Young William Bryant was a fan of a group of English writers called "The Graveyard Poets" who wrote all about death and decay. (Think of this as basically the 19thcentury version of listening to Cure albums all day.). It wasn’t all doom and gloom, though. Bryant was also getting to know the great Romantic poet William Wordsworth, whose love of nature had a pretty clear influence on this poem. That mix of calm nature poetry and dramatic thoughts of death helped to make "Thanatopsis" what it is. "Thanatopsis" was originally published without Bryant’s knowledge. His father found some of his son’s poems and sent them to a magazine called The North American Review without telling him about it. The first version of "Thanatopsis" appeared in that magazine in the September 1817 issue. The original poem was shorter, covering only what we now consider to be lines 17-66. The poem was a hit, and it was republished, with an added introduction and conclusion, in Bryant’s Poems, which came out in 1821. Bryant wrote more poems (and had a long career as a newspaper editor), but this early, relatively short poem will always be remembered as his masterpiece. WHY SHOULD I CARE? We hate to break it to you, dear Shmooper, but we have some bad news: you are going to die. Hey, don't get mad at us. We're just passing on the message fromWilliam Cullen Bryant. He really wants you to know that your days are limited. His poem "Thanatopsis" is all about death –your death. (OK, fine, ours too.) You do care about your death, don't you? The good news is that Bryant doesn't think you should be afraid of dying. It's worth reading "Thanatopsis" to soothe your fears. And lots of other artists agree with Bryant. So while you're at it, be sure to check out these songs, poems, and books: "(Don't Fear) the Reaper" by Blue Oyster Cult (listen or read the lyrics) "Dust In the Wind" by Kansas (listen or read the lyrics) "When Death Comes" by Mary Oliver "Because I could not stop for Death" by Emily Dickinson "The Graveyard Book" by Neil Gaiman THANATOPSIS SUMMARY "Thanatopsis" starts by talking about nature's ability to make us feel better. The speaker tells us that nature can make pain less painful. It can even lighten our dark thoughts about death. He tells us that, when we start to worry about death, we should go outside and listen to the voice of nature. That voice reminds us that we will indeed vanish when we die and mix back into the earth. The voice of nature also tells us that when we die, we won’t be alone. Every person who has ever lived is in the ground ("the great tomb of man") and everyone who is alive will be soon dead and in the ground too. This idea is meant to be comforting, and the poem ends by telling us to think of death like a happy, dream-filled sleep. Tide Rises http://suture.deviantart.com/art/The-Tide-Rises-Analysis-1074777 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0beexJBCMn4 The Tide Rises The Tide Falls General Theme---------------------------------I believe that it is the general consensus that this poem is about the immutable progression of time, as well as death, but not as something to be feared, simply as something that happens. One could take this several ways, but for our purposes here I'll just outline a couple of them. First of all, one could take the "traveler" in the poem as simply one man's life. In this case, the man would be on the verge of death (later we will find out why that is so). His "travels" would of course represent his life symbolically, and his disappearance would signify his death/burial. We could imply through this that Longfellow could perhaps be making a comment upon how life is always moving forward, and although death is a part of that cycle it is not something to be feared but accepted. Contrastingly, however, we could take the "traveler" to be life in general. The comments made by Longfellow would not differ much but the scope of his vision would. In this case we would see "life" as it traverses through ever-present struggles, and how time continues on unabated without the slightest notice of these struggles. To clarify, we could imply that Longfellow was simply inferring that the troubles in life are fleeting, and cannot last. It would also mean that in overcoming these struggles we are past them and never have to face them again. Anyway, on to the analysis we go... ----------------------------------Form-- ------------------------------------Yes, the "F" word. Please don't be frightened off though, I am just going to discuss a few minor details and how they add to the piece, not bore you with poetic theory. First, obviously, is the rhyme scheme. You will notice that it is written in rhyming couplets (two successive lines that rhyme) with a refrain that is repeated at the end of each stanza. The couplets serve a two-fold purpose. First, the poet uses them to force the reader into a certain "flow" of reading the poem. It is impossible to read the poem and not have it affect the way you read it. Manipulation of the reader is the poet's first and foremost tool. By using this particular form he is able to string us along within each stanza, then slap us in the face with the theme at the end of each stanza, and there is very little that we can do otherwise, unless of course you quit reading. Secondly, the poet uses the couplets to tie together two lines thematically. You will notice that each couplet acts cohesively to deal with a proposed action/metaphor/description (1,2...3,4...6,7...etc.). The use of the couplet is just Longfellow's way of saying, "Hey! This is one idea, and the next two lines are a different idea." The refrain (the repeated linelines) is where he has embedded his theme. Basically, through this line he is saying “Time goes ever onward” (to paraphrase a bit). This is very important (Of course it is! It's the theme!) when you consider the other references to time that he makes, but we will get to that a bit later. You will notice that not only is the refrain held at the end of each stanza, but also it is the first line. Obviously, the poet wants to make his theme known from the "get go," as well as to add a bit of a motif (a recurring thematic element). However, this also serves to tie the end and the beginning into one tightly wrapped "package." He begins and ends with the theme while all the while we are unaware because we simply follow the flow of his words. Notice, if you will, the last word of lines 2, 7, and 12 (the second line of each stanza). Yes! Always the same word - "calls". One could chalk this up to coincidence, but as you will see with all accomplished poets there is no such thing as coincidence in poetry. Everything has a reason to Longfellow. In this piece those line endings serve to point up the fact that time (represented by each line differently, but we will get into that later) is ever "calling". In effect it is an unavoidable end to which we are flowing. This use of a recurring word has a massive impact upon the rest of the poem. How? You ask? (I'm glad you did...heh...) Logically, if those lines end the same than the lines of their corresponding couplets must also rhyme. I know from experience that this is a VERY difficult task to accomplish, especially as seamlessly as this. However, this unifies the poem even further. It is like braiding hair/rope/whatever; each twist ties the words more and more together, and by so doing creates a much stronger whole. That's probably enough with the form for you to get the general picture of the sheer level of difficulty involved in "word-smithing" this piece. -------------------Language Devices in Relation to Theme------------------This is the part that makes poetry so appealing. These are the petals to the rose of poetry. Yes, I am talking about simile, metaphor, allusion, symbolism, alliteration, assonance, consonance, and all the other myriad of technical devices used in poetry. Imagine these as the chrome on your brand new Corvette, or perhaps as the lace upon a brand new dress, although these devices are more important to poetry than those analogies would imply. Let me ask you to notice something, within each stanza of "The Tide Rises, The Tide Falls," there is represented a certain time of day. This is a rather obscure symbol, but because it is important to the theme we will start with it. The times of day represented are sunset, night, sunrise - respectively. The order in which they occur is very important. By placing them in this order Longfellow is implying that the passage of time is not something “evil” or “frightening,” but rather is a “hopeful” occurrence.... Well, at least he is implying there is hope, and we’ll leave it at that. You see if night for instance had been placed in the last stanza the poem would be far more ominous and disheartening. Next, along with our recurring word ("calling") we are faced with three different symbols - the curlew, the sea, and the hostler. These symbols are on the line with the recurring word, so logically that would lead us to believe that they represent the same thing, because they are tied together by the word "calling." If we follow the theory that "the traveler" is in fact one man's life then that would lead us to believe the thing that is "calling" is in fact death. Here is why. The dictionary says that curlews are brown, long legged, migratory birds related to sand pipers. Water birds, no doubt, so we can safely say that they probably eat things that wash up on the beach, or small fish and crustaceans. Imagine the buzzards circling a carcass, or just the fact that the birds would have to kill the small fish, it seems very likely that death is involved to some degree. The sea is erasing the footprints in the second stanza, so again we could imply that his life is being "erased" indicating an end or death. Finally we find the hostler (a person appointed to take care of horses or mules) and we are faced with the figure from Greek myth, Charon, who ferried souls over the river Styx into the underworld (ok...that may be a stretch). One could simply envision carriage come to take some dignitary to any random event, and through the next few lines we find that the traveler is no longer there.... So what end do we reach? Yep. Death. But through it all we see that life is going on still, just as it has before his birth, during his life, and just as it will after his death. Death is painful, but there is comfort in realizing that the sun will rise again upon the morrow. If, however, we follow the second theory, and the traveler represents life, then the symbols would differ slightly. We would see that the curlew represents the way we are forced to "crack our way" through life with our bear beak (What? You don't have a beak?) as we struggle for our meager meal. We would see that the sea represents time healing all those past transgressions as well as causing memories to be erased of both good and bad happenings within our life. And finally we would see that the hostler represents the future "calling" us to new experiences. All the while we live, we die, we birth, we move, we speak, and still things keep on moving. The Raven http://www.shmoop.com/the-raven/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g13lshybdqo The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe THE RAVEN INTRODUCTION In A Nutshell You know what’s a good way to think about “The Raven”? As a one-hit wonder—or rather, the biggest one-hit wonderiest wonder that ever wondered. Because, really, that’s exactly what it was back in the day of its publication. Edgar Allan Poe was already a working writer, trying to make a living by the pen in the U.S. back in the days before intellectual property was protected by law. Back then, it wasn't easy making the big bucks off the written word, because without copyright laws, publishers could just pirate some stuff from England for free rather than actually pay money to some American author to, you know, author. So as a starving artist, Poe earned just enough to survive on, writing some poems, spooky stories, and some super sharp and stabby criticism of other people’s work. Nothing too fancy. Then, wham-bam, in 1845, he published “The Raven” in two newspapers at once. It's a lyrical narrative poem about a student who goes crazy questioning a bird about his lost love Lenore and only ever getting one answer: “Nevermore.” And the thing took off like wildfire (we guess people like their birds taciturn). In the course of a few months, it was published over and over again, in newspaper after newspaper. By the end of the century, it would be translated into almost every European language. And in between? It became the most popular and famous lyrical poem from America. Not only that, but its crazy popularity spawned a whole cottage industry of “The Raven” merchandise. Well, okay, not merchandise per se. Sadly for Poe, who never made much money from the poem, there weren't really any hats or t-shirts or key chains—just reams and reams of books and myths and lore about the poem, most if which was written after Poe’s death in 1849. This flood was kicked off by Poe’s longtime frenemy Rufus Griswold, who used Poe’s death as an occasion for his signature jerk move: writing an obituary that was actually a series of attacks, accusing Poe of being immoral, crazy, and depressive. Somehow, though, this takedown was totally reframed by other folks almost immediately, and things ended up turning out okay for the late Poe. Because you know what “immoral, crazy, and depressive” sounds like? That’s right, it sounds just like all the other moody heroes of the Romantic Movement: Byron,Keats, and Shelley. Throw in the word “genius”, like other Poe obituaries did, and you’ve got yourself a bona fide star. To this day “The Raven” is surrounded by legend and controversy. Was Poe a plagiarist? Did he steal the raven from Dickens’s “Barnaby Rudge” and his meter and rhyme scheme from Elizabeth Barrett Browning? Did he write it alone? With the help of some other poet? With the help of random strangers at a bar? There are endless criticisms answering all of these questions and generating still others. So will there ever be complete factual account of "The Raven"? Say it with us now, “Nevermore.” WHY SHOULD I CARE? So, we know this poem is famous and important and everything, but more than that, we think it's just a lot of fun. It's spooky and a little spine-tingling, like a good horror movie. It's fun to read – we almost can't stop ourselves from reciting it out loud. We recommend you try it and see how satisfying these lines are when they roll off the tongue. Poe really knows how to create a mood, to make his reader feel the shadows, the creepy noises in the room, the croak of the bird. This is a poem that pulls you into a moment. Like anything that scares you in a fun way, this is all about making you feel like you are experiencing the story while you read it. It's kind of cool to think that people have been excited by stories like this for hundreds of years. Folks in the 19th century read Poe for the same reasons we read Stephen King: that creepy thrill in reading about scary things happening to other people. When you read a story about someone slowly losing his mind, you might be horrified, but it's also pretty hard to put it down. So, we don't think you'll be able to resist Poe. THE RAVEN SUMMARY It's late at night, and late in the year (after midnight on a December evening, to be precise). A man is sitting in his room, half reading, half falling asleep, and trying to forget his lost love, Lenore. Suddenly, he hears someone (or something) knocking at the door. He calls out, apologizing to the "visitor" he imagines must be outside. Then he opens the door and finds…nothing. This freaks him out a little, and he reassures himself that it is just the wind against the window. So he goes and opens the window, and in flies (you guessed it) a raven. The Raven settles in on a statue above the door, and for some reason, our speaker's first instinct is to talk to it. He asks for its name, just like you usually do with strange birds that fly into your house, right? Amazingly enough, though, the Raven answers back, with a single word: "Nevermore." Understandably surprised, the man asks more questions. The bird's vocabulary turns out to be pretty limited, though; all it says is "Nevermore." Our narrator catches on to this rather slowly and asks more and more questions, which get more painful and personal. The Raven, though, doesn't change his story, and the poor speaker starts to lose his sanity. Song of Myself http://www.shmoop.com/song-of-myself/summary.html http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cm-n9wFZMiE Song of Myself by Walt Whitman Cite This Page Home Poetry Song of Myself Summary INTRO THE POEM SUMMARY Note Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 Section 4 Section 5 Section 6 Section 7 Section 8 Section 9 Section 10 Section 11 Section 12 Section 13 Section 14 Section 15 Section 16 Section 17 Section 18 Section 19 Section 20 Section 21 Section 22 Section 23 Section 24 Section 25 Section 26 Section 27 Section 28 Section 29 Section 30 Section 31 Section 32 Section 33 Section 34 Section 35 Section 36 Section 37 Section 38 Section 39 Section 40 Section 41 Section 42 Section 43 Section 44 Section 45 Section 46 Section 47 Section 48 Section 49 Section 50 Section 51 Section 52 ANALYSIS THEMES QUOTES STUDY QUESTIONS BEST OF THE WEB HOW TO READ A POEM LIT GLOSSARY SONG OF MYSELF SUMMARY BACK NEXT There's no way to fully summarize this poem, because there is so much in the poem. Seriously – Walt Whitman changes topics almost every other line. But there are a few main ideas you should know about before starting. Let's start off with the basics: our speaker, who is actually named Walt Whitman, declares that he's going to celebrate himself in this poem. He then invites his soul to hang out and stare at a blade of grass. It's the party of the year. He explains how much he loves the world, especially nature, and how everything fits together just as it should. Everything is good to him, and nothing is bad that doesn't contribute to some larger good. Nature has patterns that fit together like a well-built house. The speaker divides his personality into at least three parts: 1. The "I' that involves itself in everyday stuff like politics, fashion, and what he's going to eat; 2. The "Me Myself" that stands apart from the "I" and observes the world with an amused smile; and 3. The "Soul" that represents his deepest and most universal essence. Whitman thinks it's important for people to learn through experience and not through books or teachers. (If you like this idea, check out his short and sweet poem called "When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer" http://www.shmoop.com/learnd-astronomer/; you'll be a fan.) A child asks him what the grass is, and he doesn't have an answer, which gets him thinking about all kinds of things, but especially about all the people buried in the earth who came before him. He identifies with everyone and everything in the universe, including the dead. He imagines that he's a bunch of different people, from a woman staring at naked bathers to a crewman on a ship during a naval battle. His soul takes him on a journey around the world and all over America. Whitman tells us a bit about what he believes and what he's opposed to. Let's start with what he's opposed to: People who think they preach the truth, like the clergy Feelings of guilt and shame about the body Self-righteous judgments On the flip side, Whitman believes that: Everyone is equal, including slaves Truth is everywhere, but unspeakable An invisible connection and understanding exists between all people and things Death is a fortunate thing and not something to fear People would be better off if they had faith in the order of nature (and death is part of this order) He's awesome, and thinks people should take pride in themselves At the end of the poem, he says that he's going to give his body back to nature and to continue his great journey. He'll be hanging out ahead on the road, waiting for us to catch up with him. Because I could not stop for death http://www.cummingsstudyguides.net/Guides2/Dickinson.html http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DDOfwqqtGE8 Because I Could Not Stop for Death A Poem by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) A Study Guide cummings@cummingsstudyguides.net Cummings Guides Home Type of Work Commentary and Theme Characters Text and Notes Meter End Rhyme Internal Rhyme Symbols Figures of Speech Critic Praises Poem Question, Writing Topics Biography ... Study Guide Prepared by Michael J. Cummings...© 2003 Revised in 2011...© . Type of Work “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” is a lyric poem on the theme of death. The contains six stanzas, each with four lines. A four-line stanza is called a quatrain. The poem was first published in 1890 in Poems, Series 1, a collection of Miss Dickinson's poems that was edited by two of her friends, Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. The editors titled the poem "Chariot." Commentary and Theme “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” reveals Emily Dickinson’s calm acceptance of death. It is surprising that she presents the experience as being no more frightening than receiving a gentleman caller—in this case, her fiancé (Death personified). The journey to the grave begins in Stanza 1, when Death comes calling in a carriage in which Immortality is also a passenger. As the trip continues in Stanza 2, the carriage trundles along at an easy, unhurried pace, perhaps suggesting that death has arrived in the form of a disease or debility that takes its time to kill. Then, in Stanza 3, the author appears to review the stages of her life: childhood (the recess scene), maturity (the ripe, hence, “gazing” grain), and the descent into death (the setting sun)–as she passes to the other side. There, she experiences a chill because she is not warmly dressed. In fact, her garments are more appropriate for a wedding, representing a new beginning, than for a funeral, representing an end. Her description of the grave as her “house” indicates how comfortable she feels about death. There, after centuries pass, so pleasant is her new life that time seems to stand still, feeling “shorter than a Day.” The overall theme of the poem seems to be that death is not to be feared since it is a natural part of the endless cycle of nature. Her view of death may also reflect her personality and religious beliefs. On the one hand, as a spinster, she was somewhat reclusive and introspective, tending to dwell on loneliness and death. On the other hand, as a Christian and a Bible reader, she was optimistic about her ultimate fate and appeared to see death as a friend. Characters Speaker: A woman who speaks from the grave. She says she calmly accepted death. In fact, she seemed to welcome death as a suitor whom she planned to "marry." Death: Suitor who called for the narrator to escort her to eternity. Immortality: A passenger in the carriage. Children: Boys and girls at play in a schoolyard. They symbolize childhood as a stage of life. Text and Notes Because I could not stop for Death, He kindly stopped for me; The carriage held but just ourselves And Immortality. We slowly drove, he knew no haste, And I had put away My labor, and my leisure too, For his civility. We passed the school, where children strove At recess, in the ring; We passed the fields of gazing grain, We passed the setting sun. Or rather, he passed us; The dews grew quivering and chill, For only gossamer my gown,1 My tippet2 only tulle.3 We paused before a house4 that seemed A swelling of the ground; The roof was scarcely visible, The cornice5 but a mound. Since then 'tis centuries,6 and yet each Feels shorter than the day I first surmised the horses' heads Were toward eternity. Notes 1...gossamer my gown: Thin wedding dress for the speaker's marriage to Death. 2...tippet: Scarf for neck or shoulders. 3...tulle: Netting. 4...house: Speaker's tomb. 5...cornice: Horizontal molding along the top of a wall. 6...Since . . . centuries: The length of time she has been in the tomb. . Meter In each stanza, the first line has eight syllables (four feet); the second, six syllables (three feet); the third, eight syllables (four feet); and the fourth, six syllables (three feet). The meter alternates between iambic tetrameter (lines with eight syllables, or four feet) and iambic trimeter (lines with six syllables, or three feet). In iambic meter, the feet (pairs of syllables) contain an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable. (For detailed information on meter, click here.) The following example demonstrates the metric scheme. .......1..................2...............3....................4 Be CAUSE..|..I COULD..|..not STOP..|..for DEATH, ......1..................2.................3 He KIND..|..ly STOPPED..|..for ME; ........1.................2.................3...................4 The CARR..|..iage HELD..|..but JUST..|..our SELVES ....1..............2............3 And IM..|..mor TAL..|..i TY. End Rhyme .......The second and fourth lines of stanzas 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 rhyme. However, some of the lines contain only close rhymes or eye rhymes. In the third stanza, there is no end rhyme, but ring (line 2) rhymes with the penultimate words in lines 3 and 4. Internal Rhyme .......Dickinson also occasionally uses internal rhyme, as in the following lines: The carriage held but just ourselves (line 3) We slowly drove, he knew no haste (line 5) We passed the fields of gazing grain (line 11) The dews grew quivering and chill (line 14) Symbols .......In the fourth stanza, the school symbolizes the morning of life; the grain, the midday of life and the working years; the setting sun, the evening of life and the death of life. Figures of Speech .......Following are examples of figures of speech in the poem. (For definitions of figures of speech, click here.) Alliteration Because I could not stop for Death (line 1) he knew no haste (line 5) My labor, and my leisure too (line 7) At recess, in the ring gazing grain (line 11) setting sun (line 12) For only gossamer my gown (line 15) My tippet only tulle (line 16) toward eternity (line 24) Anaphora We passed the school, where children strove At recess, in the ring; We passed the fields of gazing grain, We passed the setting sun. (lines 9-12) Paradox Since then 'tis centuries, and yet each Feels shorter than the day I first surmised the horses' heads (lines 21-23) Personification We passed the setting sun. Or rather, he passed us (lines 12-13) Comparison of the sun to a person Death is personified throughout the poem I heard a fly buzz when I died http://www.shmoop.com/i-heard-a-fly-buzz-when-i-died/analysis.html file on E I heard a Fly buzz – when I died – by Emily Dickinson I HEARD A FLY BUZZ – WHEN I DIED – ANALYSIS Symbols, Imagery, Wordplay Welcome to the land of symbols, imagery, and wordplay. Before you travel any further, please know that there may be some thorny academic terminology ahead. Never fear, Shmoop is here. Check out our... Form and Meter When you read this poem through, did you notice a certain smooth, even feeling to the lines? That’s because this is actually a really regular, rhythmic poem in some ways…but not in ever... Speaker Since this speaker is talking about the moment when she (or he) died, it seems safe to assume that she is some kind of ghost or spirit. We think that the way she talks really drives this home. Do y... Setting So, Ms. Dickinson isn’t a lot of help with the setting. She tells us that we’re in a room, but not a lot else. OK, that’s not really fair. We know that we are looking at a deathbe... Sound Check We think this poem’s sound is ruled by those little dashes. We get bursts of sound, then a pause, then another burst. It’s like listening to someone flipping through stations on a radio... What's Up With the Title? Well, this poem doesn’t actually have a title. Dickinson didn’t publish her poems in her lifetime, and they were found in a drawer after her death, bound up in little handwritten books.... Calling Card Emily Dickinson always sprinkles those funny dashes throughout her poems. As long as the editor left them in, it’s a pretty surefire way to tell it’s one of hers. Her poems also tend to... Tough-O-Meter This shouldn’t be too tough a climb. The main scene is pretty easy to get your head around. Keep an eye out, though, because some of these images are a little mysterious, and might mean more... Brain Snacks Sex Rating What with the fly and all the dying and the crying, we think this poem is way unsexy.